Dyrrachium: Port & Gateway between West & East

Dyrrachium (or Dyrrhachium) refers to the ancient city that flourished on the territory of the current coastal city of Durrës in Albania. The name is formed by the root “Dyrrach” followed either by the typical Latin suffix “ium”. Before appearing in Latin sources it appeared in ancient Greek literature as “Dyrrachion” (“Dyrrach” + the typical ancient Greek suffix “ion”). In the Albanian language, it appeared as “Dyrrah” and then, since the Middle Ages, as “Durrës”. During the Middle Ages, the city was ruled for a long time by the Venetians who referred to it as Durazzo.

Early History

Appian tells us the tale of Dyrrachium’s foundation. According to him, a barbarian king of the region with the name Epidamnus founded the city. Dyrrachus, his nephew and son of Neptune, added a dockyard to the city, and named this after himself, Dyrrachium.

Dyrrachium was established from colons coming mainly from Corcyra and some from Corinth. Rather than a proper foundation it was a seizure of an already present Liburnian/Illyrian settlement. The traditional date of this foundation is the year 627 B.C.E. According to Thucydides, a certain Phalius, son of Eratocleides from Corinth of the family of the Heraclids, was the first leader of the new colony.

The new colony was named Epidamnus and developed on top of an already present Illyrian/Liburnian settlement called by ancient Greeks Dyrrachion/Dyrrhachion. Eventually, the name Dyrrachion continued to be used for the upper part or the dockyard of the colony while early literal evidence referred to the colony in general with another name, Epidamnos or Epidamnus. Numismatic evidence shows the name Dyrrachium since the IV-th century B.C.E. Thus, the names “Epidamnus” and “Dyrrachium” must have been used interchangeably to refer to the same settlement, at least during the period before the Roman invasion. When the Romans entered the scene they abandoned the name “Epidamnos” as a sign of bad omen (damnus meant “doomed” in Latin) keeping “Dyrrachium” as a sole name.

The population of Dyrrachium (and nearby Apollonia) experienced a substantial population increase sometime around 575. This was because of other colons/migrants coming from the destroyed Dyspontion, in Peloponnesian Elis. Usually, newcomers into an established colony were not awarded the same rights and honors as the families of older colons. Yet, this was more the case with Apollonia rather than with Dyrrachium. The latter hosted a somewhat heterogeneous population made up of Corinthians, Corcyraeans, other Doric tribes, and Illyrians.

It quickly became an important port and commercial town. The colons initially established an oligarchic constitution significantly dependent on its direct metropolis Corcyra and indirect metropolis Corinth. Trade with the neighbouring Illyrian tribe, mainly with those occupying the immediate hinterland, the Taulantii and the Parthini, brought economic prosperity to the city. The colony could even afford to erect a treasury at Olympias (Pausanias, VI. IXX. VIII).

The period from VI-th century to the second half of the V-th century was a period of economic prosperity. It’s interesting to mention that during this period, the city did not find the need to mint its own coins. Rather, its traders made use of coins from the metropolis of Corcyra and Corinth, where most of the commerce was already focused.

Civil War & Peloponnesian War

The colony initially established institutions similar to those of other Hellenic colonies. It consisted of an oligarchic system ruled by a phylarch (elected commander from the collective tribes of the colony). According to Thucydides this system was not preferred by the heterogeneous population of the city. Thus, in 446/445, the people expelled the oligarchs from the colony, an action that sparked a civil war. The inner conflicts then involved the Illyrians of the hinterland, as well as Corcyra, Corinth, and Athens, becoming one of the main triggers of the Peloponnesian War.

The Corcyraeans eventually came up on the winning side in a long war that concluded in 411. This reestablished the oligarchs into Dyrrachium but now the city had lost its prosperity. During the Peloponnesian War, Dyrrachium remained paralized, blocked from the sea by the Corinthian colony and by land from the Illyrians and the expelled oligarchs that had found refuge among these Illyrians. At the epilogue of the war the Corinthians “forced the surrender of Epidamnus”, executed all the captives “except the Corinthians, whom they cast in chains and imprisoned”. (Diod. XII. XXXI).

Recovery & New Constitution According to Aristotle

In the next century there is a lack of Dyrrachium in literal evidence. It appears that the city went through a slow recovery by relying again on sea-borne commerce. In the IV-th century, the city issued its own autonomous coins breaking its monetary ties with Corcyra and Corinth. Moreover, the coins bear the anagram “DYP” for “Dyrrachium”. This shows the presence of the name Dyrrachium among the locals some three hundred years before it comes up again in literal evidence.

Aristotle (384-322) tells us of important changes made in the constitution of Dyrrachium either in the period following the Peloponnesian War or in Aristotle’s own period. The oligarchic institutions of the pylarch were replaced by a more representative body, the “boule” or the city council/parliament. Also, it seems that during this same time, the governance from an archon (sole ruler) was abandoned/abolished. Aristotle further adds that in the collective meetings of the people it “is still compulsory for the magistrates alone of the class that has political power to come to the popular assembly when an appointment to a magistracy is put to the vote” (Aristotle, Politics, V, section 1301, b). The author also suggests Dyrrachium (which he calls Epidamnus) as an ideal model when it comes to using slaves for constructing major public works. In Aristotle’s time it seems that the city was inhabited roughly as much from Illyrians as from Hellenes. The difference seems to have been in that the Illyrians had no right to hold governing offices.

Macedonian & Illyrian Threats to its Autonomy.

In the early Hellenistic era, notably in 314, the Macedonian king Cassander defeated an Illyrian force of king Glaucias somewhere near Dyrrachium. He then captured the city by a stratagem. Cassanders’ rule here was brief. Only two years later, the Illyrians in cooperation with the Corcyraeans and the citizens of Dyrrachium drove out the Macedonian garrison of Cassander. After the liberation, Corcyra awarded the dominion of Dyrrachium to Glaucias.

Dyrrachium continued to remain under the control of the Illyrian state of the Taulantii/Parthini in the Hellenistic era. Illyrian kings Monunius (r. 300-272) and Mytilus (272-260) seem to have had control over Dyrrachium. This period corresponds with a large increase in the Illyrian element on the demographic composition of the colony. Archaeological evidence supports this claim. Moreover, the penetration of Illyrian elements was so significant that it affected the political institutions of the colony. These institutions, although evolving in a Hellenic fashion, also “developed in response to the internal social evolution of the Illyrian peoples”. (N.G.L. Hammond, The Kingdoms in Illyria Circa 400-167).

The autonomy of Dyrrachium was threatened by the expansion of the Illyrian state of the Ardiaei. Their queen Teuta was close to capturing the city in 229, but the interventions of the Romans prevented her success. After the First Illyrian War, the Romans established their rule over the city. Yet, Roman Republicans allowed the citizens a significant degree of autonomy designating it as a “civitas libera” (free city).

War Between Caesar and Pompey at Dyrrachium

The city was of strategic and economic importance to Rome; it was the most convenient port for ships coming from Italy, usually from Brundisium. Also, here started the main route that connected the Adriatic and Aegean Sea. On this route the Roman constructed an important road network during the first century C.E., the famous Via Egnatia. It started from Dyrrachium, received a branch coming from Apollonia, and then arrived into Thessalonica and then into Byzantium. It was for its strategic position that Dyrrachium played an important role during the civil war between Caesar and Pompey.

On march 59, at the height of the civil war, Pompey and his followers (including many Roman senators) left Italy and arrived in Dyrrachium. The Adriatic turned into a division line between the Caesareans and the Pompeians. Caesar followed his enemy with half of his projected army (five legions) by landing somewhere south of Dyrrachium, near Oricum. Without waiting the rest of his army commanded by Marc Antony, Caesar took fast the cities of south Adriatic, Oricum, Apollonia, and Bylis. However, his forces could not arrive in time to capture Dyrrachium.

Pompeian forces blocked Caesar’s advance in the Apsus (Seman) River. Dyrrachium was a key objective for ensuring a continuous supply line for each army. Thus, both armies continued for months building blockades against one another near and round Dyrrachium in attempts to force the other into surrender due to famine. Eventually, Caesar tried to enclose Pompey in Petra but failed to do so. Instead, the walls of Caesar were breached near the coast and his side fled into retreat.

Caesar would eventually triumph over Pompey in Pharsalus but Dyrrachium had to pay the price for the anti-Caesarian role during the civil war. The Roman dictator ordered the citizens of Dyrrachium to pay heavy taxes, otherwise non-applicable to it as “free city”. The assassination of Caesar in 44 must have come to a relief to the Dyrrachians. During the reign of Octavian Augustus the city gained the status of a colonia.

Roman Rule

Cicero remains the first author to use only the name Dyrrachium to refer to the city (whom he visited himself), abandoning the name Epidamnus. Thus, from the civil wars of Pompey and Caesar onwards, the name Dyrrachium prevails as the sole name for the whole city.

Dyrrachium turned the main entrance into the Via Egnatia, earning important revenues from customs on cargo transports. During the first century C.E., an elaborate network of roads developed in and around Egnatia, allowing for increased trade and improved communication in the region. Quickly, Dyrrachium turned into the main port of the Adriatic. Along with Salona north, it served as the main catalysts of the early expansion of Christianity on both sides of the sea.

The early imperial period marked another period of prosperity for the city. Its infrastructure was further improved in typical Roman fashion. During the reign of Trajan (r. 98-117), a large oval amphitheater with a capacity of 15,000-20,000 spectators was built. It served the taste of a large Roman population. Once completed it revealed a sophisticated complex with arches, colonnades, tiered stairs, subterranean galleries, gates for gladiators, and the mighty arena. Little is known about the details of the fights that took place here. An inscription tells that twelve gladiator fights were held in the amphitheater to celebrate a new construction in the city, that of its library.

Trajan’s successor, Hadrian (r. 117-138) built a major aqueduct for the city, 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) long. It appears that emperor Hardian visited Dyrrachium himself, sometime in 126 C.E. It seems that during his visit, the emperor himself observed the initial works on the aqueduct. The proportion of this project reveals the large population that inhabited the city.

This was one of the most complex works of Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean including tunnels cutting though hill areas (longest: 2,700 meters or 8,858 feet) and supporting bridges stretching into lowlands. The source of the aqueduct was in the Ululeus (Erzen) River. Its waterway’s height was equal to that of Athens built around the same time, at 1.35 meters (4.43 feet), with a width of 0.99 meters (3.25 feet), only 11 centimeters (about 4 inches) less than that of Athens.

Emperor Severus Alexander (ruled 222-235) continued to invest in Dyrrachium. He financed a major reconstruction of the aqueduct built by his grandfather Hadrian. Also, Severus reconstructed at a length of four miles the road that started at Dyrrachium and continued into its hinterland, in the direction of Tirana’s plain. This road, which has not received proper attention, was a branch of the Via Egnatia, convenient for communication with current central Albania.

Byzantian Rule & Invasions

An important change occurred in 394-395 when emperor Theodosius I ordered the closure of all gladiator schools across the empire, including those in Dyrrachium. It was the same year when the Roman Empire divided into its two parts: the Western (Latin) and Eastern (Byzantine) part. The Byzantine Empire with its capital at Constantinople, included within its territories all the Balkans including Dyrrachium.

From a city at the empire’s core, it became, geographically, a peripheral city. In 404, emperor Honorius sealed Theodosius’ initiative by prohibiting any fighting from taking place in amphitheatres. This clearly diminished the role of the amphitheatre as an entertaining centre and economic stimulant. The ruins of a chapel dated to the second half of the VI-th century have been discovered in the western part of the amphitheatre.

From the IV-th century to the VI- century, Dyrrachium had to endure destabilizing invasions from the Visigoths and then Ostrogoths. The latter even invaded the city briefly in 480/481. They used it as a base to invade Italy and establish their kingdom there. Moreover, in 345, a powerful earthquake hit the region causing severe damage to the magnificent infrastructure of Dyrrachium. Yet, life in the city went on. Churches were built and bishops were installed. The city became the episcopal center and capital of the Byzantine province of Epirus Nova.

The largest efforts to improve the infrastructure in Dyrrachium after the devastating earthquake and Gothic invasion was taken by emperor Anastasius I Dicorus (491-518). The emperor, from Dyrrachium himself, founded the new Byzantine fortress of the city. It was surrounded by strong walls, with three protective layers, made with fine brick material. The fortress included the fortification with a one meter thick wall of the narrow isthmus just north of the main city. Yet again, after Anastasius, the city was hit by another earthquake, in 522. Justinian (r. 526-565) took care of the damages, completed the walls of Anastasius, and made other reconstructions.

In the early ninth century, the Byzantines established the theme of Dyrrachium, a military province focused round the city. Yet, a hundred years later, the city fell to the Bulgarian empire. It was recaptured by the Byzantines only around 1018.

Wars in Dyrrachium Between the Byzantines and the Normans

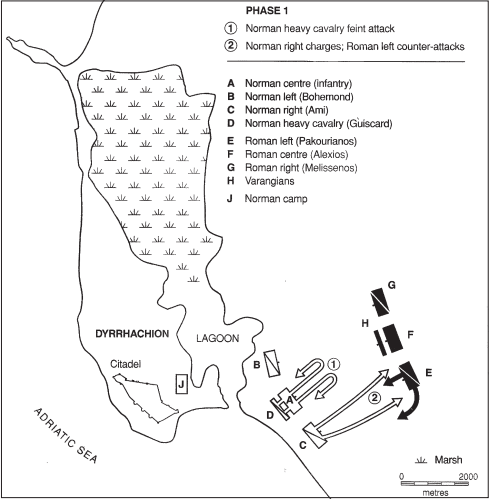

In 1081, another invasion targeted Dyrrachium, this time from the Normans of southern Italy. A large army under Robert Guiscard landed south and then reached Dyrrachium. Anna Komnene (Comnena) daughter of the then emperor of Byzantium Alexius I Comnenus, describes the event in detail in her “Alexiad”. On October 15 of that year, Alexius himself arrived in Dyrrachium with a large army and three days later began the battle against the Normans known as the battle of Dyrrachium.

The Byzantine side was eventually crushed by the Normans thanks, in part, to a decisive cavalry shock charge made by the Norman cavalry. Their cavalry men assaulted holding their lances up and ahead rather than throwing them against the enemy. The innovation was still new when introduced in Dyrrachium. It was tested before at the Battle of Hastings, but would gain more importance and weight 15 years later during the First Crusade.

After the defeat in open battle, the city continued to resist but fell to the Normans in February 1082 after a determined resistance. The fall of Dyrrachium marked the beginning of Norman conquest of the remaining part of the coast, complete in a year.

Alexius would push back against the Normans in the following years but had to enter into an alliance with the Venetians who were interested in the coastal areas of Dyrrachium and Corfu. The alliance allowed Byzantium to regain control of most Balkan territories by a 1083 including Dyrrachium.

In 1107, Bohemond I of Antioch, oldest son of Guiscard, launched another Norman expedition against Dyrrachium. This time the emperor was prepared. The Venetian fleet blocked the port while Alexius with the main army kept the enemy in check through land. The Norman camp would also suffer from a spread of typhus disease which forced them to sail away. Dyrrachium was safe.

The Destabilizing Role of the Crusades

In between two Norman invasions the city was flooded by soldiers of the First Crusade (1096). These large but undisciplined armies would put a strain on the local stability and economy. Again, Alexius took measures to protect the locals from the “trespassers” by placing food reserves and army patrols from Dyrrachium and all along the Via Egnatia. When compared to other Balkan lands, these measures helped the city and its hinterland from excessive robberies and disturbances. For the remaining years of the Comnenus dynasty, Dyrrachium was relatively safe from external threats.

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade captured Costantinople. For the next a hundred years Byzantium was run by Latin emperors. During that period also, various independent states emerged in the European possessions of Byzantium. One of those states was the Despotate of Epirus. It was established immediately after the fall of Costantinople by Michael I Comnenus Ducas, illegitimate grandson of Alexius I Comnenus. Michael established its capital in Arta (ancient Ambracia) but included within it Dyrrachium. His successor and illegitimate son Michael II Comnenus Ducas (despot of Epirus during 1237-1271) used the Despotate to fight for the imperial throne. From 1256, Michael II left his state to fight east for the possession of Costantinople. His absence was used by prince Manfred of Sicily (r. 1258-1266) who, two years later, captured Vlora, Butrint, and Dyrrachium.

In 1266, Manfred Hohenstaufen of Sicily fell in battle against the crusaders of Charles of Anjou, younger brother of king Louis of France. The Angevines took under formal jurisdiction the lands conquered by Manfred, but they still lacked military presence in eastern Adriatic. The Byzantines used the event to recapture their lands along southern Adriatic and its hinterland. The lands went back and forth between the Byzantines and Angevines. Moreover, a powerful earthquake in about 1273 caused destruction to the city. In about 1280, Charls of Anjou dispatched 8,000 troops across Albania. A rapid response from the Byzantines recaptured all Albanian lands in the following year. Yet, in 1307, the Angevines recaptured Dyrrachium.

In the next decades, the Serbs entered the scene: their king Stefan Dusan invaded Albania and conquered Dyrrachium in 1343. The Serbian invasion lacked the administrative body to control the new lands. Instead, semi-independent small states emerged across Albania, governed by local/Albanian families.

Local Governance of Karl Topia

After the demise of Dusan in 1355, the Albanian families remained as the only functional authority in the region. One of these families was the Topiaj family led by Karl Topia. His territorial authority included Dyrrachium with its hinterland. The rule of Karl Topia from 1367 to 1392 seems to have been a prosperous one. In about 1380, the theological university (Studium Generale) of Dyrrachium was created, one the the oldest in the Balkans. The university helped educate many notable figures, among them “Gjoni i Dyrrahut” (John of Dyrrachium). At the same time, the city maintained a high degree of autonomy as a “comuna civitas” and its own laws through its own statute.

Under the threat of the Ottomans, Karl Topia surrendered the city of Dyrrachium to the Venetians, in 1392. Several natural disasters, invasions, and centuries of rapid dynamics had taken their toll on the city. By this time, the Byzantine fortress was in ruins, the aqueduct vanished, and the amphitheater just an old relic. The city, once a splendid settlement, entered into its Medieval period. The Albanian name Durrës replaced that of the old Dyrrachium.

Bibliography

Cabanes, P. (2001). Historia e Adriatikut.

Hammond, N.G.L. The Kingdoms in Illyria Circa 400-167.

Heher, D. Dyrrhachion / Durrës – an Adriatic Sea Gateway between East and West.

Forsén, B, Mika Hakkarainen, M, & Brikena Shkodra-Rrugia, B. (2015). Blood and Salt: Some ThoughtsEvolving from the Topography of the Battle at Dyrrachium in 1081. ACTA BYZANTINA FENNICA VOL. 4 N. s.).

Gloyer, G. (2008). Albania: The Bradt Travel Guide.

Kasa, A. (2015). The History of Roman Durrës (I-IV E.S.). Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy.

Miraj, F. (1982). Ujësjellësi i Dyrrahut / L’aqueduc de Dyrrachium. Iliria, Nr. I.

Stephenson, P. (2004). Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204. Cambridge University Press.

Shufaj, M. (2014). Historia e Durrësit të Vjetër.

Wilson, N. G. (2006). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece.

Zheku, K. (1997). Epidamni dhe Dyrrahu në lashtësi ishin dy qytete të veçanta apo një qytet i vetëm me dy emra ? / Waren Epidamnos und Dyrrah im Altertum zwei einzelne Städte oder eine einzige Stadt mit zwei namen ? Iliria, Nr. I-II.