Battle of Asculum: The Truth About Pyrrhic Victory

The battle of Asculum was fought in 279 B.C.E., between Pyrrhus of Epirus and the Roman Republic. The battle took place near Asculum (modern Ascoli Piceno) at a marshy terrain near river Carapelle.

Prologue

Pyrrhus before the Battle of Asculum

After the victory at the battle of Heraclea (280 B.C.E.), Pyrrhus and his army wintered in Tarentum. During this time he and the Romans discussed a potential peace agreement. Initially, Pyrrhus achieved a peaceful resolution in principle with the Roman commissioner Gaius Fabricius Luscinus Monocularis. Yet, under Carthaginian influence, the Roman Senate overturned the agreement; a decision attributed to an anti-Pyrrhic speech by the influential Roman politician Appius Claudius.

As such, Pyrrhus prepared for another battle with the Romans. With the coming of spring 279, Pyrrhus broke camp and set for Apulia. The Epirote king had assembled about 70,000 footmen (of which 16,000 were the forces he had brought with him across the sea). He could also count on more than 8,000 horsemen and 19 elephants. In Apulia, the king of Epirus tried to dismantle a chain of Roman colonies that surrounded the Samnites; mainly Venusia (modern Venosa) established as a colony by the Republic in 291, and Luceria (modern Lucera).

Rome before the Battle of Asculum

After the loss at Heraclea, the Roman Republic was on the verge of signing a somewhat unfavorable treaty with Pyrrhus. According to this settlement, the Romans would let go of their claims on Magna Graecia and accept Pyrrhus as a negotiator for resolving conflicts related with this region. The Carthaginians had followed the affairs in the region closely, afraid that if Pyrrhus settled with Romans, he would be free to deal with Carthaginian strongholds across Sicily. Thus, in the immediate period preceding the battle of Asculum, the Carthaginian commander Mago (grandfather of Hannibal) docked with 120 ships at Ostia near Rome. He offered the Carthaginian assistance in the war against Pyrrhus as long as Rome continued the fight against the Epirote king. Eventually, the Senate accepted the alliance and turned down a peace with Pyrrhus.

By spring of 279, the Romans had assembled an army of more than 70,000 men. About 20,000 of them were from Rome itself while others were recruited among the central Italic allies. Of cavalry, the Romans put together 8,000 horsemen in total. This force was placed under the command of the two yearly consuls, Publius Decimus Mus and Publius Sulpicius Saverrio. They moved ahead to meet Pyrrhus in Apulia and prevent the enemy from capturing their Apulian colonies.

Romans’ Array

Four legions made up the Roman infantry. At the far left stood the Legio I supplied, in addition to the Romans, by the Campanians and the Sabines. Legio II stood at the far right including in its ranks the Frentanians. Legio III and Legio IV were the central formations. The allies included in the first were the Umbrians and the Volcians; those included in the later were the Marucini and the Peligni. Italian light infantry filled up the gaps between the legions. Roman and allied cavalries occupied both flanks.

The Romans felt more prepared to face the enemy elephants this time, having already faced them at the battle of Heraclea. For this, they had placed on each wing a contingent of about 150 anti-elephants ox-wagons (300 in total). These wagons had caltrops against elephants’ feet, swinging blades to cut their trunks, and fiery-grappling hooks to hit and burn them.

