Adea Eurydice: The Teen Queen Who Shook an Empire

Adea Eurydice was born sometime between 338-335 B.C.E., to Amyntas IV, son of Perdiccas III, and Cynane, daughter of Philip II’s wife, Audata. She grew up without a father since, soon after birth, the newly crowned king Alexander III had Amyntas executed. Her mother Cynane, herself of Illyrian origin, dealt carefully with her education. Adea’s lessons, unlike those of other female royalty, focused on martial prowess as much as on courtly manners.

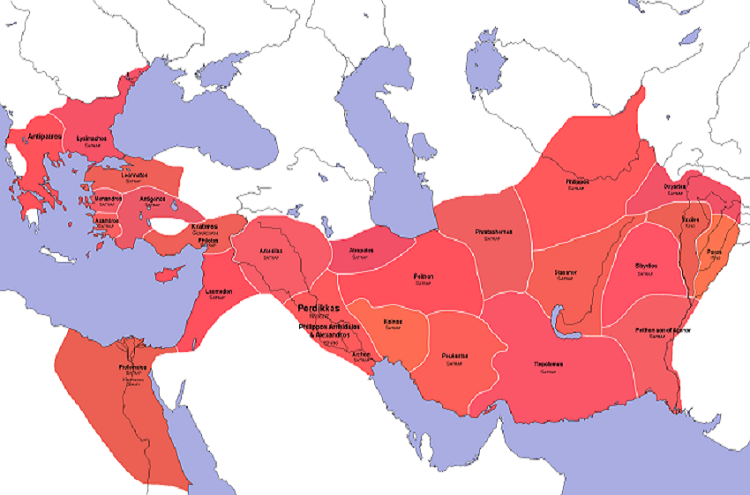

Adea’s Position in the Wars of Succession

Like many others, Adea entered the theatre of political history after Alexander the Great’s demise in 323. Her mother became her fierce advocate, pushing her claims for the Macedonian throne. At that time, Adea and her mother could only count on each other, having no allies in any of the Successors. On the contrary, they were the common enemies of all-powerful successors such as Perdiccas, Antipater, and Antigonus. They were also the opposing branch of the other Argeads such as Olympias and her daughter Cleopatra.

Cynane, and by extension Adea, may have held a grudge against the Alexandrian line of the Argeads. After all, Alexander had killed Cynane’s husband upon his accession. Cynane was aware of another important event: the Macedonian army had forced the generals to appoint Alexander’s brother Philip Arrhidaeus and Alexander’s infant son Alexander IV as joint-kings. Cynane, herself approaching menopause, intended to marry her daughter Adea to the new king Arrhidaeus.

A Queen’s Sacrifice

After the conclusion of the Lamian War, Cynane gathered an army and began marching towards Sardis taking the teenage Adea with her. Cleopatra, daughter of Olympias, had already reached Sardis where all the political action was. Antipater could not afford another “Cleopatra” easily reaching Sardis. Thus, he gathered a force and tried to stop Cynane and Adea from crossing the river Strymon near Amphipolis. Despite the blockade, “...Cynane crossed the Strymon, forcing her way in the face of Antipater…” (Pol. VIII. LX).

Cynane and Adea eventually reached the plain of Sardis where another force met them. It was a large royal army led by Alcetas, brother of the then imperial regent Perdiccas. Alcetas ordered Cynane to turn back but the headstrong queen refused. Then, “Alcetas…advanced to give her battle. The Macedonians at first paused at the sight of Philip’s daughter, and the sister of Alexander; but after reproaching Alcetas with ingratitude, undaunted at the number of his forces and his formidable preparations for battle, she bravely advanced to fight against him”. (Pol VIII. LX).

In the following, unusual duel, Alcetas slaughtered Cynane himself. Disgusted and shocked from the murder, the soldiers of both armies mutinied and demanded that the deceased’s will be fulfilled; Adea had to marry Philip Arrhidaeus. The mutiny forced Perdiccas to allow the marriage. The marriage between Adea and Philip Arrhidaeus took place either in Sardis or on the road to Syria, in 321.

