Cassander: The Self-Made King of (What Was Left Of) Macedon

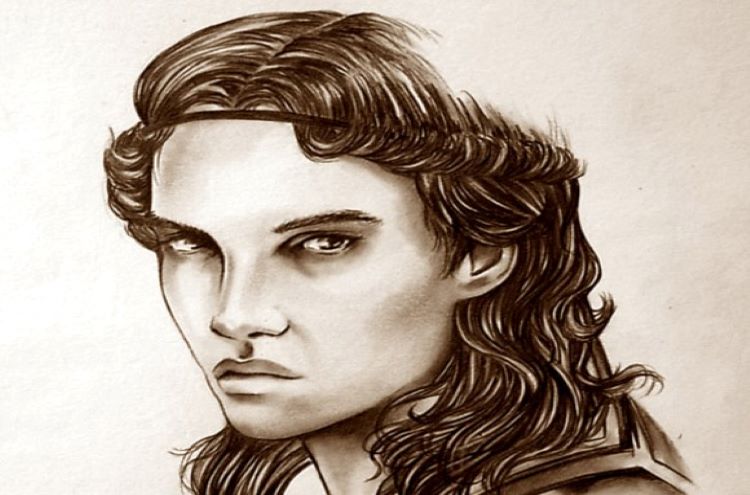

Cassander was born in 355 B.C.E. as the son of Antipater. He was a member of the so-called Iolaid House, an obscure family of high political prominence in Macedon. The house drew its privileges and identity from one Iolaus who had served as archon for Perdiccas II (r. 448-413) at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. From then on, the Iolaids seems to have had hereditary claims to a regency position in Macedon. Cassander’s father Antipater served as a regent both during the reign of Philip II and Alexander III “the Great”, governing affairs while those kings were away. A brother of Cassander was also called Iolaus.

Fighting a Wasting Disease

Cassander suffered from a chronic illness that Eusebius calls “a wasting disease”, likely tuberculosis. This hindered Cassander’s performances in martial arts since his youth. Especially his lack of success in hunting, an important initiation ritual among the Macedonian men, had him alienated from the rest of the would-be generals. Because of his vulnerable physical condition, Cassander was classified as unfit for military service and the prestige that came with it. Thus, Cassander stayed home in Macedon while his peers of the same age such as Perdiccas, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Leonnatus joined Alexander in his expedition and made a name for themselves.

The alienation of Cassander from the expedition had an impact on his perception of the ruling family. Moreover, at home, he had to endure constant complaints of Olympias to Alexander from his father. He naturally grew hate towards Olympias and, at first, an unconscious grudge against Alexander himself.

An Uneasy Stay in Babylon

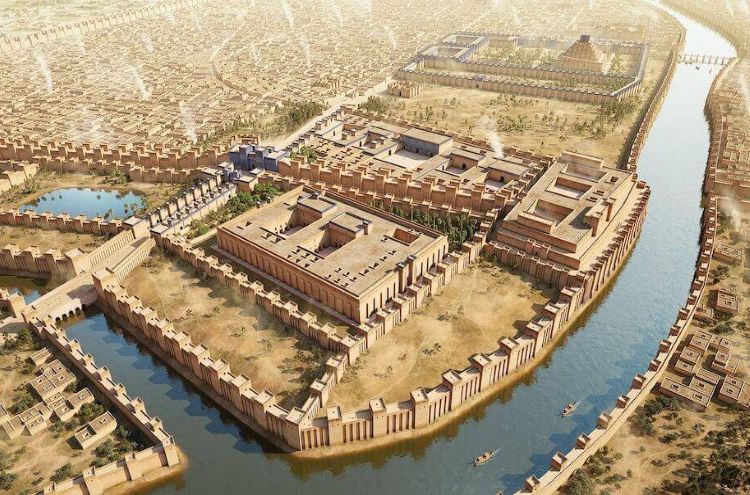

Olympias’ quarrel with Cassander’s father reached the boiling point in 324 when Alexander had returned to Babylon. The king, now siding with his mother in the quarrel, ordered Antipater to come from Macedon into Babylon where he was to meet him. Antipater, believing the invitation to result in a fatal punishment for him sent, on his behalf, his son Cassander.

