Polyperchon: Unlucky or Unskilled General?

Polyperchon was a general who served in the ranks of Alexander III the Great and later fought for imperial rule. He was born sometime in the time frame 394 – 380 B.C.E., as the son of Simmias from Tymphaia, a rough and remote area under the Pindus. Tymphaia was incorporated into the Macedonian state in 350. Yet, the Tymphaei/Tymphaios remained closer culturally to neighboring Epirus. This connection can explain the later political alliance between Polyperchon and Olympias of Epirus, mother of Alexander.

Polyperchon’s “Early” Career

Polyperchon followed Alexander in his epic campaign in Asia as the commander of the Tymphaian infantry squadron. He was promoted into the rank of general prior to the battle of Gaugamela in 331. Polyperchon’s first recorded sole command came in the spring of 326 in Gandara (Persian: Gandâra) near modern Kabul. During this advance, he captured the town of Ora in the Soastus (Swat) valley.

Sources describe Polyperchon as a conservative man, resisting the open policy towards the orientalism of Alexander. He shared these same views with other generals whom he befriended such as Antipater, Parmenion, and especially Craterus. Polyperchon even mocked the adoption of the Persian court ritual (proskynesis) by Alexander.

The generals’ conservative mindset influenced Alexander’s decision to transfer Polyperchon as far as possible from the main army. Accordingly, in 324, after campaigning with Craterus in the Indus valley, Polyperchon was ordered to return to Macedon. Thus, along with Craterus, Polyperchon began his march back into Macedon at the lead of 11,500 veterans. Most of these veterans were discharged following the mutiny at Opis. The discharged were still on their way to Macedon, in Cilicia, in June 323, when the news of the emperor’s demise reached them. Soon, the war in Europe broke out with many Hellenic cities led by Athens rising against the Macedonian rule.

Lamia, Triparadeisos, Pella

Polyperchon was among those who helped Antipater, governor of Macedon, quell the Greek rebellion in the so-called Lamian War (322-321). In 321, Antipater was confirmed as regent over Europe at Triparadeisos Conference. Another important decision made at the conference was to recognize Adea/Eurydice as the wife of King Philip III Arrhidaeus.

Within a year from Triparadeisos, Antipater succumbed to old age. The deceased had appointed Polyperchon as his successor in the regency instead of his son Cassander. Based on Polyperchon’s low profile in Alexander’s campaign, “it seems off for Antipater to choose Polyperchon as his successor to the regency and even more odd when considering Polyperchon was of the same generation of Philip [II] and Antipater, significantly older than the rest of the successors. Perhaps Antipater trusted someone from his own generation more than his son, despite Cassander being in his mid-thirties in 320, but irrespectively Cassander took serious offense…” (Alexander Meeus). Thus, Cassander began planning a rebellion to remove Polyperchon from the office at Pella. However, to avoid suspicion in revolt (apostasia), he organized a hunting trip with his friends.

Cassander Raises His Banner of Rebellion

Cassander’s hunting trip raised red flags in the Macedonian court especially considering Cassander’s no passion for hunting. To cement his authority over an unstable Macedon, Polyperchon called an assembly (synedrion) of his friends. The council decided to send a formal invitation to Olympias in Epirus, mother of Alexander the Great, offering her the regency over her grandson (epimeleia), the infant Alexander IV. In addition, Olympias was promised to live in Macedon with regal dignity (basilike prostasia), an undefined position of high political prominence.

The invitation “was a shrewd move on Polyperchon’s part, which would have given his regency for Philip Arrhidaios a little more legitimacy in the eyes of the Macedonians. The only problem was that Olympias declined, for the moment, unsure of Polyperchon himself because of his long association with Antipater” (W. L. Adams). Even better was Polyperchon’s amnesty of Eumenes of Cardia who, from an outlaw, he proclaimed regent of Asia. Eumenes’ restoration had the effect of keeping Antigonus Monophtalmus, the most dangerous enemy of the monarchy, engaged in Asia against Eumenes; preventing in this way a crossing of the “One-Eyed” into Europe.