A Teen Queen

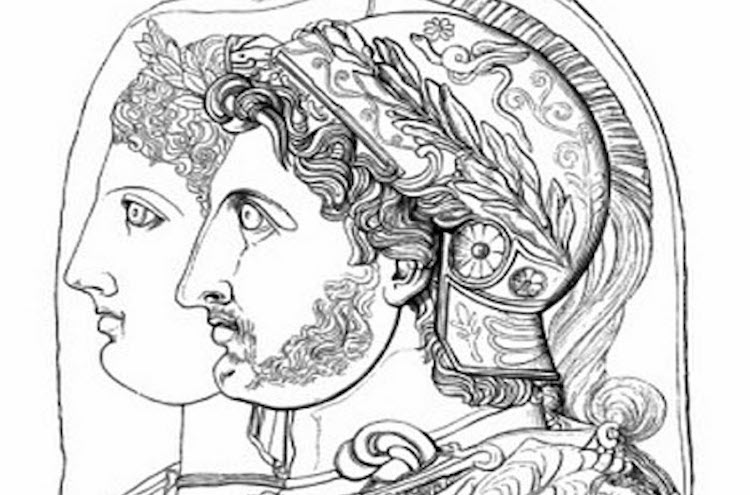

Either upon marriage or soon after, Adea took the new name Eurydice, invoking the memory of her great grandmother (Philip’s II mother), Eurydice I. This change sought to appeal to the Macedonians and promote the idea of an energetic queen in charge. Hereafter, Adea appears in contemporary sources simply as Eurydice. Meanwhile, scholars in general refer to her as Adea-Eurydice.

The imperial queen joined the royal army on their way to Triparadeisos, the place of a conference between generals. The main issue of concern was the election of a regent to succeed Perdiccas. On the road to Triparaidesos, Adea, vested with queenship, forced Peithon, the temporary commander of the royal army, to pass every major decision through her. This made it clear that the queen, even only a teen, would try to steer things her way. None of the successors could let this happen.

Marriage with Philip Arrhidaeus put Adea/Eurydice into a unique situation. The king, although an adult, suffered from a mental and physical deficiency since birth. Thus, Adea could easily manipulate the king, using his authority and legitimacy to address the citizens, army, and other players. She could, and in effect did, further her own ambitions using Arrhidaeus’ signature to sanction her actions.

Adea hoped that Arrhidaeus could also serve another role; that is to produce her an heir. Due to his handicap, we may believe Philip Arrhidaues could not produce an heir. During the four years, the couple spent married no author reports Adea bearing or giving birth to a child. This significant drawback intensified the young queen’s desire to tend to the military ways more than diplomatic solutions.

Fury at Triparadeisos & Return to Macedon

At Triparadeisos, the generals unofficially separated the empire between them. They also elected Antipater as the new imperial regent, thus custodian to Arrhidaeus and Adea, as well as infant Alexander IV. After these decisions, Adea stunned the Diadochi by appearing in front of the royal army and making a fiery speech in support of the royalty. Her speech so agitated the troops listening that they mutinied on the spot. They even tried to kill the newly appointed regent Antipater, as well as Antigonus and Seleucus when they came to the regent’s aid. The Diadochi managed to escape the chaos and quell the rebellion.

Every participant at Triparadeisos realized that Adea had to be kept in check. She had just shown she could make use of any political platform and her status to her own interests. What’s more remarkable was that she had incited a mutiny by having virtually no allies among the Macedonian ranks. The sources mention only a certain Asklepiodoros, the army’s secretary (grammateos), and one Attalus, probably a Perdiccan loyalist, as supporting her cause. Yet, even his support seems circumstantial rather than calculated. The queen needed an important ally if she ever hoped to rule over Macedon on her own will and continue her own line of succession. She would find such an ally in the figure of Cassander.

From Triparadeisos onwards, Antipater kept Adea in check though his measures remain unknown. The regent brought the imperial couple and young Alexander IV from Syria back to Macedon. Yet, not long after arrival into Macedon, in early 319, Antipater succumbed to poor health. His will was a strange one: Polyperchon inherited the regency position instead of Antipater’s own son Cassander.

Alliance with Cassander

Adea was now loose from the one who curbed her attempt at gaining significant power at Triparadeisos. However, the appointment of Polyperchon as her custodian was equally discouraging. The latter belonged to the same generation as his predecessor and tended towards keeping the Adea-Arrhidaeus couple in check. However, Polyperchon was a weak politician and commander compared to his predecessor in office, Antipater. This provided Adea with an ideal opening to further her policy. Her policy must have been a continuation of her deceased mother’s: eliminate the remaining members of the Alexandrian branch of the Argead and secure her great grandfather Perdiccas III line of succession.

Disinherited from the regency, Cassander found in Adea his source of legitimacy. Adea and Cassander seem to have approached each other since 319, both being presumably at court in Pella. They spent more than a year in the same place, enough time for both of them to realize that they could assist each other in their ambitions. From the literature available, we can assume their alliance was based on their common interests as well as common enemies. To be noted is Cassander’s hate for the Alexandrian line of succession and especially his despise for Olympias, Adea’s main Argead rival.

According to Orossius, Adea’s alliance with Cassander was based on the latter’s sexual lust for the young queen. This remark is, albeit exotic, problematic. Firstly, Orossius wrote seven centuries after the events of our concern. His work is not immune to errors. Secondly, the remark is part of the work he titled “Histories Against the Pagans” (“Historiae Adversus Paganos”), thus biased by default towards Adea. However, a probable ambition of both Adea and Cassander to marry each other sometime in the future remains part of the equation.

A Lost Narrative?

The alliance between Adea and Cassander may have relied on an even stronger tie. According to a narrative based solely on epigraphic evidence, Cassander married Adea’s younger sister in 319. This unrecorded sister bore the name of her mother, Cynane. The marriage with Cynane II gave Cassander a daughter named Adea as her aunt, and a son. This daughter did not survive infancy but Cassander’s son would later become Philip IV who ruled Macedon for a couple of months in 297. This narrative would turn the alliance between Adea and Cassander into an alliance between in-laws. This would explain Adea openly siding with Cassander since the start of his rebellion without even waiting on its outcome.

The sources are unclear as to who initiated the alliance Adea-Cassander. According to Justin, “Cassander, attached to her [Adea] by such a favor, managed everything according to the will of that ambitious woman”. (Justin, XIV.V.IV) The favor mentioned refers to Adea appointing Cassander as the regent on behalf of king Arrhidaues. As such, we have Adea commanding the dynamics and Cassander following a pre-arranged plan of action. This makes Adea/Eurydice the mastermind behind the civil war that swept European Macedonian where Cassander and Polyperchon fought for the same seat.

Cassander Appointed New Regent

In 319, Cassander started his rebellion against Polyperchon by getting Greece on his side. Polyperchon left Macedon and went south to fight Cassander. The latter made the mistake of leaving Adea and Arrhidaeus behind in Pella rather than bringing them with him on the campaign. Free from the regent, Adea could freely and more broadly express her political will. She sent letters to the supreme commander (strategos autokrator) Antigonus officially asking him to recognize Cassander as the legitimate regent rather than Popyperchon. Antigonus who sought to advance his own interests, accepted Cassander’s claim to regency and viceroyalty as pressed to him by Adea. He even sent Cassander some 4,000 troops and a significant naval force. The young queen even sent letters to Polyperchon, ordering him to resign from the regency position. Ultimately, Adea sent letters to Cassander confirming him the regency on behalf of king Arrhidaeus.

Adea made sure all the letters bore the credentials of Philip Arrhidaeus but all knew Adea was the real author. However, the king Arrhidaeus’ signature made the content and orders on the letters legally binding, at least as far as Adea and Cassander were concerned. Moreover, Cassander was winning the war against Polyperchon, both on land and on the sea. Cassander’s control of Athens was especially meaningful. Cassander could even afford to leave his campaign on hold when he made a quick visit back into Macedon during the summer of 317. There, Adea, on behalf of herself and her husband Arrhidaeus, confirmed to him the regency in person. The newly appointed regent had to quickly return south where Polyperchon was again threatening his gains.

Olympias

Polyperchon had made one crucial move to Adea’s detriment: since early 318 he had offered Olympias, Alexander the Great’s mother, the role of royal superintendence (epimeleia) of her grandson Alexander IV as well as a position of high authority and prominence (basilike prostasia). Olympias has spent more than a year thinking about the offer, back in Epirus. Apparently, the queen-mother felt the moment to act had come when Cassander was winning his war and Adea had gained the capacity to kill her, Alexander IV, and all Alexandrian line.

In the fall of 317, Olympias led an army back into Macedon from Epirus. Aeacides, her nephew, king of Epirus, supported her with most of the contingent. In Macedonia, “when Eurydice [Adea], who had assumed the control of the regency, heard that Olympias was making preparations for a return, she sent a courier into the Peloponnese to Cassander asking him to come to her aid as soon as possible; and by approaching the most important of the Macedonians with gifts and great promises, she attempted to make them loyal to her person”. (Ibid. IXX. XI. I-VI). In time of Adea’s correspondence, Cassander was engaged far south in Tegea, Peloponeese.

Adea, thus, as Olympias, gathered a large army, possibly recruiting what she could among the deserters of Polyperchon’s original force. For a queen no more than twenty-one years old, assembling and leading a force was quite an astonishing undertaking.

Assessing the Situation

Adea knew that her position as a regent queen was secure as long as Olympias would not get custody of Alexander IV. Under Olympias, the latter would grow up to outrank Philip Arrhidaeus’ authority, and by extension, the authority of Adea. Olympia’s success could eventually lead to the execution of both Arrhidaeus and Adea, promoting Alexander IV as a sole ruler. In geostrategic terms, Adea also knew that she had to physically stop Olympias and Aeacides from getting custody of Alexander IV; essentially she had to keep Polyperchon, who had Alexander IV with him, and Olympias apart. In fact, it seems that Polyperchon had arrived in Pydna with the infant king in his company. Pydna’s closeness to Adea’s-controlled Pella, as well as Olympias’ approach towards Pydna, increased the discomfort of Adea.

Adea did not wait for Cassander’s arrival with reinforcements, either because she did not believe it would happen in time or either because she felt an urge to make a warrior-like appearance on the battlefield. The latter reasoning falls in line with Adea’s character. According to O.W. Lyngsnes, “Adea was motivated by her desire to be portrayed as a warrior-queen. Just as Olympias’ heroic ancestors was a cornerstone of her personal identity, so too was the Illyrian warrior and military culture important to Adea…”.

A “Symbolic” Battle

Adea set forth with her troops and met the Olympias-Aeacides’ force in Euia, an unidentified location in Dassaretis (current southeast Albania). Duris of Samos called it the first war between women, although hardly any combat took place. The stand-off came down to a clash of symbols rather than fighting might.

Olympias appeared on the battlefield dressed as a Bacchant, playing on Macedonian fond of the Dionysiac cult as well as her distinguished descent. On the other hand, “Eurydice [Adea] came forward clad like a Macedonian soldier, having been already accustomed to war and military habits in the household of Cynane the Illyrian” (Duris of Samos). If Adea could demonstrate military leadership, dressed as a male phalangite, she could claim competence over this male-dominated activity.

Yet, Adea had not rightly assessed Olympias’ influence among the Macedonians. All Adea’s troops knew Olympias while hardly anyone from the Olympias’ Molossian ranks knew Adea. Ultimately, most of Adea’s army defected to Olympias, leaving Adea and Arrhidaeus running for their life.

Execution

Eventually, Olympias’ army caught and killed Arrhidaeus and imprisoned Adea/Eurydice. Diodorus wrote that Olympias gave Adea a choice between a noose, a sword, and a goblet of poison for her to kill herself.

The teenager refused Olympias instruments and hung herself with her own belt in a tragic scene strangely similar to Antigone in Sophocles’ “Antigone”. Such was the fate of Adea/Eurydice. Her execution, forced or not, completed the destruction of the Perdiccan line of the Argeads.

Bibliography

Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica.

Justin, M. I. Epitoma. Historiarum Philippicarum. Pompei Trogi.

Lyngsnes Ø W. (2018). The Women Who Would Be Kings. Trondheim.

Meeus, A. (2009). Studia Hellenistica. Kleopatra and the Diadochoi. PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – WALPOLE, MA.

Whitehorne J. E. G. (1994). Cleopatras. Routledge, 2001.