Cassander showed up in Babylon to make a plea on his father’s behalf. Indeed, when Cassander came forwards to face Alexander he noticed several Persians prostrating (bowing down in a sign of respect) to Alexander. Unaccustomed to the practice, common among the Persians, Cassander began laughing, a genuine but inappropriate reaction. This so angered Alexander that he clutched Cass “fiercely by the hair with both hands [and] dashed his head against the wall” (Plut, Alexander. LXXIV). This so much humiliated and trembled Cassander, that, even later in life, he would almost faint at the sight of Alexander’s statues.

Cassander continued his stay in Babylon, refuting charges against his father, though his audiences with Alexander ended up in a fracas. In June 323 Alexander, the man who had conquered most of the known world, succumbed to malaria at the age of 33. Cassander and Antipater were now free from accusations whereas the empire was up for grabs. Back in Europe, Olympias believed that the demise of her son was the result of Antipater and Cassander’s conspiracies. In fact, Cassander’s brother Iolaos had been Alexander’s chief cupbearer at the time; for Olympias, he had been the one administering a fatal poison to Alexander.

A Disappointing Testament

In February 319, Antipater succumbed to old age and poor health, soon after returning to Macedon from Triparaidesos. Antipater’s choice of successor was a seemingly strange one. Rather than picking his own son Cassander as his successor, he chose Polyperchon for that office. Thus, Polyperchon rose to the regency, gaining supreme command of the royal army and assuming guardianship of the joint kings. Cassander, according to his father’s own will, was only appointed a second in authority (chiliarch).

Cassander was clearly angered and disappointed with his father’s decision. As such, he was determined to make a run for the regency at the expense of Polyperchon. For the moment though, he had to move cautiously. Before getting his hands into an army, essential to challenge Polyperchon’s authority, Cassander could not declare any war on anyone.

For purposes of securing troops and allies, he sent envoys in secret to Ptolemy in Egypt. He sought to gain naval assistance from Ptolemaic bases in Phoenicia. Himself, Cassander crossed the Hellespont and arrived in Asia Minor. Here he met Antigonus and, after an audience with him, secured a precious force of 4,000 infantry and a fleet of 35 ships. With these forces, Antipater’s son set sail for Piraeus.

Despite Antigonus’ aid, Cassander was at a disadvantage compared to Polyperchon in terms of sheer numbers of supporting troops. Polyperchon had the command of the Macedonian home army numbering some 25,000 thousand troops. He also could deploy on a campaign about 65 war elephants.

Alliance between Cassander and Adea

However, Cassander could rely on greater popular support, especially across mainland Hellas, that he enjoyed compared to Polyperchon. Indeed, people across Macedon and Greece were accustomed to Cassander, physically present there at the time of Antipater’s regency. Meanwhile, Polyperchon had spent the last fifteen years away, on a campaign in Asia with king Alexander. Thus, for the Macedonian and Greeks at home, Polyperchon represented disruption while Cassander represented the continuum. In the view of common folks, Polyperchon looked more like a challenger than a legitimate regent being challenged. This, combined with Polyperchon’s apparent lack of charisma, influenced many cities to rally themselves in support of Cassander.

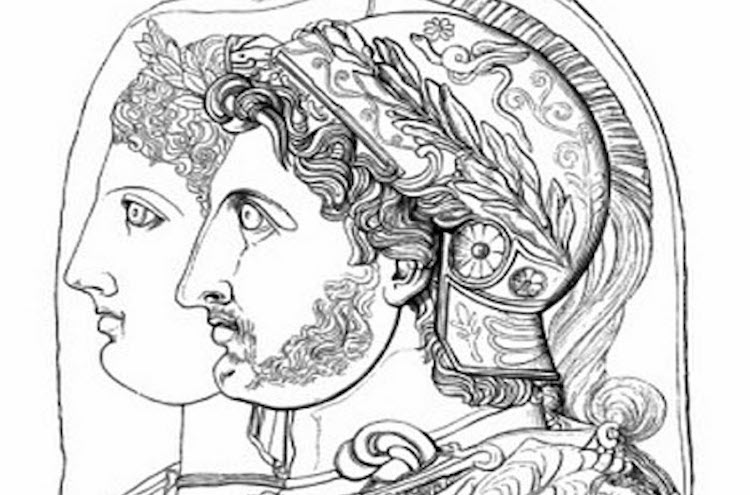

Cassander found another important ally in Adea/Eurydice, daughter of Amyntas IV and Cynane. The two had the opportunity to establish friendly ties with one another in between 320-319, both being at court in Pella. Moreover, in 321 Adea had become the only queen of Macedon by marrying the then king Philip Arrhidaeus (himself mentally handicapped). Because of Arrhidaeus’ condition, Adea could effectively use her husband to advance her own cause. In the conflict between Polyperchon (an ally of Olympias) and Cassander, she naturally chose the latter.

On his own Cassander could use Adea to earn the legitimacy his father had denied him. Thus, when Polyperchon left Macedon to fight Cassander, Adea, through a letter that bore the credentials of king Philip Arrhidaeus, proclaimed Cassander as regent. In other letters, she officially ordered Polyperchon to resign from the regency and Antigonus to recognize and support Cassander as the new, legitimate regent and viceroyal. In the summer of 317, Cassander went personally into the court of Philip and Adea for his public proclamation of the regency.

Cassander vs Polyperchon

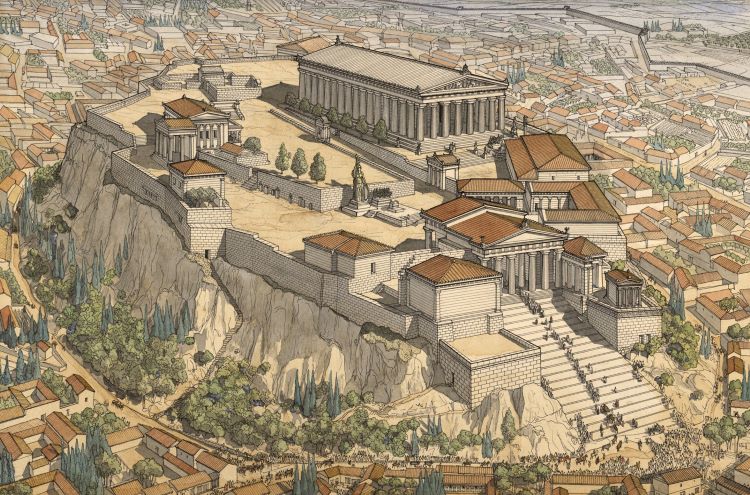

Cassander moved quickly to establish control of Athens and the nearby harbor of Piraeus, vital for marine-based warfare. He quickly turned Attica, Boeotia, and the cities across the Peloponnesus into his power bases. Specifically, he relied on cities garrisoned by commanders loyal to him. Such cities were Argos, Corinth, Megalopolis, and the fortress of Munychia at Athens. In fact, Cassander had replaced since before his revolt the phrourarchos of Munychia Menyllus with Nicanor, a man at that point loyal to Cassander alone. In fact, Nicanor did a good job by stalling the Athenians with promises of liberty while waiting for Cassander to dock with additional forces at Piraeus. Meanwhile, the veteran Damis, in charge of the garrison at Megalopolis also supported Cassander’s cause.

Polyperchon, aware of popular support for Cassander across mainland Hellas, tried a PR stunt to cut off this support. Accordingly, Polyperchon issued a decree which he promoted as proclaiming freedom and autonomy for all Greek cities. Yet, those receiving the decree took its message for what it really was: an instrument intended against Cassander alone with no real intention of freeing Greece. Nowhere is the poor formulation of this decree clearer than in the following clause: “Let all the Greeks pass a decree that no one shall change either in war or in public opposition to us, and that if anyone disobeys, he and his family shall be exiled and his goods shall be confiscated” (Diod. XVIII. LVI. I.)