Pyrrhus’ Array

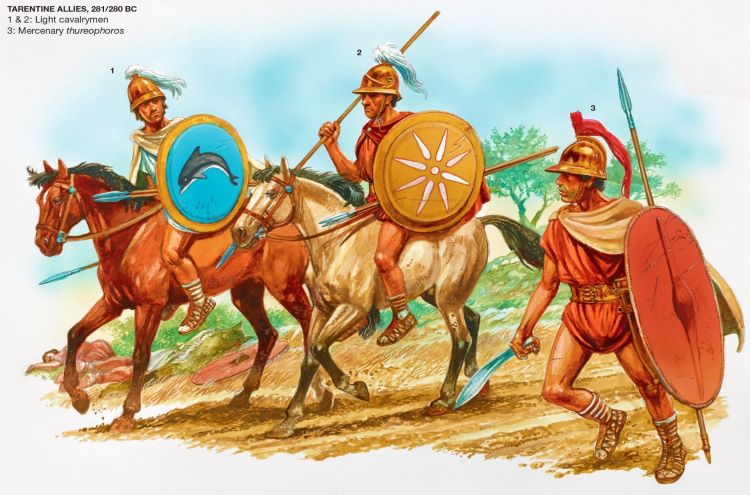

At his far right, Pyrrhus placed the phalanx of the Macedonians and the Ambracians. On the left, Pyrrhus arrayed the Samnite phalanx aided on the flank by the Aetolians, Acarnanians, and Athamanes. In the center were positioned the infantry of southern Italian allies (Tarentines, Bruttians, and Lucanians) and that of the native from Epirus (Molossians, Thesprotians, and Chaonians); facing respectively the Legio III and Legio IV. It’s tempting to compare Pyrrhus’ center with that of Hannibal at Cannae; yet the former’s central deployment appears more disciplined than the latter’s intentional wavered center.

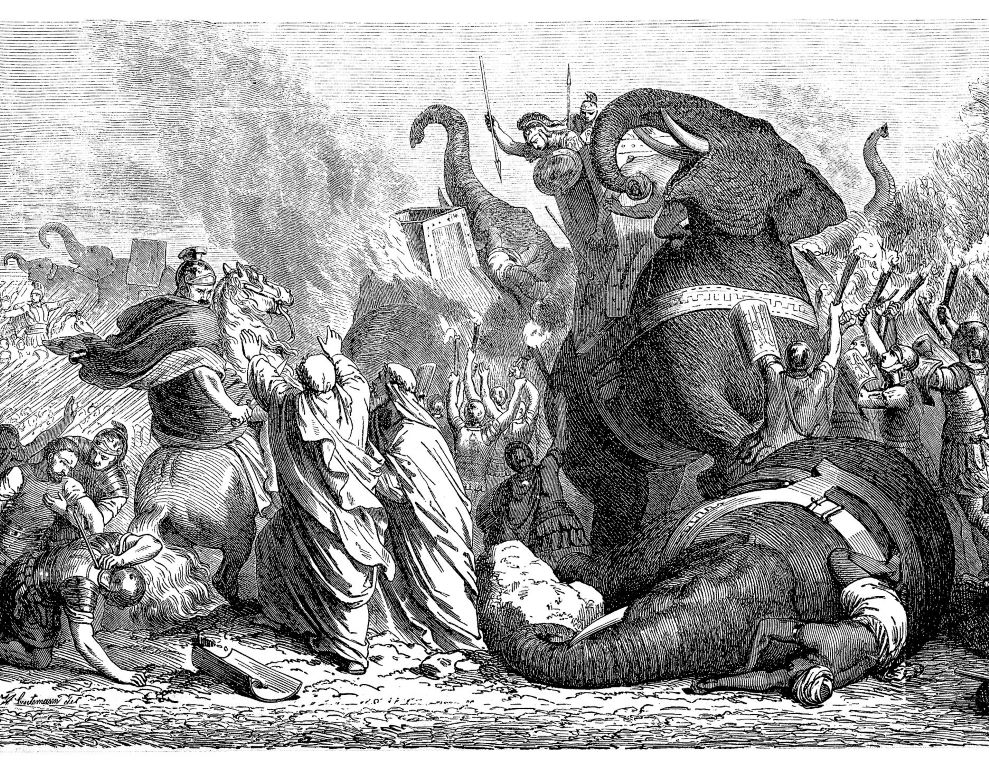

On his right wing, Pyrrhus drew the Thessalian and Samnite cavalries; on the left wing rode the Lucanian, Ambracian, and allied-Hellenic cavalries. Himself, with the royal guard (agema), Pyrrhus rode along the back lines, prepared to aid where the circumstances would require. The position of his 19 elephants is less clear meaning they were more mobile than in the previous battle. Because Pyrrhus noticed in advance the anti-elephant waggons of the enemy, arrayed on both wings, he changed his initial deployment; rather than keeping elephants on his wings he threw them right against the Roman infantry. This action promised dual benefits: it would keep the elephants away from the hostile waggons and could shatter the infantry lines of the Romans.

Pyrrhus elephants were effective in long range as well. The king of Epirus was among the first in the west to mount towers with archers on elephants’ backs. As such, rather than merely deploying them as a variation of a heavy cavalry, Pyrrhus had turned the beasts into mobile artillery units.

The Opening Stage

Unlike in the battle of Heraclea, Pyrrhus did not invest in protecting his side of the river. Since unlike Heraclea, the terrain along the river banks were marshy, swampy, and wooded, Pyrrhus sought to avoid that battlefield. In the marshes he would diminish the stability of his phalanx and put his heavy elephants in a challenging situation.

As such, the Romans crossed the river unharmed and met the forces of Pyrrhus on his side of the river. The first to clash were the cavalries on the wings. Roman horsemen were inferior in riding skills to those of Pyrrhus’ riders. At the time, when in close quarters, the Romans would step off their horse and seek hand-to-hand combat. This tactic was no match for the dynamic cavalry of Pyrrhus. His right wing cavalry, led by the Thessalians, outmatched the enemy with hit and run tactics into diamond formation. The left wing, the Tarentine cavalry, a Pyrrhic invention, defeated their opponents by striking them at a distance and avoiding close encounters.

Then, Pyrrhus dealt with the anti-elephant waggons. He ordered his slingers and archers to target the foes operating these waggons. Showered with arrows and harassed by the cavalries, the Romans abandoned the waggons and fled the battlefield.

Truth or Dare?

A “Pyrrhic Victory” Is a Victory

Ancient authors have provided conflicting accounts on the battle of Asculum. They seem to follow a Roman narrative of trying to present the Romans in a favorable position. Some go as far as treating the battle as a tie or indecisive clash. However, almost all agree that this was the battle after which the term “Pyrrhic victory” was coined, meaning a victory at a great loss. Since this brought the famous phrase “Pyrrhic victory”, one must then accept that the battle of Asculum was, indeed, a victory for Pyrrhus, not a tie. In fact, even the pejorative term “Pyrrhic victory” seems a Roman propaganda trying to diminish the success of a rather solid victory.

Dionysius also reported that Pyrrhus was wounded by a javelin in the arm at Asculum. Plutarch cites this but does not report it as his own assessment.

Due to the Roman propaganda affecting the narrative, there are some noises in the sources that we must clear out. First, according to Plutarch, the battle of Asculum took place in two days, with the second day bringing victory for Pyrrhus. In Dionysius’ account, which Livy then follows, the second day lacks or is intentionally omitted. Dionysius also reports that Pyrrhus was wounded by a javelin in the arm at Asculum. The highlight on Roman heroisms and omission or manipulation of acts reflecting Pyrrhus’ dominance served the Roman interest in emulating a glorious memory. Plutarch’s account, on the other hand, is more reliable.

Suspicious Episodes

We also must treat with caution some patriotic episodes described by Dionysius. Accordingly, the anti-elephants wagons came into contact with the elephants. This is highly unlikely since the same author admits that Pyrrhus’ cavalry defeated their enemies on both wings. It’s on the wings where the anti-elephant waggons were stationed. Thus, they would have been the next immediate target of the winning cavalry. Furthermore, since Pyrrhus had noticed the anti-elephant waggons of the enemy, he purposely kept his elephants away from the wings.

Another episode of Dionysius mentions the Daunians from the city of Arpi as assaulting and pillaging the Epirote camp. In response, Pyrrhus sent the elephants and cavalry against them, but since the Daunians fled, then he turned the mounted units around and rammed them against the center of the enemy. It’s unlikely that Pyrrhus would send the slow elephants to respond to an urgency such as a camp assault from hostiles. Instead, the movement of elephants from the wings, back, and to the center, makes sense only in terms of the battle at hand. The pillage of the Epirote camp from some Daunians is likely an invention.

The Battle

Fight on the Center

The battle of the infantry went Pyrrhus’ way as well, although at the center the Romans were more competitive. The Romans legions had already lost their protection from the flanks so they were already in danger of being surrounded. However, by advancing within the enemy’s central ranks they avoided attacks of Pyrrhic cavalries from the wings.

The Macedonian phalanx of Pyrrhus repulsed the Legio I of the Romans with ease. The Samnite phalanx, aided by the Aetolians, Acarnanes, and Athamanes, held their ground against the Legio II. The Legio III and IV pushed forward and routed the Lucanians and Bruttians as well as the Molossians, Thesprotians, and Chaonians. When these legiones advanced too far, Pyrrhus sent his right wing cavalry, elephants, and rammed them against the persisting foes. Surrounded on all sides, the two Roman legions escaped the fight and sought refuge on the forested high grounds.

“The elephants, accordingly, being unable to ascend the height, caused them no harm, nor did the squadrons of horse; but the bowmen and slingers, hurling their missiles from all sides, wounded and destroyed many of them. When the commanders became aware of what was going on there, Pyrrhus sent, from his line of infantry, the Athamanians and Acarnanians and some of the Samnites, while the Roman consul sent some squadrons of horses, since the foot needed such assistance. And at this same time a fresh battle took place there between the foot and horse and there was still greater slaughter”. (Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, Excerpts from Book XX. IIII, VI).

After this, the sun set and the armies regrouped at their camps, at opposite sides of the river.

Pyrrhus’ Decisive Assault

According to Plutarch, the fighting resumed the next day. Pyrrhus, more accustomed to the terrain, had occupied the most favorable parts of it. “He put grreat numbers of slingers and archers in the spaces between the elephants and led his forces to the attack in dense array and with a mighty impetus. So the Romans, having no opportunity for sidelong shifts and counter-movements, as on the previous day, were obliged to engage on level ground and front to front: and being anxious to repulse the enemy’s men-at-arms before their elephants came up, they fought fiercely with their swords against the Macedonian spears, reckless of their lives and thinking only of wounding and slaying, while caring naught for what they suffered. After a long time, however, as we are told, they began to be driven back at the point where Pyrrhus himself was pressing hard upon his opponentsL but the greatest havoc was wrought by the furious strength of the elephants, since the valour of the Romans was of no avail in fightings them, but they felt that they must yield before them as before an onrushing billow or a crashing earthquake…”. (Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus, XXI, V, VI-VII).

Epilogue

Aftermath of the Battle

The aforementioned assault is Pyrrhus best example of using unit-by-unit fighting formation (parentaxis) as described by Asclepiodotus (VI.I) and not individual fighting (kat’andra). Also, the use of light infantry, javelineers, and archers between the elephants proved effective against the Roman pila.

Modern scholars agree that the battle of Asculum was a solid victory for Pyrrhus of Epirus. Among them, Pierre Cabanes wrote that in Asculum Pyrrhus “achieved a splendid victory” (Historia e Adriatikut). On the number of the casualties, Hieronymus of Cardia, as cited by Plutarch, is the most trusted source. Accordingly, the Romans lost 6,000 whereas Pyrrhus lost 3,505 men. Based on these numbers, the number of the fallen from the side of Pyrrhus are quite moderate. Yet, the Epirote king was reported in classical sources managing a difficult post-match situation.

The famous episode that brought the phrase “Pyrrhic victory” went as follows: a friend of Pyrrhus came to him, after the battle, and congratulated him on the victory. To him Pyrrhus replied, “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined”. (Plutarch, Pyrrhus) If the numbers reported by Hieronymus are true as they seem to be, it’s hard to imagine Pyrrhus ever phrasing this reported remark. The sentence, though, makes more sense only if Pyrrhus had an unstable emotional moment after the battle. Two thousand years later, Napoleon III was caught up in a similar unnerving state after the battle of Solferino (1859).

After Asculum, Pyrrhus decided to pause his wars against the Romans and accept the invitation of Syracuse against Carthage. The next year he crossed into Sicily where he fought for two years. Pyrrhus’ absence in the peninsula allowed the Republic to replenish its resources and begin regaining its southern possessions.

Bibliography

Armstrong, J. (2017). The Campaigns of Pyrrhus, 282-272 B.C. Part IV. The Macedonian Age and the Rise of Rome.

Cabanes, P. (2001). Historia e Adriatikut (Histoire de l’Adriatique. Editions du Seuil, 2001. Shtëpia e Librit & Komunikimit.

Dionysi Halicarnassensis. Antiquitatum Romanarum. Excerpta / Fragmenta. XX.

Eramo, I. (2015). Pyrrhus. The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army.

Montanelli, I. (1997). Historia e Romës (Storia di Roma). RCS Libri S.p.A. Milano. BESA.

Plutarch. Life of Pyrrhus.