Apollonia: the Mighty Colony in Illyria

Apollonia was one of the most powerful Hellenic colonies in the Adriatic. It occupied a strategic position allowing for communication with the Illyrian, Greek, and Roman world. Thus, it led to notable economic prosperity but also put the city, on several occasions, in the midst of inter-state conflicts.

Early Development

Apollonia was founded in about 620 B.C.E., as a Corinthian colony. According to Herodotus, a contingent of soldiers from Apollonia took part in the battle of Salamis (480) against the Persians. Around 460 the Apollonians entered into a conflict with the Illyrian tribe of the Amantes, located in the interior. It seems that the colons aimed at expanding their domains south of river Aoos (modern Vjosa) and gaining the natural resources of bitumen in Nymphaeum (modern Selenica). The Apollonians emerged triumphant in this conflict and even invaded Thronion (modern Kanina), the then capital of the Amantes.

In 436, Apollonia sided with the democrats of Dyrrachium, the colony just north of it. These democrats were under blockade within the city from the opposing aristocrats. During the events that ensued, Apollonia turned as an important military base for the actions of the Corinthians, Leucadians, and Ambraciotes. These allies of Dyrrhachium’s democrats followed a land route via Apollonia to reach Dyrrachium in order to avoid the patrolling fleets of the aristocrat party and especially their ally, the Corcyraean fleet. The conflict would settle with the victory of the democrats and the defeat of the Corcyraean navy. This re-established stability in this region and transferred the conflict between the Hellenic states south, initiating the Peloponnesian War.

Prosperity

From 436 to 358 Apollonia would experience a period of peace and prosperity as a result of the good relations with the neighboring Illyrian kingdom of Bardylis. The rise of Philip II of Macedon that began by defeating Bardylis in the battle of the Lyncus plain forced the citizens of Apollonia to seek new allies, especially in Corinth. This is supported by the silver coins issued in the city that carried symbols copied from the Corinthian coins.

Apollonia was able to remain outside the borders of the expanded Macedonian state of Philip II and his son, Alexander the Great. The city maintained its autonomy until 314 when Macedonian forces of Cassander conquered it. The citizens were able to regain their freedom two years later with the help of the king of Illyria Glaucias, who controlled the northeastern hinterland, and the Corcyraeans. Apollonian forces repelled the following attempt of Cassander to regain the city.

In the period following the liberation from Macedonian rule, Apollonia maintained its autonomy. However, it collaborated productively with the Illyrian kings of the hinterland, Glaucias and then his successor, Monunious. The latter even established the capital of his state in the current village of Cakran, only 25 kilometers (15.5 mi) from the city of Apollonia. In about 275 the city may have temporarily fallen under the control of Pyrrhus of Epirus. The latter may have intended to use it as a base for communicating with southern Italy.

Roman Intervention

After the fall of Pyrrhus in 272, Apollonia regained its independence and re-established connection with the Illyrian state, this time controlled by Mytilus. The Apollonians succeeded in defending their liberty against incursions from Pyrrhus’ son and successor, Alexander.

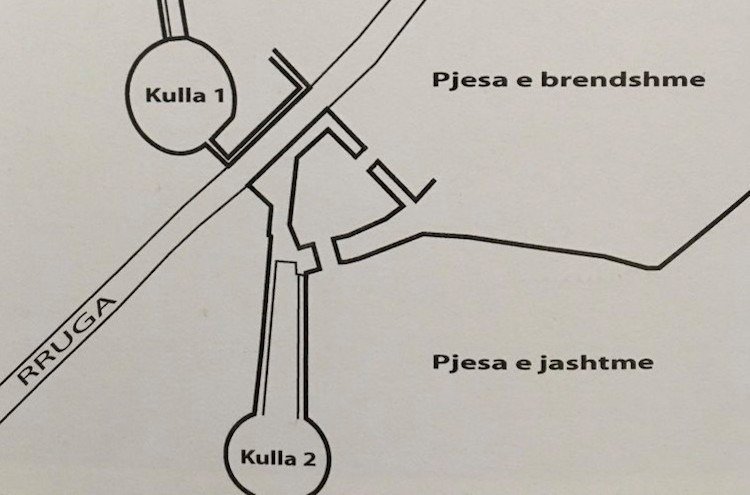

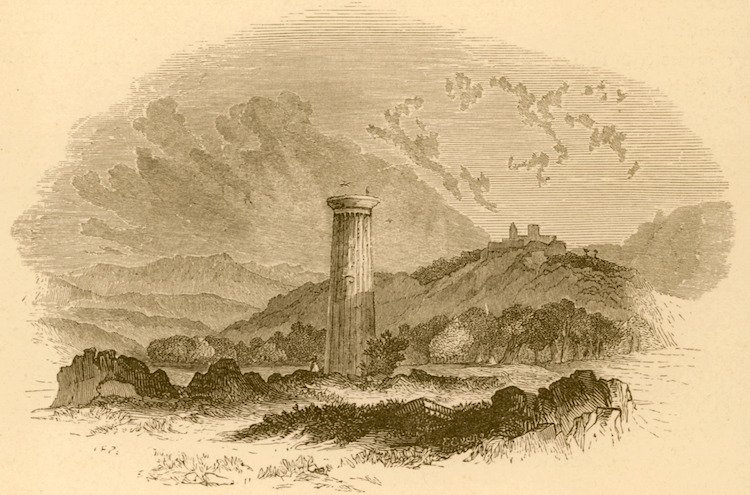

During this time, Apollonia established contacts with the Romans in attempts to find allies that would defend its autonomy. This makes Apollonia the first city east of Ionian Strait to establish official contacts with the Roman Republic. Meanwhile, the established peace allowed the city to develop and grow economically. The surrounding wall, theatre, nymphaeum, and other important public buildings were constructed. The city issued its own silver and bronze coins tailored for domestic use as well as for trading with the Illyrian hinterland.

The rising strength of the Illyrian kingdom of the Ardiaei threatened the independence of Apollonia. The Illyrians of queen Teuta, after having reduced the Epirote Republic, besieged the city in the spring of 229. The swift intervention of the Romans prevented the Illyrians from capturing Apollonia and other territories adjacent to it. This marked a turning point for the Apollonians. They had to detach themselves from their strong ties with the Greeks and learn to thrive in a Republic with imperial ambitions. In the period following the Roman intervention, Apollonia became part of the Roman protectorate created in the southwestern part of Illyria (current western lowlands of Albania).

Roman Rule

In the following years, Apollonia served more as a military base for Roman operations against Illyrians, Macedonians, and other states, rather than as a prosperous economic and civic center. In 214, the Apollonians along with the Romans, defeated the armies of the Macedonian king Philip V. The latter tried, without success, at least on two other occasions to capture Apollonia, in 211 and 205. In 199, the Roman consul Sulpicius launched from Apollonia his assault against the Macedonian kingdom. Sulpicius’ successor in command, Flaminius, defeated the Macedonians in the battle of the Aoos a year later. Thus, he removed the Macedonian influence from the whole region. In 148 the city of Apollonia became part of the Roman province of Macedonia and obligated to pay taxes.

During the I century renowned personalities visited Apollonia. In 84., Lucius Cornelius Sulla visited the city after travelling from Dyrrachium and also visited the nearby site of Nymphaeum. The famous Roman politician Cicero, impressed by its beauty, labelled the city “magna urbs et gravis” (“large and impressive city”). In 48 the city welcomed Caesar and supported him in his campaign against Pompey. In 44 the young Octavian Augustus studied in Apollonia accompanied by his friend Agrippa.

Octavian Augustus awarded Apollonia with the status of a free city exempted from taxes as a gratitude for its support for him and Caesar. Also, the citizens kept their institutions and enjoyed an expanded autonomy.

Decline

The city continued to serve as a key center of strategic importance until an earthquake of 234 C.E. This disaster caused severe destruction, ravaging most of it. It even changed the course of the river Aoos, shifting it away from the city. This made the old river port of the city obsolete and thus distanced it from the important seaborne trade. Thus, population abandoned Apollonia after this earthquake. No effort was made to rebuilt it as it was.

During the IV-V centuries Apollonia served only as a small episcopal center. In 431 the bishop Felix represented Apollonia and the nearby city of Bylis simultaneously in the Council of Ephesus. In later councils, there is no longer a mentioning of Apollonia. An inscription dated during Justinian’s reign (527 – 565) reveals a final attempt to repair the surrounding wall.

In the following centuries Apollonia was completely abandoned. Only a church was constructed near the ruins in the first quarter of the XIII-th century in Southern Italian and Byzantine style. The monastery took its current shape during the XIV-th century, becoming a gathering point for the small Orthodox population of the nearby villages of Myzeqeja. Contemporary authors mention one such village as Pollina since the XIII-th century. This Pollina corresponds to the current village of Pojan near the ancient remnants of Apollonia.