The Diagramma

In late summer or early autumn 319, Cassander slipped away from Macedon into Asia Minor. Polyperchon, aware of this being the beginning of a revolt from Cassander against him, called another council of his friends and leading Macedonians. It was clear for all those in the council that Cassander would rely on the cities across mainland Hellas to fight the regent. Notably, Cassander could count on cities guarded by Antipater’s old garrisons or other controlled by his mercenaries, old friends, and oligarchies. As such, Polyperchon’s council decided to play a political trick on Cassander that would cut off his support at its core. The trick was a promise of freedom to all Greek cities. Envoys from Greek cities present in Macedon were summoned, likely at Pella, to whom Polyperchon formally promised the reestablishment of democracies (demokratia) in their cities. The promise was formalized into a decree (diagramma) written, of course, in the name of the kings Alexander IV and Philip Arrhidaeus.

The idea of a decree promising freedom to Polyperchon’s potential enemies was a sound one; yet, the delivery of that policy was terrible. From a promise of freedom, the document degenerated into threats and retaliation against those aligning with Cassander. Notably, as the edict sanctioned the return of those exiled during Antipater’s regency into their cities, it exempted from this amnesty the cities of Megalopolis, Amphissa (modern Amfissa), Tricca (Trikala), Pharcadon (Farkadona), and Heraclea Thracinia (Iraklia). The logic behind singling these cities out rested mostly on warfare strategy.

Reading Between the Lines

Apart from Megalopolis who had openly thrown its bid with Cassander, the other four cities were key for the control of Central Hellas. All these settlements sat on chokepoints of multiple intersecting routes threatening any army marching through them. Notably, all choke points combined controlled the routes coming from Epirus and Aetolia into north-central Hellas as well as north-south routes communicating with Thessaly, Locris, and Phocis. These were not the only cities leaning towards Cassander but Polyperchon singled them out in the decree precisely for their strategic importance.

Polyperchon made his policy worse by writing a personal letter to Argos (supportive to Cassander) after his diagramma was published. Accordingly, he ordered this city to exile all government leaders from the time of Antipater and confiscate their property. The regent in office even ordered the execution of some Argive citizens “in order that these men, being completely stripped of power, might not be able to cooperate with Cassander in any way” (Diod. XVIII. LVII. I-II). All other Greek cities understood that the fate that befell Argos on Polyperchon’s orders was a taste of what they could face. Thus, no cities across Hellas (with exceptions across Peloponnese) rallied with Polyperchon, reading between the lines the hypocrisy of the decree.

When Polyperchon marched south, away from Macedon, he left Adea-Eurydice behind in Pella. This would turn out to be a major mistake on Polyperchon’s part; free from the regent Adea-Eurydice moved her own agenda which favored the cause of Cassander. Either early on, or a year later, Adea-Eurydice issued a formal document in the name of king Arrhidaeus declaring Cassander as the new, legitimate regent.

Focus on Athens

Despite the generally poor formulation of the decree, Polyperchon could hope to turn one key city to its side with his diagramma: Athens. In fact, a splendid offer was made to the Athenians, sanctioned by the decree; the regent restored Samos to Athens but kept the independence of Oropus. This was a fine example of a “half now, half later” offer, delivering Samos but holding Oropus as a reward for Athenian compliance. As such, lured with such promises, Athens was open to discussing terms with Polyperchon. Thus, political maneuvers focused around Athens for the rest of 319 and early 318. For the Athenians, this was a good opportunity to get rid of the Macedonian garrison (Munychia) in their city.

In early 318, Nicanor (Cassander’s appointed commander) increased the numbers of his mercenary force at Munychia. This action angered some Athenians who came to favour Polyperchon. An Athenian envoy asked the assistance of Polyperchon, in accordance with his issued decree, against Nicanor; meanwhile, Nicanor seized Piraeus and the harbour boom to ease Cassander entrance here. Polyperchon could not respond with force to Nicanor’s actions as he was having difficulties coming into Attica. However, by March, Polyperchon, with the possible aid of Olympias, had stirred the politics in Athens; enough for its assembly to put in office a new group of radical democratic magistrates. The new government, favouring Polyperchon’s cause, condemned with exile or execution the previous officials of whom most prominent was Phocion.