Diplomatic Fight for Athens

Despite his poorly formulated decree, Polyperchon had reason to believe in turning Athens into his side. According to that same decree, Samos was granted to Athens and Athenians political exiles in time of Antipater restored and pardoned. Also, Olympias, allied with Polyperchon, came forwards through a letter ordering Cassander to remove his garrison from the city.

To prevent the Athenians from joining the cause of his enemies, Cassander smartly removed his garrison from Athens. However, simultaneously he installed a government that would support his cause led by the popular philosopher Demetrius of Phalerum. By appearing thus as a supporter of Athens’ long democratic and philosophical tradition, Cassander still retained control of Athens. Cassander would, later on, try the same move on Epirus and other regions, installing puppet governments to establish control.

Victories on Land and Sea

When Cassander was in Piraeus, Polyperchon with all his army moved into Attica from Phocis and besieged the harbor. Finding the city ready for the siege, the regent left a small force here to continue the besiegement under his son Alexander. He with most of the troops marched into Peloponnesus to capture Megalopolis.

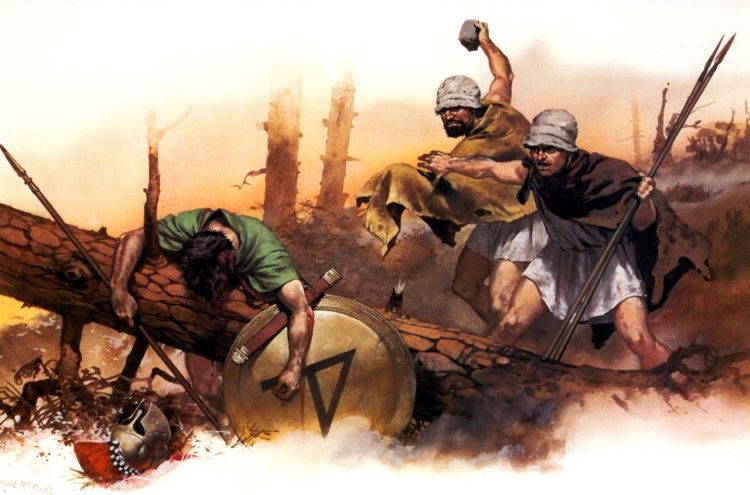

When Polyperchon arrived in Peloponnesus, Megalopolis was well-prepared for a siege. The city strongly supported the cause of Cassander. Fifteen thousand men under the leadership of the skilled veteran Damis not only held the city but also destroyed most of Polyperchon’s army. At about the same time, Cleitus, admiral of Polyperchon’s whole fleet, was crushed near the Hellespont by the combined navies of Nicanor and Antigonus.

After the success in Megalopolis and in the open sea, “most of the Greek cities deserted the kings and went over to Cassander” (XVIII.LXXIV.I).

Cassander vs Olympias

In the fall of 317, Olympias entered the fight for power. Supported by an army of Epirotes, a kingdom led by her nephew Aeacides, she advanced into Macedon. In the process, Alexander’s mother, still enjoying support among the Macedonians, executed king Philip IV Arrhidaeus and his wife Adea/Eurydice.

Cassander unleashed a blitzkrieg into Macedon quickly enclosing Olympias at Pydna. In early 316 Cassander took hold of Olympias stronghold. After a show trial, Cassander had Olympias executed. He also made sure to keep Roxana and her son Alexander IV were isolated at Amphipolis.

After the execution of Olympias and the surrender of Aristonous in Amphipolis, Cassander became the sole, semi-official ruler of Macedon. His rival Polyperchon remained in Aetolia and then in Peloponnesus but with such a small army that he could not pose any threat. To commemorate his victory and ensure his legacy, in mid-316, Cassander married Thessalonike, daughter of Philip II and Nikesipolis. A marriage with one of Philip’s offspring could only improve one’s legitimacy among the Macedonians.

A Missing Piece of Cassander’s “Marital Mosaic”?

However, a strange circumstance comes up when considering Cassander’s marriage with Thessalonike: it being only the first marriage of a Cassander then almost 40 old! Literal evidence gives no solution to this problem, but a piece of sole epigraphic evidence does. According to it, the existence of a princess named Cynane is testified, likely a younger sister of Adea/Eurydice, bearing the name of her mother. The same inscription testifies to a daughter of Cynane II that did not survive past infancy. An earlier marriage between the Cynane II of the inscription and Cassander solves the problem of Cassander’s late marriage. It also explains why Adea/Eurydice sided with Cassander since the beginning of his conflict with Polyperchon.

If we are to believe an earlier marriage between Cassander and Cynane II, sister of Adea/Eurydice, this means that Cassander was in a stronger position by 319 than previously believed. Cassander must have married Cynane II sometime during that year after Adea/Eurydice had already ascended to queenship two years ago by marrying Philip Arrhidaeus. This marriage gave Cassander a daughter, the Adea II commemorated in the inscription, and even his oldest attested son, Philip IV. The latter, commonly included with the other two sons (Antipater II and Alexander V) that Thessalonike bore, better fits as a son of an earlier marriage. The fate of Cynane II is unknown but she must have been at Pydna at the company of her sister Adea/Eurydice when Olympias carried out her purge.

Constructing the Legacy

Soon following this marriage, Cassander engaged in a series of public works intended to improve the economy as much as to promote his political image. Thus, Cassander founded the city of Thessalonica, on the shores of the Thermaic Gulf, naming it after the name of his wife. At about the same time, he rebuilt and reorganized Potidaea on the Pallene peninsula, changing its name to Cassandreia, so-called after himself. The most significant initiative was the reconstruction of Thebes twenty years after Alexander had destroyed it completely. With its reconstruction of Thebes, clearly motivated by the hate against Alexander’s memory, Cassander gained much appreciation across Boeotia and Attica.

Soon after getting hold of Macedon, Cassander launched a series of invasions against the Peloponnese where the weakened Polyperchon still resisted. Unable to remove the foe through force, Cassander managed to ensure the defection of Polyperchon’s son Alexander. His alliance with Alexander was however short as the latter was killed by the Sicyean Alexion in 314. Alexander’s widow Cratesipolis gathered the troops of her husband and entrusted them to Polyperchon’s command.

Campaign in Illyria

In the summer of 314, Cassander embarked on a campaign against Illyria where his natural enemy, Glaucias of the Taulantii, ruled. His first target was Apollonia, the prosperous colony in the southern Adriatic. He took the city at first assault and then drew his army against Glaucias. In a battle somewhere in central Albania, Cassander triumphed over Glaucias’ forces. In the post-battle terms, Glaucias committed to not waging war against Cassander and his allies; a commitment that he forgot as soon as Cassander left the area.

Next Cassander advanced with his army against the important city-port of Epidamnus (a.k.a. Dyrrachium). Unable to capture the city by brute force Cassander conquered it using the following stratagem: “When Cassander was returning from Illyris and was one day’s march from Epidamnus, he hid his army, and sending [a force of] cavalry and infantry he set alight villages situated high up towards the border between Illyris and Antintanis [Atintania], which were visible to the people of Epidamnus” (Polyaen. IV. XI. IV). When the Epidamnians came out of their defenses, supposing Cassander to have left the country, the hidden army came out and captured the city.

An Enemy of Antigonus

With Cassander emerging as triumphant over Polyperchon, Antigonus had no more reason to support Cassander. On the contrary, since the “One-Eyed” favored an unstable Macedon, he turned against Cassander and shifted his favor towards Polyperchon. Before the assassination of Polyperchon’s son Alexander, Antigonus had sent his general Aristodemus in the Peloponnese (in spring/summer 315). Alexander’s assassination and Cassander’s pressing demanded an increased presence of the Antigonids in Europe. Thus, with the help of the new Antigonid allies, Polyperchon continued to remain a thorn on Cassander’s side by holding an entrenched position in Corinth and Sycion.

Cassander could also implement Antigonus’ policy against him by promoting a disturbance across Antigonid possessions of Asia Minor. Thus, during the winter of 314-313, Cassander launched a military expedition into Caria, his first trans-Aegean venture. The force, supplied with troops from Macedon proper as well as from Munychia, was led into Caria by Cassander’s generals Asander and Prepelaus.

This expedition was in concert with Seleucus and Ptolemy’s movements against Antigonus in the same region. If successful in planting his own possessions in Asia Minor, Cassander could hope to keep the worst of the fighting away from his realms in Europe. However, the Macedonian had to check his ambitions after the failure of the expedition. Cassander troops were crushed after Antigonus’ general and nephew Polemaeus launched a night attack against either capturing or destroying them all.

The loss in Caria put a significant strain on Cassander’s military resources. From now onwards the tide of fortune would turn against Cassander, keeping him in Europe, playing defense against Antigonid actions.

Increased Antigonid Presence in Europe

To rebalance the conflict dynamics with Cassander, Antigonus sent his officer Telesphorus to the Peloponnese. He was to strengthen cooperation with Polyperchon and turn the Peloponnese into a buffer zone. This expedition was ultimately successful; by 313, Telesphorus had already succeeded in forcing Cassander out of the Peloponnese. The press increased during the summer of 313 when Antigonus sent Polemaeus in charge of 150 ships to Boeotia. Polemaues secured both the political and military support of the Boeotian League further limiting Cassandrean influence well within Hellas.

At the time of Polemaeus’ docking in Boeotia, Cassander was active in Euboea where he was not giving up on his expansive policies. To check Polemaeus’ actions, Cassander moved to Chalcis where he was met by another troubling news. With Macedon now left vulnerable, Antigonus sought to exploit the opportunity by moving into the Hellespont. Before this situation, Cassander could not afford to hold multiple fronts; he either was to stay in Euboea or return to Macedon. The Macedonian chose to return to Macedon in the winter of 313-312, keeping his domain secure there but leaving Polemaus free to take control of Greece. Pleistarchus, brother of Cassander who was left in command of a garrison in Euboea, could not present a challenge for Polemaeus.

Campaign in Epirus & Disaster in Illyria

With the southern Hellas completely lost, it was vital for Cassander to maintain the support of every garrison and every city that he could. Affairs were boiling in Epirus, a state key for Macedon’s western border security. Alcetas II had assumed the kingship of Epirus and had likely embarked into an anti-Macedonian/anti-Cassandrean policy. To reestablish influence in this state, Cassander sent there his general Lyciscus with an army.

In several battles against Alcetas and his two adult sons Alexander and Teucer, Lyciscus came barely victorious and still unable to dethrone Alcetas. Lyciscus’ losses were so severe that Cassander, alarmed at the news, came into Epirus with his own army. Rather than continuing a fight that could drag on and further deplete his resources Cassander settled a peace agreement with Alcetas. With Epirus now pacified, Cassander moved further north into Illyria, again set to subdue the city of Apollonia. The Apollonians had driven out the garrisons of Cassander and entered into the protection of Glaucias and his Illyrians. Dyrrachium had also been entrusted to Glaucias after liberating itself, with the aid of Corcyra and the Taulantii, from the Cassandrean garrison.

The campaign against Apollonia was a disaster for Cassander. The citizens, expecting a siege, were this time well prepared for it, as described by Diodorus: “Those in the city, however, were not frightened, but summoned aid from their other allies and drew up their army before the walls. In a battle, which was hard fought and long, the people of Apollonia, who were superior in number, forced their opponents to flee; and Cassander, who had lost many soldiers, since he did not have an adequate army with him and saw that the winter was at hand, returned into Macedonia” (Diod. XIX. LXXXIX. II.).

In addition to the military failure in Illyria, the policy of a stable, supportive Epirus failed as well. Soon after Cassander’s departure, the Leucadians removed the Cassandrean garrison from their citadel. Meanwhile, the internal affairs in Epirus remained problematic culminating in Three Hundred and Six with the murder of Alcetas. Rather as a punishment for his governance, the murder of Alcetas and his two minor sons was a move intended to deprive Cassander of allies in Epirus.

The Peace of the Dynasts

Cassander’s military actions in the course of 313 and 312 had little to no success. They resulted in an overall contraction of his political and military influence across the European part of the Macedonian empire. Polemaeus held a strong position in mainland Hellas with Antigonid forces sharing possession of the Peloponnesus with Polyperchon. In these circumstances, Cassander sought to establish a peace with Antigonus who also was prone to such an arrangement due to troubles he was having east. The peace talks held in the Hellespont included Ptolemy and Lysimachus as well and concluded the so-called Third War of the Successors.

The peace terms settled in 311/310, recognized the parties in their respective positions: Lysimachus in Thrace, Ptolemy in Egypt, Antigonus in Asia, and Cassander in Macedon. The peace was a political victory for Cassander; for the first time, he was recognized internationally as the sole regent ruler of Macedon in Europe. The only limited clause in his authority was that he was to enjoy his regency until Alexander IV reached maturity. Thus, it was no surprise that shortly after the agreement was reached, Cassander ordered the execution of Alexander IV (then about thirteen years old) and his mother Roxana. Glaucias (not to be confused with Glaucias of the Taulantii), who held them arrested at Amphipolis, carried out Cassander’s orders in 310. With the murder of Alexander IV Cassander had disposed of the last legitimate heir of the Argeads, eliminating more members of this family than any other. However, another claimant would threaten Cassander’s entire struggle for the rule in his own right.

The Claim of Heracles

After the execution of Alexander IV, Polyperchon, still entrenched in the Peloponnese decided to resume conflict with Cassander. With the aid of Antigonus, Polyperchon brought into Europe Heracles, Alexander the Great’s illegitimate son by Barsine. Using young Heracles as a claimant to the Macedonian throne, Polyperchon launched in 309 what was to be his final campaign against Cassander. The threat was real: Polyperchon gathered more than 20,000-foot soldiers and over 1,000 cavalrymen for his march north. With this force, he entered Epirus where he likely enrolled other Epirotes into his ranks. Polyperchon’s initiative could risk a hard-won peace between the Dynasts.

Polyperchon’s march towards Macedon had Cassander worried both on military and political grounds. Apart from the size of the army, Cassander was worried that his own troops would defect him and embrace Heracles as the true heir. Defections were common for that period. To prevent such a scenario Cassander entered into negotiations with Polyperchon to settle the conflict via diplomatic means. This time Cassander’s offers were generous for the old commander; Polyperchon was to be recognized as strategos of the Peloponesse and receive 4,000 Macedoanin foot troops and 500 Thessalian cavalrymen. Polyperchon’s private estate in Macedon, previously confiscated, was to return to its owner. All Polyperchon had to do in return is to kill Heracles.

The old commander duly accepted Cassander’s offer and had Heracles murder. With this elimination, the decade-long conflict between Cassander and Polyperchon was brought to an end. Cassander, without risking his chances on the battlefield, could not enroll Peloponesse in his sphere of influence through Polyperchon. From a previous persistent foe, Polyperchon served as Cassander’s ally in the Peloponnese; for the first time since he claimed Macedon, Cassander was without a direct challenge to his position.

Demetrius Poliorcetes’ Campaigns in the Name of Hellenism

During the remaining period of his reign, Cassander had to endure the assaults from his most dangerous enemy yet: Demetrius “the Besieger” (Poliorcetes), son of Antigonus. In June 307, Demetrius launched the most ambitious expedition in Europe taken by an Antigonid. With a fleet of 250 and 5,000 talents in money, Demetrius entered Piraeus. There, he duly expelled Cassander’s garrison at Munychia, even destroying that whole fortress. In the process, Demetrius captured Megara as well, there too expelling the Cassandrean garrison. Demetrius’ swift and brilliant campaign in southern Hellas, apart from the obvious losses, deprived Cassander of much manpower and revenue.

Demetrius’ incursion in mainland Hellas came with a promise for freedom for the whole country. The Antigonids were following a policy similar to that tried by Polyperchon fifteen years ago, though in a far more refined way. The promise for freedom at Cassander’s expense echoed in the whole region. Influenced by this momentum, the key region of Epirus installed the young Pyrrhus of Epirus on the throne with the aid of Glaucias of the Taulantii. Until 302, Epirus would remain in opposition to Cassander.

The Besieger would resume his expeditions against Cassander in 303 advancing dangerously into the Peloponnese. There, he got control of Acte and Arcadia (except Mantinea); expelled Cassandrean garrisons in Argos, Corinth, and Sicyon by bribes; and seized many cities without resistance. Demetrius even had time to preside over the games at Argos where he married Pyrrhus’ sister Deidameia. While in Hellas, Demetrius tried to rebuild the League of Corinth (founded by Philip II) into a new, rebranded organization. The renaming of Sicyon as Demetrias signaled the new reality that the Besieger could enforce on Cassander’s sphere.

The Allied Coalition

The victories of Demetrius across Hellas had worried not only Cassander but all the other Successors. If left unchecked, Antigonus and Demetrius could put all of Alexander the Great’s great empire under their yoke. To counter such a threat, Cassander joined a multinational effort to fight back against the Antigonids that included Lysimachus, Ptolemy, and Seleucus. In a nutshell, this effort would be similar to the concerted actions of the Allies against Germany during World War II. Notably, in a concerted fashion, Lysimachus with help from Cassander’s troops invaded northwestern Asia Minor; Ptolemy moved north from Egypt into Palestine; Seleucus marched westward from Babylon.

Pressed from all directions, Antigonus had to recall Demetrius from Europe in order to muster all that he could in one location. The opposing sides would meet in Ipsus for one of the greatest battles of the ancient era. The allied coalition, commanded by Lysimachus and Seleucus, fielded 64,000 infantry that included reinforcements from Cassander, 10,500 cavalries, 400 war elephants, and 100 Scythed chariots. Antigonus and Demetrius, joined also by Pyrrhus of Epirus, had brought up 70,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 75 elephants. The ensuing battle of Ipsus eventually concluded with a decisive victory from the allied coalition. The multitude of Seleucus’ elephants shattered the Antigonid forces. Antigonus himself was killed in battle while Demetrius and Pyrrhus fled, with few remaining forces, into Ephesus.

Conclusion

The victory at Ipsus came as a relief for Cassander who could aim to regain the lost possession beyond Macedon. Following the victory and partition of the territories of Antigonus, Cassander was awarded the possession of Caria and Cilicia in Asia Minor. The Macedonian left his brother Pleistarchus as a ruler subject to him in the new territories. Pleistarchus would ultimately lose Cilicia to Demetrius in 299/298. However, he managed to hold Caria, seemingly as late as 294.

Himself, Cassander could not enjoy the reign as he must have wished, with dropsy proving fatal to him in 297. Most of his reign he had lingered in constant wars and dynastic bloodsheds. Cassander’s vision of a lasting dynastic monarchy was ultimately wrecked in 294, with domestic bloodshed, as Cassander had once caused. Notably, Cassander’s son and his last surviving heir, Antipater II murdered his own mother Thessalonice only to be then killed by Lysimachus. The Antigonids were the ones to establish their own dynasty over Macedon.

Bibliography

Adams, W. L. (1993). Cassander and the Greek City-States (319-317 B.C.).

Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica. & Polyaenus, Strategems.

Hammond, N.G.L. (1989). The Illyrian Atintani, the Epirotic Atintanes and the Roman Protectorate. The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 79, pp. 11-25. Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies.

Kistler, J. M. (2006). War Elephants. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Lyngsnes Ø W. (2018). The Women Who Would Be Kings. Trondheim.

Pitt, E. (2016). The Contest for Macedon: A Study of the Conflict Between Cassander and Polyperchon (319-308 B.C.).

Sverkos, I. K. (2010). Macedonia in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods.