The Battle of Beneventum: The Untamed vs the Uncorrupted

The battle of Beneventum was the third and last battle fought between Pyrrhus of Epirus and the Roman Republic. It took place in Beneventum (modern Benevento) of Campania in 275 B.C.E. Prior to the battle, the place was known as Maleventum (meaning “bad event” as to suggest a place of bad omens). The Roman forces were led into the battle by Manius Curius Dentatus, one of the yearly consuls.

Pyrrhus and Rome before the battle of Beneventum

Pyrrhus before the battle

After the battle of Asculum, Pyrrhus had spent the 279-276 period away from Italy, campaigning against the Carthaginians in Sicily. He even came within the ace of expelling the Carthaginian forces from the whole island; Carthage managed to keep her presence in the island only by holding at all cost a foothold in Lilybaeum (modern Marsala). By 276, the king of Epirus, tired of the intrigues of the Sicilians, decided to cross from Sicily into the heel of Italy.

The crossing back into Italy was not easy. Carthaginian ships assaulted the Sicilian ships carrying the forces of Pyrrhus across the strait; an assault that caused the loss of some of the army and the ships. The remaining fleet disembarked with difficulty near Rhegium (modern Reggio Calabria). There again, Campanian bandits assaulted Pyrrhic forces causing some casualties in the rear until Pyrrhus himself intervened. The Epirote adventurer even received a non-fatal wound in the head but he eventually repelled the Campanian assault. The remaining journey from Rhegium into Tarentum was done in safety.

Upon his return into mainland Italy, Pyrrhus had under his command a core force of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalries. He added to those other reinforcements from Tarentum consisting of his stationed troops there and Tarentine allies. This raised the total number of Pyrrhus’ army to more than 30,000 troops.

Rome before the battle

During the four-year absence of Pyrrhus from Italy, the Romans had tried to regain the influence lost. The degree to which the Romans succeeded in this remains unclear; they did get the Samnites under their control but that was all they achieved. As such, the Romans did not sweep the heel of Italy in Pyrrhus’ absence as some have suggested. What they had done, however, was to better prepare against the forces of the Epirote king. Notably, the Romans had found the right strategy on dealing with the hostile elephants, a strategy they were about to execute at Beneventum.

Having learned about the Pyrrhus’ preparations, the Romans gathered two forces each led by the yearly consuls, Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Caudinus and Manius Curius Dentanus respectively. The former took the field in Lucania while the latter marched into Campania. Dentanus, with 25,000 men, set his camp there, near the town of Beneventum.

The Battle of Beneventum

Pyrrhus’ Forced March

Despite the sources at hand, the so-called battle of Beneventum remains obscure; classical sources agree it was a Roman victory. Modern reassessments suggest that the result of this battle was indecisive, the Roman victory being an invention. However it may be, we have no option but to rely on the classical sources to reconstruct the combat.

On learning that the Romans were divided into two separate forces, the Epirote thought to deal with them separately. For this, he sent a small force in Lucania (central Basilicata), to keep Caudinus’ busy and away from joining the other army. Having stalled Caudinus in this way, Pyrrhus himself with all his force set out against the army of Dentatus at Beneventum. The king of Epirus had with him about thirty thousand men.

In contrast with his two previous battles against the Romans, this time Pyrrhus took the initiative. Having stalled one of the consular armies in Lucania, the Epirote moved north with all his forces, at full speed against the army at Beneventum, Campania.

In order to catch this Roman army by surprise, Pyrrhus tried a forced march during the night against the enemy to reach them unaware by dawn. The march proved more difficult than expected in difficult and foreign terrain. Thus, it took a bit longer for the forces to reach the camp of the Roman army. When they came within sight of the hostile army, the Romans were already up and could notice the antagonists in daylight. The Romans were indeed surprised by the sight of the enemy but could, however, organize their lines in time. As it stood, Pyrrhus faced an army fresher than his more tired force; yet, he chose to stay there and fight.

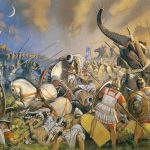

Beasts Run Wild

When the forces clashed, the Romans pushed against the tired Pyrrhic lines. According to Plutarch, “Manius…led his forces out and attacked the foremost of the enemy, and after routing these, put their whole army to flight, so that many of them fell and some of their elephants were left behind and captured. This victory brought Manius down into the plain to give battle; here, after an engagement in the open, he routed the enemy at some points, but at one was overwhelmed by the elephants and driven back upon his camp, where he was obliged to call upon the guards, who were standing on the parapets in great numbers, all in arms, and full of fresh vigour. Down they came from their strong places, and hurling their javelins at the elephants compelled them to wheel about and run back through the ranks of their own men, thus causing disorder and confusion there. This gave the victory to the Romans”. (Plut. Pyrrhus. XXV. VI-VIII).

The release of the elephants failed to deliver the same results to the king of Epirus as in the previous engagements. Not only were the Romans now more accustomed to the beasts but they adopted, this time, an effective tactic against them. At Beneventum, the Romans reaped the benefits of the so-called “flaming pig” strategy. By literally setting pigs on fire and throwing them at the elephants the Romans were able to force them to flight. The elephants even went wild, as in Plutarch’s account, and turned against their own lines. Outmaneuvered in flanks and pushed on the front, Pyrrhus signaled the retreat.

Aftermath

After the battle of Beneventum, Pyrrhus decided to give up his campaigns in the west and return to his homeland. Pausanias tells of a final tentative from Pyrrhus to throw the Romans into confusion. According to Pausanias’ “Attica” (XIII. I), Pyrrhus asked for money and troops to Antigonus Gonatas, king of Macedon, and Antiochus I. When they refused, Pyrrhus acted as if Antigonus and other allies were coming to his support. The Romans, unfazed by the potential of a larger foreign involvement, held the same hostile position against Pyrrhus. The king of Epirus eventually left Italy and returned to Epirus with 8,000 infantry and 500 horsemen. Back in the peninsula, the Roman renamed the site of the battle from “Maleventum” into “Beneventum”, thus commemorating their triumph over Pyrrhus.

After Pyrrhus left Italy it was only a matter of time for the Roman Republic to gain control of the whole peninsula. In 272, only three years after the Epirote king’s departure, Tarentum fell under Roman control. After Tarentum, all other Hellenic colonies across southern Italy fell one after the other: Heraclea (modern Policoro), Croton (Crotone), Locris (Locri), Metapontion (Metaponto), and Thurii (Sibari). The so-called Italic populations suffered the same fate; in 268 Beneventum accepted a Roman colony; the Lucanians, Bruttians, and Iapygians/Apulians settled for the Roman conditions. Soon, the Roman Republic had control over the entire coast from the mouth of the Po into the Otranto Strait. Here, they conquered the strategic port of Brundisium (Brindisi) between 268 -264; a conquest that would prove key in further expansion east.

Bibliography

Armstrong, J. (2017). The Campaigns of Pyrrhus, 282-272 B.C. Part IV. The Macedonian Age and the Rise of Rome.

Cabanes, P. (2001). Historia e Adriatikut (Histoire de l’Adriatique. Editions du Seuil, 2001. Shtëpia e Librit & Komunikimit.

Dionysi Halicarnassensis. Antiquitatum Romanarum. Excerpta / Fragmenta. XX.

Eramo, I. (2015). Pyrrhus. The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army.

Montanelli, I. (1997). Historia e Romës (Storia di Roma). RCS Libri S.p.A. Milano. BESA.

Plutarch. Life of Pyrrhus.

Under Pyrrhus, the Epirote Army soon transformed into a significant military force thanks to the major use of contingents provided by allies or mercenaries. When the ambitious king landed in Italy, his expeditionary army comprised the following: 17,500 infantrymen, 2,000 archers, 500 slingers, 2,400 cavalrymen and twenty war elephants. It is interesting to note that Pyrrhus was strongly supported by Ptolemy Keraunos during the organization of his Italian expedition: the usurper of Seleucos’ dominions and army sent him the twenty war elephants, 400 cavalry and 5,000 infantry, all veteran soldiers. Of these, 2,500 were Macedonian phalangists and 2,500 excellent asiatic light troops. The heavy infantry of the Epirote Army was completed by 3,000 phalangists from the city of Ambracia (the only significant urban centre of Epirus, conquered by Pyrrhus, who made it the new capital of his kingdom) and 9,000 `real’ Epirotes (Molossians, Chaonians and Thesprotians) also equipped as phalangists. The 9,000 Epirotes were also organized into three different units of 3,000 men, corresponding to the three main tribal groups of Epirus. The remaining 3,000 infantry were all lightly equipped Greek mercenaries: Aitolians, Athamanians and Acarnanians. The 2,400 cavalry comprised 1,700 heavy cavalrymen from Epirus and 700 light cavalrymen. The 1,700 heavy cavalry was formed by the aristocracy of the kingdom, as in Macedonia, apparently comprising an elite royal squadron of 500 men (acting as the mounted bodyguard of the king) and four `line’ squadrons with 300 soldiers each. The 700 light cavalry included 300 Thessalians and 100 Macedonians sent by Ptolemy Keraunos and 300 Greek mercenaries (Aitolians, Athamanians and Acarnanians). After its arrival in Italy, the army was supplemented by the military forces of Taras and large numbers of allied/mercenary Italic warriors from several different peoples.