Phocion’s “Trial”

Phocion with his party appealed in person to Polyperchon, at that time stationed near Pharygai in Phocis. Yet, Polyperchon met their appeal with utmost disrespect, interrupting Phocion and favouring the other envoy sent by radical democrats of Athens led by Hagnonides. Phocion and his followers were sent under guard in Athens, when, with the approval of Polyperchon, they were ultimately executed in early May. The treatment of Phocion’s party revealed the length at which Polyperchon would go to ensure the support of the Athenians and every other city. Instead, with his radical approach, Polyperchon drove the swinging cities further away from him.

Soon following Phocion’s execution, Cassander arrived in the Piraeus with 35 ships and 4,000 soldiers, courtesy of Antigonus. On this news, Polyperchon hurried his march and arrived in Attica with 20,000-foot soldiers, 4,000 allies, 4,000 cavalrymen, and 65 war elephants. At once, Polyperchon was faced with a serious shortage of supplies apparently caused by the northern choke points damaging his supply lines. As he could not afford to maintain a sizable army in Attica, Polyperchon took most of the forces and headed for Peloponnesus. Before leaving, the regent left his son Alexander in Attica with a portion of the army to maintain a siege over Athens.

Into Peloponnesus

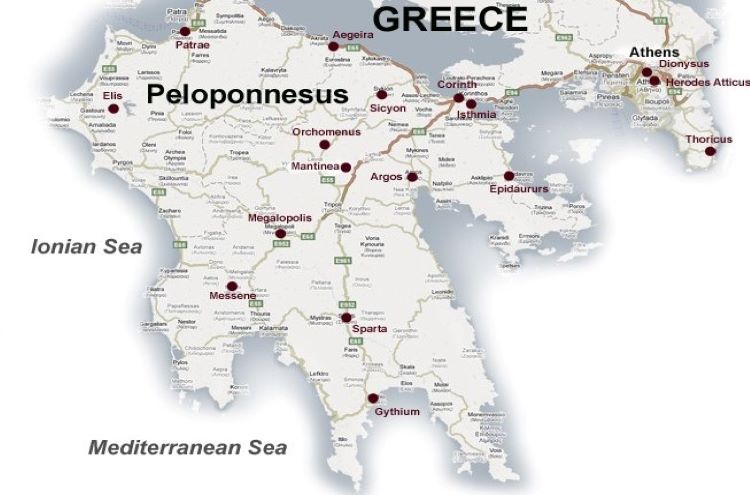

Initially, Polyperchon scored some better results in Peloponnesus. When Cassander conquered the island of Aegina and assaulted Salamis, Polyperchon called an assembly of the cities across Peloponnesus to discuss the alliance. Most of the cities responded positively, sending delegates into the assembly which meant they were open to working with the regent. Yet again, Polyperchon precipitated the situation by issuing harsh orders such as the execution of magistrates appointed by Antipater and the establishment of governments (“autonomy”) against Cassander. Many cities, with the exception of Megalopolis, went forward with the orders; massacres took place, mass exiles, and government collapse in favor of pro-Polyperchon’s establishments. This gave Polyperchon’s warfare momentum in Peloponnesus but further tarnished his figure and reputation.

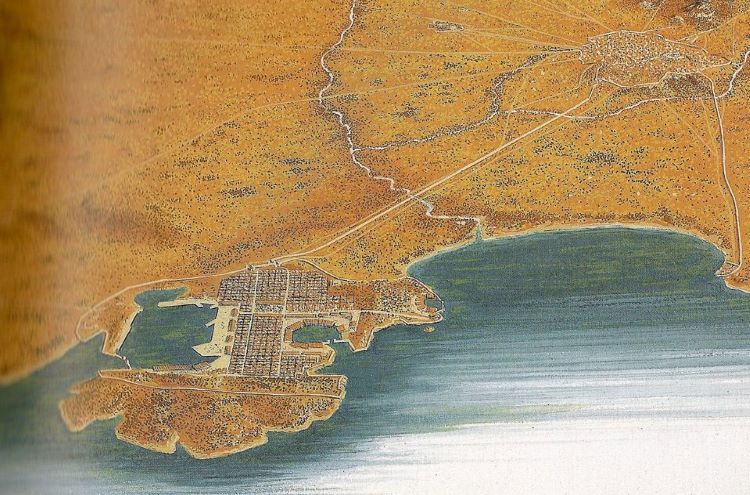

The next natural target of Polyperchon was Megalopolis. He besieged the city with his main army, building two fortified camps, wooden towers, and a palisade. His sappers dug out tunnels causing the fall of three great fortifying towers and the intersecting wall. It was at this gap where the fighting concentrated with the Megalopolitans putting out great resistance. Those defending the city acted by “cutting off the area inside the breach with a palisade and throwing a second wall…[they] quickly made good the loss they had suffered by the breaching of the wall”. (Diod. XVIII. LXX).

