Battle of Paraitakene: The Mighty Clash In the Persian Wilderness

The Battle of Paraitakene was the second major battle fought between Eumenes of Cardia and Antigonus I “Monophthalmus” (“the One-Eyed”). It succeeded the battle of Orkynia (319 B.C.E.) and immediately preceded the decisive battle of Gabiene (316 B.C.E.).

Prologue

Eumenes of Cardia Before the Battle

The spring/summer of 318 brought a wave of good fortune to Eumenes. It was at this time when he and few of his followers “escaped” the year-long besiegement at Nora. By this time Polyperchon had succeeded the deceased Antipater into the regency position; it meant a change from a regent hostile to Eumenes into a supportive one. Eumenes’ escape was thus soon followed by an alliance between him and the new regent Polyperchon. According to this alliance, Eumenes had to keep Antigonus busy in Asia while Polyperchon dealt with Cassander. Argead women were also involved: Olympias, Alexander’s mother supported the pair Eumenes-Polyperchon while Adea/Eurydice the Antigonus-Cassander collaboration.

A formal order of Polyperchon allowed Eumenes to get under his service 3,000 Macedonian Silver Shields led by the experienced Teutamus and Antigenes. With them, the Cardian thought to fight Antigonus deep into the Persian wilderness where he could count on support from other governors. Thus, during the remainder of 318, Eumenes moved from Cilicia into Babylon; in his march, he recruited soldiers raising the number of his army into a total of 15,000 infantry and 3,300 cavalries.

Eumenes further doubled the size of his army in the spring of 317 with the forces of upper satraps. These reinforcements were respectively as follows: Eudamus (satrap of India) brought 500, 300 infantrymen, and 120 elephants; Stasander (satrap of Drangine) had with him troops from his province as well as those from Bactriane, 1,500 infantry, and 1,000 cavalries; Androbazus commanded 1,200 infantry and 400 cavalrymen from Paropanisadae; Sibyrtius (commander of Arachosia) came with 1,000 infantrymen and 600 cavalries; Tlepolemus (appointed satrap of Carmania) brought 1,500 infantry and 700 cavalrymen; finally there was Peucestas who had the largest force consisting of 10,000 archers, 3,000 infantrymen, and 1,000 cavalrymen. Having the largest force, Peucestas had also assumed the command of all the (aforementioned) forces coming from the upper satrapies; in total 18,000 infantry, 4,600 cavalrymen, and Eudamus’ war elephants.

Antigonus Before the Battle

Antigonus the One-Eyed tried to put a swift blow to Eumenes while he was still gathering forces in his march from Cilicia to Babylon. Thus, he pursued the Cardian with a lightly equipped force all the way into Babylon. By the time, however, winter came and both generals were forced to stay at their own winter quarters; Eumenes in or near Nippur (modern Nuffar, Iraq) while Antigonus somewhere in the outskirts of Babylon. By spring Antigonus learned of Eumenes’ doubling the size of his army by joining his army with those coming from easternmost provinces. As such, the One-Eyed had to abandon his plan of dealing with Eumenes quickly; instead, he began gathering his other troops and levying others for an expected clash of titanic proportions.

When Antigonus assembled a large army, he continued to pursue Eumenes’ in his path, confident in overcoming the enemy in a pitched battle. When his forces arrived in Susa, Eumenes had already left the city. Xenophilus, commander of Susa’s citadel and royal treasure there remained loyal to Eumenes keeping the gates shut. The One-Eyed left Seleucus with a force to maintain a siege of Susa while himself kept chasing Eumenes, now southwest, in the direction of modern Khuzestan.

In the present Khuzestan, Eumenes established a long frontier against Antigonus. Along the whole eastern bank of lower Pasitigris River (modern Karun River), Eumenes scouts were on guard. Though aware of the scouts’ presence, Antigonus intended to cross at the point where the Coprates River (modern Dez) joins the Pasitigris; somewhere near modern Chamm ol Hamid, north of Ahvaz, Iran. During the cross, the cavalry of Eumenes fell upon the vulnerable enemy, killing or forcing to drown about 5,000 and capturing 4,000. Antigonus with his main army on the other side had nothing to do but watch as Eumenes shattered his advance force.

Standoff before the Battle

Abandoning the cross westward, Antigonus moved north in Media to refresh the army and replace the losses.

After recovering from severe losses, the frustrated Antigonus moved first to meet Eumenes at Persia. Eumenes decided this was the right time to meet the One-Eyed on the field so he too, marched in his direction. The two mighty armies eventually meet each other at Paraitacene, separated between them by a river. After some time spent skirmishing, deserters appeared at the camp of Eumenes with the news of Antigonus intending to move the battle into Gabiene. As a place with large food supplies, Eumenes quickly decided he must occupy that place before Antigonus. Thus, the Cardian sent some of his own into Antigonus’ camp to pretend as deserters and say that Eumenes was about to attack. Meanwhile, the whole army of Eumenes’ broke camp with the heavy equipped soldiers and baggage marching first.

By dawn, Antigonus had realized Eumenes’ trick but did not give up the pursuit. Himself with the lightest cavalry he set for the enemy and had eyes on its forces soon after. Establishing himself in the hills above the army of Eumenes, Antigonus displayed his forces in a manner resembling that in the battle of Orkynia. Seeing the hostile forces above and thinking that the army of Antigonus had caught up with him, Eumenes hated the march and arrayed his forces for battle. Instead, Antigonus waited at his position until his rest (and heavier) army came up to that place too. By this maneuver, Antigonus nullified the initial plan of Eumenes and had finally had the Cardian involved in a pitched battle.

Battle Formations

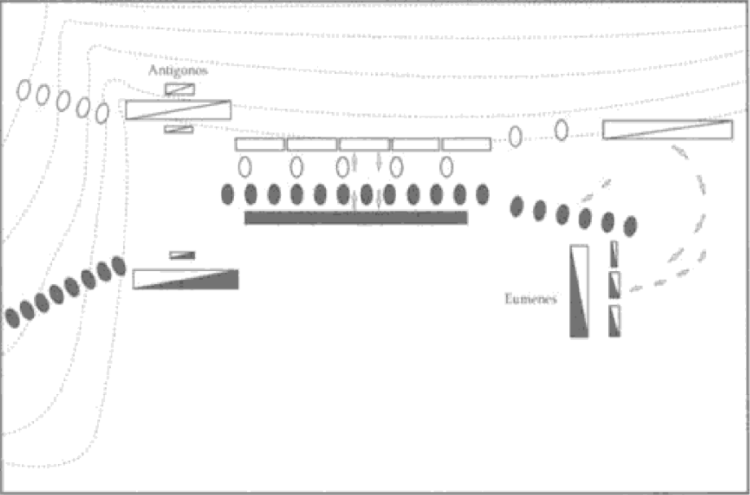

Eumenes’ Array

Eumenes deployed on his left-wing cavalry that mostly consisted of 3,400 eastern allies. This force was led by Eudamos, satrap of India who had brought the Elephants from there. In front of this cavalry stood a hundred lancers ordered to blunt any assault. The heavy infantry occupied Eumenes’ center. As the infantry line approached the right-wing, it consisted of stronger troops; first 6,000 mercenaries, then 5,000 troops from mixed backgrounds arrayed as pikemen, and finally, the 3,000 Silver Shields (Argyraspids). Immediately to their right, Eumenes placed his own unit of 3,000 Hypaspists, who, as the Silver Shields, had served under Alexander.

Eumenes himself took charge of the far right-wing with 2,900 horsemen. This was Eumenes’ strongest wing, consisting of 900 Companions as well as hand-picked troopers shielded, in addition, by two small forces.

Across the whole front line, Eumenes spread equally all the elephants, thus screening the infantry as well as protecting the beasts’ flanks. The gaps between the beasts were filled with light infantry units such as archers, javelin men, and slingers, in imitation of King Porus’ array at the Hydaspes.

In all, Eumenes deployed 35,000 infantrymen, 6,100 mounted men, and 114 elephants.

Antigonus’ Array

Antigonus’ dare in his march had allowed him the possession of the higher ground of the battlefield. Thus, the One-Eyed arrayed his forces in response to the array Eumenes had already committed to. This same position allowed Antigonus to be the one taking initiative first.

Having noticed Eumenes’ strong right-wing, Antigonus prepared his own left accordingly. Here, he deployed 5,000 of his fastest and lightest cavalrymen under the command of Peithon, satrap of Media. Antigonus instructed this wing to avoid direct confrontation with the much stronger wing on the opposite. He thus intended to delay confrontation in his weakest side during which he would seek victory on the other flank. Thus, he concentrated the strongest force on the right-wing where he himself stood in command. Here, he had with him on the far right an elite unit of bodyguards (agema).

In between Antigonus and the infantry line close to him stood his young son Demetrius (“the Besieger”) with 1,000 Companions. Close to this right-wing stood also the strongest part of the infantry, 8,000 Macedonian pikemen. Then, as the line moved onto his left, the deployed units were less strong: 8,000 recruited natives trained in phalanx formation; then came 3,000 Anatolian mercenaries and, near Peithon’s squadron of cavalry, 9,000 other phalangites, also serving as mercenaries.

Unlike Eumenes, Antigonus had a lesser number of elephants. Thus, rather than spreading them equally across his front, he kept the best 30 beasts with him on the right. The remaining elephants stood on the center, and only a handful on his left-wing. As Eumenes, Antigonus intended to use the elephants to screen and shield his forces.

In all, Antigonus fielded 28,000 infantry, about 8,500 cavalry and 65 elephants.

Battle

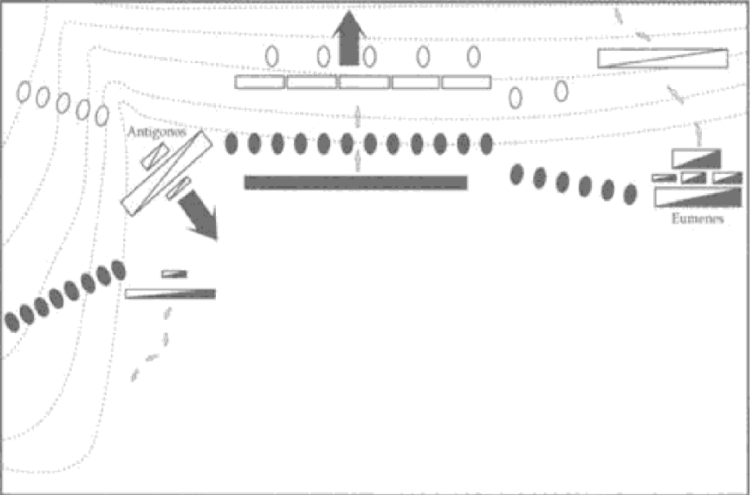

Broken Oblique

As expected, Antigonus launched the offensive by dissenting down his high ground in oblique formation led by his right. The sight would have been dramatic for Eumenes’ forces below but all of them stood their ground. As Antigonus moved down, he sought to find a weak point to breach in Eumenes’ left, unable to find one on the spot. In fact, Eumenes’ left had made use of a higher ground that protected it firmly from outflanks, along with numerous elephants. On the other side, the plain was level, luring Peithon into outflanking maneuvers but compromising Antigonus’ whole strategy of a fight in oblique formation.

“Peithon’s cavalry…by riding around the wing and making an attack on the flanks…kept inflicting wounds [on the hostile elephants] with repeated flight of arrows, suffering no harm themselves because of their mobility but causing great damage to the beasts, which because of their weight could neither pursue nor retire when the occasion demanded. When Eumenes, however, observed that the wing was hard pressed by the multitude of mounted archers, he summoned the most lightly equipped of his cavalry from Eudamus who had the left wing. Leading the whole squadron in a flanking movement, he made an attack upon his opponents with light armed soldiers and the most lightly equipped of the cavalry. Since the elephants also followed, he easily routed the forces of Peithon and pursued them to the foothills”. (Diod. XIX. XXX.).

Antigonus’ Offensive

Eumenes’ infantry, led by the strength of the Silver Shields came up victorious against the enemy phalanx. They even pursued the enemy as they fled as far as the foothills. However, with both Eumenes’ right and center pursuing the enemy far ahead, the array was no longer compact; the left-wing and that infantry siding them were left vulnerable behind. Furthermore, Eumenes had countered Peithon’s offensive by moving forces from his left to the right-wing.

Realizing an opportunity in his own right, Antigonus advanced deeper with his cavalry, exploiting a gap in Eumenes’ left-wing. The troops who suffered from this charge were those stationed with Eudamus, Eumenes’ “master of elephants”. “Because the attack was unexpected, he [Antigonus] quickly put to flight those who faced him, destroying many of them; then he sent out the swiftest of his mounted men and be means of them he assembled those of his soldiers who were fleeing and once more formed them into a line along the foothills. As soon as Eumenes learned of the defeat of his own soldiers he recalled the pursuers by a trumpet signal, for he was eager to aid Eudamus”. (Diod. XIX. XXX).

The combat continued on the station of Eudamus until nightfall. Rather than a fight to the last, the final combat was of a skirmishing nature. Both sides were seeking to regroup and retreat safely. With the fall of the darkness, the forces disengaged each other thus concluding the whole battle.

Aftermath

It was evident for all the involved that the battle fought was inconclusive. Both Eumenes and Antigonus knew that it would take at least another battle for them to settle their quarrel. However, the battle of Paraitakene was a tactical victory for Eumenes. This is supported by Diodorus who confirms that there were more victims on Antigonus’ side. Specifically, at least 3,700-foot soldiers and 54 horsemen fell from the army of Antigonus (plus more than 4,000 wounded); those killed fighting for Eumenes consisted only of 540 infantrymen and a handful of horsemen (with more than 900 wounded).

Noticing the low morale of his forces, Antigonus decided to move away at full speed from the sight of Eumenes’ army. With this move, the One-Eyed prevented potential mass desertion from his army to that of Eumenes. Now at a distance, Eumenes thought that Paraitakane had concluded the campaigning season. The Cardian withdrew into winter quarters in good spirit not expecting a battle for another season. His expectations would prove wrong, with the decisive battle taking place much sooner.

Bibliography

Anson, E. M. (1977). The Siege of Nora: A Source Conflict.

Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica.

Pietrykowski, J. (2009). Great Battles of the Hellenistic World. Pen & Sword Military.

Plutarch. Life of Eumenes.