Siege of Megalopolis and a Megalopolitan Trap

In the following engagement at the same place, Polyperchon sought to pierce through the gap using all his elephants. Damis, expecting such a plan in advance, had “cleared the area of the breach, making it passable for the elephants…Indeed, by pitting his native wit against the brute force of the elephants, Damis rendered their physical strength useless. He studded many great frames with sharp nails and put them in shallow trenches, concealing the projecting points over them he left a way into the city, placing none of the troops directly in the face of it, but posting on the flanks a great many javelin throwers, bowmen, and catapults. As Polyperchon was clearing the debris from the whole extent of the breach and making an assault through it with all elephants in a body, a most violent thing befell them. There being no resistance in front, the Indian mahouts did their part in urging them to rush into the city all together; but the animals, as they charged violently, encountered the spike-studded frames. Wounded in their feet by the spikes, their own weight causing the points to penetrate, they could neither go forwards nor turn back because it hurt them to move. At the same time some of the mahouts were killed by the missiles of all kinds poured upon them from the flanks, and others were disabled by wounds and so lost such use of the elephants as the situation permitted. The elephants…wheeled about through their friends and trod down many of them. Finally..the elephant that was the most valiant and formidable collapsed, of the rest, some became completely useless, and others killed many of their own side”. (Diod. XVIII. LXXI).

Bad News Travels Fast

Polyperchon’s grandiose attempt to capture Megalopolis concluded this in a failure; for Polyperchon it was a disaster, his ultimate in the fight for the crown. At the siege of Megalopolis Polyperchon lost most of his soldiers with others who survived deserting him. The news of his decisive loss made the cities across Peloponnesus and the whole of Hellas abandon Polyperchon’s cause. They preferred to enter instead into the alliance of Cassander, the one who was looking more like the winner.

Even the radical democratic government of Athens sponsored by Polyperchon opened negotiations with Cassander. They eventually came to terms with him with no mass massacres or exiles instigated; a stark contrast with Polyperchon’s radical treatment in Phocion’s case. Cassander even promised the delivery of Munychia and Piraeus to the city once the war with Polyperchon would conclude.

Soon after his failure at Megalopolis, Polyperchon’s whole fleet led by Cleitus the White was vanquished in the Hellespont; again courtesy of Antigonus coming to the aid of Cassander’s fleet. Polyperchon’s defeat was now complete.

The military disaster at Megalopolis and the loss of the whole fleet at Byzantium turned Polyperchon from a favorite contender into a challenger. This change of circumstances demanded alternative solutions and Polyperchon sought them away from Europe.

An “Obscure” Asian Gamble

The movements of Polyperchon following his utter defeat in Megalopolis remain obscure but an inscription from Nesos offers some hindsight. Reconstructing a narrative from the fragmented Nesos decree, Polyperchon began preparing for an expedition in Asia Minor after his failure at Megalopolis. Accordingly, the regent departed on the eastern coast of the Aegean Sea in early 317; after spending the winter preparing the necessary forces. With this expedition, Polyperchon sought to deliver on his promise made to Eumenes of Cardia in 318 to come to his support with the royal Macedonian army (or what was left of it).

At the time, Eumenes was tarrying in Cilicia, gathering forces from wherever he could to build an enough large army to fight Antigonus. “Maintaining the alliance with Eumenes, and by extension, the alliance with Olympias was vital to Polyperchon’s efforts against Cassander and could not be placed at risk. Supporting Eumenes was fundamental to gaining Olympias’ trust and support. Polyperchon may have gambled on Cassander’s attention being focused on a hostile Polepponesus, where he would expend his military efforts in an attempt to secure the region during the time that Polyperchon was absent from Europe” (Evan Pitt).

Polyperchon’s Asian gamble did not pay off, however, as, during Polyperchon’s absence, Cassander did not invest in Peloponnese. Rather, the son of Antipater made his first venture into Macedon, a diverse move intended to, among others, alarm Polyperchon and draw him into Europe. With this move, Cassander was too delivering on the promise made to his key ally Antigonus on keeping Polyperchon engaged in Europe. Some additional bonuses Cassander earned during the Macedonian campaign were the capture of many of Polyperchon’s elephants that had survived the siege of Megalopolis and the confirmation of the title of regent to him in person by the queen Adea/Eurydice (and king Philip Arrhidaeus).

Olympias Steals the Show

After returning to Europe, Polyperchon tried to convince Olympias to throw her lot in the conflict. In the fall of 317, Alexander the Great’s mother moved with an army from Epirus into Macedon having herself involved in the European contest. Upon entering Macedon, Olympias initiated a purge among the aristocracy with notable victims the royal couple Philip Arrhidaeus-Adea/Eurydice, and Nicanor, Cassander’s brother. Polyperchon is absent in the sources and his role in these political killings of factions in favor of Cassander is unknown. It’s clear that Olympias drew the spotlights to herself moving the figure of Polyperchon to secondary importance.

At the news of Olympias return and purge, Cassander was besieging Tegea, a city in the Peloponnesus likely loyal to Polyperchon. He quickly raised the siege and moved north in Macedon to deal with Olympias. Antipater’s son was successful in keeping Polyperchon inactive. Notably, he sent his general Callas to meet Polyperchon in Perrhabeia in Thessaly. There, an engagement took place in which Polyperchon lost most forces he had levied to Callas. The regent withdrew to the fortress of Azorius where he remained safe but impotent in the war for Macedon.

Cassander besieged Olympias at Pydna, a siege that he kept during the winter of three hundred seventy/three hundred sixteen and into the spring. The city eventually surrendered after a lack of food and Olympias executed. It was during the same period when Polyperchon ally in Asia, Eumenes of Cardia, was also executed. With two of his allies now disposed of, Polyperchon had to abandon hope of returning to Macedon for the time.

Polyperchon Headquarters in Peloponnesus

After the execution of Olympias, Polyperchon went into southern Hellas where he could count on some support bases he had developed across the Peloponnese in 319-318. Polyperchon’s cause was not all lost. The termination of the alliance between Cassander and Antigonus that followed provided a major geopolitical event; an event that favored Polyperchon’s fight for Europe both directly and indirectly.

Antigonus, master of Asia, sent his officer Aristodemus to the Peloponnese to contact Polyperchon and forge an alliance with him. The alliance was materialized in three hundred fourteen as an axis against Cassander, Ptolemy, and Lysimachus. “For Polyperchon, this newly forged link to [Antigonus] Monophthalmus provided him with a vital lifeline to continue the war against Cassander from his stronghold in the Peloponnese”. (Evan Pitt)

Yet Again in Peloponnesus

After consolidating his power over Macedon, Cassander immediately prepared an invasion of the Peloponnese. Polyperchon, though seriously diminished in authority, represented a real and constant threat to Cassander’s authority in Europe. In the second half of 316, Cassander marched south. Polyperchon had stationed his son Alexander to guard the isthmus that linked the Peloponnese to mainland Hellas. Cassander bypassed Alexander’s position by approaching the Peloponnese through the sea. At the time, Polyperchon was stationed in friendly Aetolia, away from the theatre of war. This made his son Alexander the only opposer of Cassander in the Peloponnese in possession of an army.

Cassander moved on causing serious harm to Polyperchon’s influence in the region. The new ruler of Macedon conquered in succession Argos, the cities of Messenia (apart from Ithome), and Hermionis. Alexander maintained his position in the isthmus avoiding an engagement with the superior Cassandreian army in the open field. Thus, Cassander stationed two thousand men near Megara to guard against Alexander’s forces on the isthmus before returning north.

It was after this campaign when Polyperchon had some relief by signing the alliance with Antigonus. To ensure this precious support, he seems to have relinquished his authority and claim over the regency of Macedon. In return, Antigonus received recognition from Polyperchon for his authority over Asia and any future gain he could win in Europe. Aristodemus brought Polyperchon back in the game by supplying him with 8,000 mercenary troops acquired from Sparta.

A Family Betrayal

Cassander tried to turn Polyperchon to his side, away from the new alliance with Antigonus. Polyperchon refused the offer that he apparently deemed as providing less authority than the office of strategos of the Peloponnese offered by Antigonus. Shortly after Polyperchon’s rejection, Cassander launched yet another invasion of the Peloponnese. Again, the campaign achieved some success by raising the port of Corinth and nearby agricultural areas, capturing Orchomenus in Arcadia, and threatening Polyperchon’s position at Messenia. Even though this was an opportunity to put a final strike to Polyperchon, Cassander did not invest in Messenia and rather moved on to Argolis. Then, Antipater’s son returned to Macedon with expanded influence but again without succeeding in knocking over Polyperchon.

As such, Cassander sought non-military ways to deal with the Peloponnesian support towards Polyperchon. He approached Polyperchon’s son Alexander and convinced him to desert his father and join the cause of Cassander. This delivered a serious blow to Polyperchon, a threat that he endured only because Alexander was killed shortly after in Sycion. Alexander’s widow, Cratesipolis maintained loyalty towards the faction of Polyperchon and Antigonus, delivering them the cities of Sicyon and Corinth. “Other towns now gave up their alliance with Cassander, and in 313, large parts of the Peloponnese were in Antigonus’ hands. Cassander was now forced to open negotiations, which led to nothing”. (Livius.org)

The Final Act

In the autumn of 311, a peace was signed between the successors; Cassander and Ptolemy on one side and Antigonus on the other. At the same time, Antigonus distanced himself from Polyperchon. Cassander used the short peace that followed to trigger another war by murdering Roxanne and Alexander IV. To keep Polyperchon engaged, Antigonus sent to him Heracles, Alexander the Great illegitimate son with Barsine.

At first Polyperchon used the boy to claim the throne, thus pressuring Cassander into negotiations. Eventually, Cassander convinced Polyperchon to kill both Heracles and Barsine in return for the command of the Peloponnese. The disposal of the last potential heir of Alexander the Great marked Polyperchon’s final act in the course of a blundering career. Polyperchon continued to commande affairs in the Peloponnese until at least 304 when he was last recorded.

Bonus Material: Full Version of the Diagramma

As transmitted by Diodorus based on Hieronymus of Cardia who likely copied it directly from the Macedoanian royal archives.

“…peace for you and such governments as you enjoyed under Philip and Alexander, and that we permit you to act in all matters according to the decrees formerly issued by them. We restore those who have been driven out or exiled from the cities by our generals from the time when Alexander crossed into Asia; and we decree that those who are restored by us, in full possession of their property, undisturbed by faction, and enjoying a complete amnesty, shall exercise their rights as citizens in their native states; and if any measured have been passed to their disadvantage, let such measures by void, except as concerning those who had been exiled for blood guilty of impiety in accordance with the law. Not to be restored are the men of Megalopolis who were exiled for treason along with Polyaenetus, nor those of Amphissa, Tricca, Pharcadon, or Heraclea; but let the cities receive back the other before the thirteenth of Xanthius [April]. The Athenians shall possess everything as at the time of Philip and Alexander, save that Oropus shall belong to its own people as present. Samos we grant to Athens, since Philip…also gave it to them. Let all the Greeks pass a decree that no one shall change either in war or in public opposition to us, and that if anyone disobeys, he and his family shall be exiled and his goods shall be confiscated. We have commanded Polyperchon to take in hand these and other matters. Do you obey him, as we also have written to you formerly; for if anyone fails to carry out any of these injunctions we shall not overlook him”. (Diod. XVIII. LVI).

Bibliography

Adams, W. L. (1993). Cassander and the Greek City-States (319-317 B.C.).

Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica.

Livius.org. (2002). Polyperchon. Retrieved from: https://www.livius.org/articles/person/polyperchon/.

Lyngsnes Ø W. (2018). The Women Who Would Be Kings. Trondheim.

Meeus, A. (2009). Kleopatra and the Diadochoi. PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – WALPOLE, MA.

Meeus, A. (2012). Polyperchon. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. pp. 5398–5399.

Pitt, E. (2016). The Contest for Macedon: A Study of the Conflict Between Cassander and Polyperchon (319-308 B.C.).

Sverkos, I. K. (2010). Macedonia in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods.