Buthrotum: The High & Lows of a Splendid Civilization

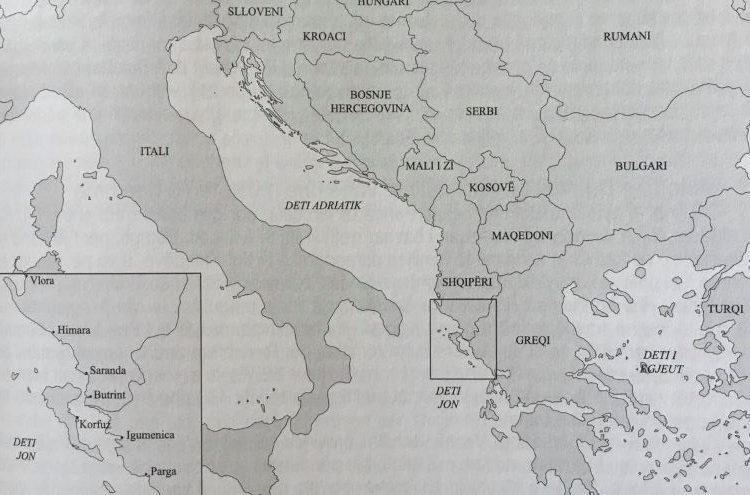

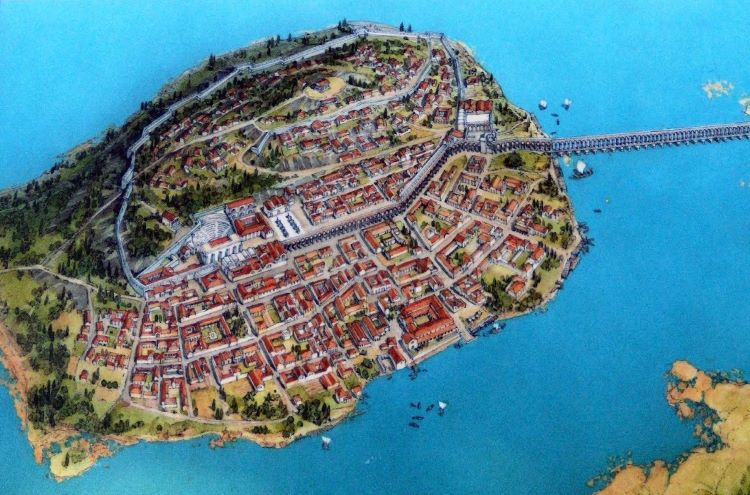

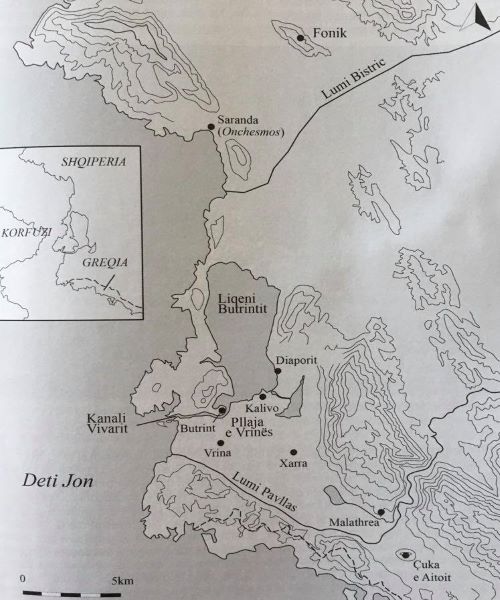

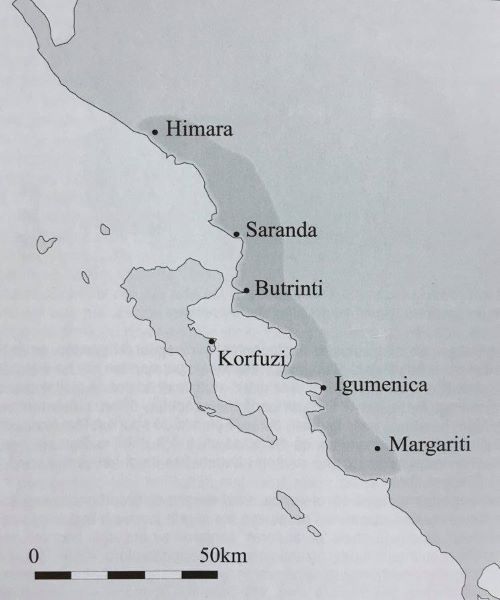

The ancient city of Buthrotum (modern Butrint) stood three km from the Corfu Strait, on the southern edge of Butrint Lake/Lagoon. A narrow channel, the Vivari Channel, connected Buthrotum and its port (ancient Pelodes Limen in the Butrint Lake) with the open sea. The citadel itself stood in a small peninsula washed on all sides by the safe waters of the Butrint Lake and connected with the mainland only through a narrow isthmus. By occupying such a naturally defended and strategic position, Buthrotum flourished at different eras as a stunning urban establishment.

The city of Buthrotum was inhabited by the Illyrian tribe of the Presaibes who later formed a distinct league. The Presaibes were either a subtribe of the Chaeones or a tribe in its own right.

Legends of Origin

Buthrotum formed as a city sometime in the V century B.C.E. Many ancient authors suggest a legendary descent for its founders; namely, the city was built in the image of Troy by Trojan exiles led by Helenus, son of Priam. This same Helenus married Hector’s widow Andromache whom Pyrrhus Neoptolemus (son of Achilles) had brought into Epirus as his slave. With her, he ruled the city and the region that was named Chaonia after the Trojan hero Chaon. A Pergamus, modeled after the Trojan citadel, was erected in the acropolis (a son of Andromache with Pyrrhus named also Pergamus later founded the famous Pergamon in Asia Minor), completed, like in Troy, with a Scaean Gate. A dry creek was named Xanthus, after the river of Troy.

The early city was developed around a water source famous for its healing powers; along it developed the sanctuary of Asclepius where pilgrims would seek healing and devote offerings to a nearby small temple. By the III century, the city expanded to form a theatre and a peristyle building (likely a hostel for pilgrims). The complex was enclosed by a “temenos” wall that defined the precinct of the sanctuary.

A Richer Community

The city of Buthrotum flourished for the first time in the II century B.C.E., after an important period of prosperity under Pyrrhus of Epirus. The transnational seaborne trade brought substantial benefits to the inhabitants of Epirus, though most profits went in favour of Ambracia. In 170, the commercial dynamics changed in favour of Buthrotum, following the Third Macedonian War and the devastation of the Molossian lands by the Romans. In an area with less commercial competition, commercial ships flocked the harbours of Buthrotum and Corcyra.

The prosperity of the II century is testified by the many acts of manumissions (liberation of slaves) dated after 163. These acts, most of which date in between the years 160-100, illustrate a substantial increase of slave-owners and a richer community. This prosperity contributed to the reconfiguration of the sanctuary and the construction of the agora.

The First Wave of Roman Settlers

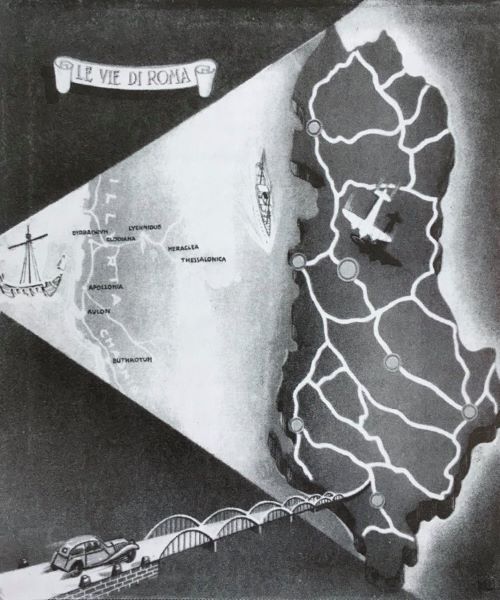

In early 48 B.C.E., Julius Caesar briefly harbored at Buthrotum, a visit that would have a key impact on the city. When the dictator returned to Rome, he issued a decree that projected Buthrotum as a Roman colony. Despite the efforts of Cicero and Pomponius Atticus to curb the project, in 44, a group of settlers arrived into the city led by Lucius Munatius Plancus. However, rather than a large group of veterans, the new settlers were likely limited in number and mostly made up of civilians. As such, the colons did not cause a radical change in the demographic composition of the city or its urban nature. There was, however, an immediate political change.

A new constitution was established over the city, modeled on that in Rome. It created a local senate (or council of decurions), two annual magistrates (the duoviri), and, among others, the office of the quinqueenal, suggesting that a citizen roll was being preserved. Latin was declared the official language and the city was granted the right to issue its first coins. The coins issued by the earliest recorded duoviri at the city, P. Dastidius and L. Cornelius, illustrate the radical change of the Buthrotian elites as well. The earliest coins named the colony as C. I. BUT i.e. Colonia Iulia Buthrotum.

The Patronage of Pomponius Atticus and Agrippa

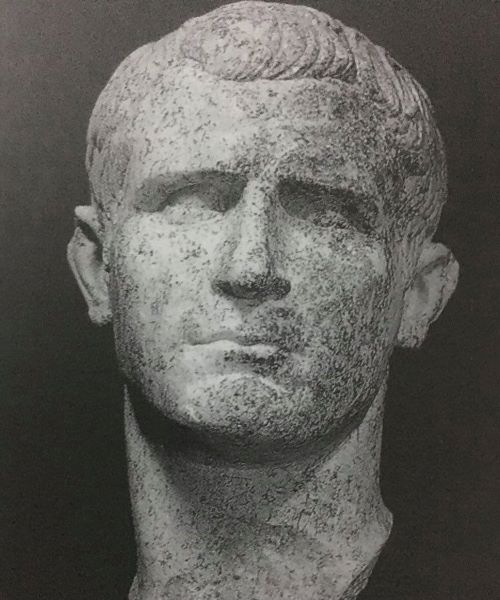

The Pomponius family held an esteemed position in the newly refounded colony. Titus Pomponius Atticus owned important, large properties around Buthrotum since 64 B.C.E. Pomponius Atticus moved into his rural villa in the nearby Buthrotum, Amaltheum, in 59 B.C.E. His correspondence with Cicero in favor of the city not becoming a colony of veterans is well documented. The daughter of Pomponius Atticus, Caecilia Attica, married Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa four years before the battle at Actium (35 B.C.E.). This same Agrippa married later, in 29 B.C.E., the niece of the emperor himself, Claudia Marcella Major. As such, the Buthrotians found in Agrippa a new protector in the figure of whom fused both the inheritance of Pomponius Atticus and the ties with the imperial court.

After 32 B.C.E., the city found its new protector in Agrippa and expressed its gratitude through marble statues depicting him and Caecilia. In 29 Agrippa married Claudia Marcella Major, niece of Octavian Augustus, a match that made Agrippa an even more important figure for the interests of Buthrotum. In 23, Agrippa married yet another Augustan royal, Julia the Elder, daughter of the ruling emperor. Himself, Agrippa welcomed the privileges attributed to him by the Buthrotians; in the period 16-13 B.C.E., he sojourned along with his wife Julia east, and a visit to Buthrotum is not unlikely. It’s likely that one or both of the dumviri who issued coins of Buthrotum during this time, M. Pullienus and L. Ateius Fuscus, were also subordinates of Agrippa.

An Augustan Investment

The reign of Octavian Augustus heralded a new age of prosperity for Buthrotum. The city was refounded as the colony C. A. BUT or Colonia Augusta Buthrotum. Upon the turn of the millennium, an active cultural exchange between Buthrotum and Rome took place. The ties were mutually beneficial. The new imperial authority viewed Buthrotum as the new designated center; the main image of a new regional reality. Buthrotum was to replace Dodona, the centuries-old center of the old Epirote Alliance and then the League of Epirus, in regional importance.

Apart from using ties with high ranked officials to gain favors, the Buthrotians also used their legendary descent for the same purpose. The citizens of Buthrotum could claim to be the successors of those who welcomed Aeneid into Epirus; the same Aeneid that would later found the city of Rome. Both Rome and Buthrotum had, thus, a common legacy that united them culturally and politically.

The Aeneid

The promotion of common cultural ties culminated in 19 B.C.E., when Virgil, under Octavian’s patronage, published his “Aeneid”, a poem on Aeneas wondering before he founded Rome. In the story, Aeneas makes a memorable stop at Buthrotum, a city he found to be modeled after Troy. Before departing again, the hero delivers this message to Helenus (the Trojan founder of Buthrotum):

“Live and be appe, as should those whole destiny is now achieved; we are still summoned from fate to fate. Your rest is won. No seas have you to plough, not have you to seek Ausonian fields that move forever backward. You see a copy of Xanthus [the name of the creek] and a Troy, which your own hands have built, under happier omens, I pray, and better shielded from Greeks. If ever I enter the Tiber and Tiber’s neighbouring fields and look on the city walls granted to my rave, hereafter of our sister cities and allied peoples, Hesperia allied to Epirus – who have the same disastrous story – of these two we shall make one Troy in spirit. May that duty await our children’s children!” (Aeneid. 3.493–505. From “The Trojan Connection: Butrint and Rome” by Inge Lyse Hansen.

Virgil’s paragraph was a contemporary, mutually beneficial propaganda that presented both Buthrotum and Rome as sharing the same descent and friendship. The lines must have resonated particularly with the Buthrotians who used their heralded Trojan descent to benefit political and financial favors.

Post-Augustan Buthrotum

After the reign of Octavian, there are strangely few sources that suggest a connection between the imperial house and Buthrotum; and that is despite the daughter of Agrippa and Caecilia Attica marrying the future emperor Tiberius sometime in 16-12 B.C.E. Even though the city continued its coin production, there has been no coin discovered bearing the names of either the second Roman emperor Tiberius or its successor Caligula. Yet, a preserved inscription suggests that the city continued its efforts to maintain a connection with the imperial family.

According to the epigraphic evidence, in 12 C.E., Germanicus, designated as the heir of Tiberius, was honored as a quinqueenal in Buthrotum. The honor is a further testimony of the special status that Agrippa and his family enjoyed in Buthrotum (Germanicus had married in 5 B.C.E., Agrippina the Elder, daughter of Agrippa and Julia the Elder) as much as of the deliberate efforts the Buthrotians made to ensure patronage from the imperial circles.

Clientele During the Reign of Claudius and Nero; Connections with the Domitii Ahenobarbi

At the beginning of Claudius’ reign, the coins of Buthrotum bore the initials CCIB that meant Colonia Campestris Iulia Buthrotum. This new official name that persisted during the reign of Nero as well, celebrated the large-scale investments carried in the city. Notably, it was during this time when a whole new neighborhood developed eastward in the land opposite, in “Fushe-Vrinë” or Vrina Plain. In Nero’s time, the aqueduct/bridge stretching from the Vrina Plain into Buthrotum was completed, an investment likely initiated some decades ago by Octavian Augustus.

Buthrotum’s connection with the notable Ahenobarbus’ family (the Domitii Ahenobarbi) proved valuable during the reign of Claudius and Nero. The citizens of Buthrotum had honored in 16 B.C.E., Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus as a protector of their city. He was the grandfather of Valeria Messalina whom emperor Claudius took as his third wife; upon Claudius’ accession, Messalina brought to him a son, Britannicus. Messalina was also the paternal cousin of Claudius’ successor Nero. It’s clear that the city tried to use its connection with Messalina to maintain a precious connection with the ruling emperor.

The imperial attention to the region culminated 66/67 C.E. when Nero took his famous tour east. In Epirus, Nero is reported to have visited Corcyra, Cassiopea, and Nicopolis, even presiding twice over the Actian Games. There is no evidence of Nero visiting Buthrotum but the imperial visit was enough to encourage Roman political influences in the region. This was the case for Buthrotum as well as for the neighboring city of Phoenice.

Urban Expansion

After the reign of Nero, the connections with members of the Domitii Ahenobarbi became inappropriate. At this time, Phoenice competed effectively in commerce with Buthrotum, increasing its economic influence over the whole region. It was at this same time when Buthrotum stopped issuing its own coins whereas Phoenice continued its coin production, until the reign of Trajan. After Trajan’s rule, Buthrotum regained its superior economic position in the region through real estate developments and new ties with the Roman aristocracy.

The first half of the II century was a period of urban expansion for Buthrotum. The buildings around the Sanctuary of Asclepius and the Forum were reconfigured and given a monumental nature. Numerous urban villas spread across the city, including the peripheral part at the Vrina Plain. The wide bridge and aqueduct that connected the city with the periphery also served to link them with the main road that went from Aulona to Nicopolis. As in previous decades, the city made excellent use of every connection to ensure the support of Roman aristocracy. This was the case when, in the late II or early III century, the city council awarded the then pro-consul of Macedonia Marcus Ulpius Annius Quintianus with the title of the patron. Dedication to statues as well continued to be a method the city used to gain political favors.

Destructive Quakes

During the mid-II century, the Capitolium in the Forum collapsed; its materials were used as spolia. The sanctuary was also destroyed around this time. The Forum remained in use for another century, losing its function when its surrounding public buildings collapsed. Even though most public areas lost their function, a good number of rich inhabitants continued significant investments in private estates. The best example of the spread of grandiose private residence is the so-called Triconch Palace. The property was likely the property of an individual of senatorial rank. During the third century, the Triconch became more and more enlarged and magnificent.

During the fourth century, the area was affected by natural disasters mainly caused by seismic activities. A cataclysmic earthquake hit Buthrotum in 35 causing severe damage to buildings across the city. The earthquake, with its epicenter likely in Buthrotum, damaged seriously, among other structures, the Roman Forum and the Triconch Palace. The tremors caused an evident slope in the southern side of the Forum. Meanwhile, the inhabitants of the Triconch Palace had to temporarily abandon their residence until they reconstructed it and its damaged domus in 400.

The earthquake of the mid-IV century was likely not the only quake to damage Buthrotum in the fourth century. Notably, another cataclysm dated in 365 devastated the coastal areas of the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea, including Buthrotum. According to Theophanes the Confessor and George Hamartolos (“George the Monk”), a disastrous tsunami affected the eastern Adriatic and Ionian coast, a natural disaster that shakened Buthrotum on a large scale.

New Fortification

From the second half of the fifth century, investments were mainly made for church constructions. Simultaneously, the residential estates begin to lose their splendor and size. Over the ruins of a Roman villa in the nearby Diaporit, a new Christian complex is built during 490-500. By the second quarter of the VI century, anonymous donors erected the Basilica at the Vrina Plain. The construction of another religious building, the Baptistery, marked the end of the Roman Buthrotum.

While these Christian structures were established, the Triconch Palace had turned into a small, modest house for the processing of seashells. The citizens kept however profiting economically from the strategic position of Buthrotum near the Corfu Strait. As for literal evidence, the city is mentioned in the correspondence of bishop Stephan dated 458.

During the late fifth century – early sixth century, the emperor Anastasius (r. 491-515) built the new fortifications of Butrint. This initiative was part of the emperors’ infrastructure programs in the region, peaking with the construction of the astonishing walls of Dyrrachium. The new walls surrounded a surface larger than that of the Hellenistic era. In the south and east, the walls run along as far as the shores. The northern part relied on the well preserved Hellenistic walls and gates. The most extensive defensive works took place in the western part, most vulnerable to land assaults. Thus, a series of rectangular towers reinforced this section of the wall.

A VI-Century Drama

During the VI century, the urban topography of Buthrotum continued to change; a series of Christian buildings were built while the dwelling of residents dropped dramatically across the lower city and south of the Vivari channel. After this century onwards, the water levels in the area decreased significantly, enough to change and affect the overall settlement. This retraction of the sea made the inner harbors and docking bays obsolete as in the case of Ephesus and Troy in Anatolia. From a well-enclosed port-city, Buthrotum turned into a modest inland dwelling surrounded by marshes and cane swamps.

It’s unclear how much the topographic changes of the seacoast affected the city during late Antiquity; it may well be that the changes in water levels were insignificant for the populace. This continuation of urban life is documented by literal sources as well. In 516, the episcopal correspondence of bishop Mateos. It also appeared in the “Synecdemus” of the Byzantine geographer Hierocles, written during 527-528. The Synecdemus, an authoritative source in the time of Justinian I (r. 527-565), lists Buthrotum as the seventh city of the Epirus Vetus province whose center was at Nicopolis.

The VI century was a gloomy time for the Buthrotians, literally. Sometime in the timeframe 526-593, the volcanic crater of Forgia Vecchia on the Pilato Mountain in Lipari reactivated after three thousand five hundred years. Though far away into the Tyrrhenian Sea, it’s volcanic ashes spread for a distance of 600 kilometers. The western winds immersed Buthrotum in the spread in what must have been a bad omen for the locals.

Destabilization

Radical changes affected Butrint in about 550, a change reflected in the constructive nature of the city. During this time, the monasterial complex and the church in the nearby Diaporit, unprotected by walled fortifications, were abandoned. Supplies of luxury items and amphoras from Tunisia and North Africa fall significantly. This shows that, despite Justinian’s reconquest of Africa, Buthrotum did not profit from the emperor’s venture. On the contrary, the efforts of Justinian to reunite the Empire had a destabilizing effect over the city in the form of more taxation and less commerce.

During this same time, Barbarian invasions contributed to the unstable political situation of the region. In 547/548, the Slavs looted the nearby Onchesmus. In 551, the city endured an assault from the Osthrogotics pirates of Totila. The raids of the Avars had also spread across the Balkans.

From all the incursions those of the Slavs were the most persistent. In 586/587, the Slavic tribe of the Baiunetes took a serious assault on the region, burning Onchesmus and forcing the flight of the locals south and west, into the Ionian Islands and southern Italy. The correspondence of the pope Gregory the Great (Papacy: 590-604) testified to this migration becoming a transnational problem. The Chronicle of Monemvasia and the work of Arethas of Caesarea suggest that those who fled did not return. Some suggest that the mark of the Slavic invasion remained present in the form of the medieval toponymy “Vageneria” standing for the Baiunetes; later, it allegedly transformed into “Delvina”; (the Partitio Romaniae, document of 1204, compilled based on the Byzantine tax registers, mentions, among others, the Chartularaton de Bagenetia).

An Ancient Pandemic

And then there was the so-called Justinianic Plague (541-549), one of the worst pandemic that hit the Byzantine Empire including Buthrotum. The disease would remain a problem in the Mediterranean area for another 225 years since its first outbreak.

The combination of the various destabilizing factors caused, if not an economic collapse, an economic recession in Buthrotum. The process of decline accelerated in the early decades of the VII century where there are no reports of new constructions or even coin usage. The material culture pertaining to this period is scarce; in 650 it vanished completely suggesting an almost complete dereliction of the area.

The Castrum

By the seventh century, the small community at Buthrotum had no longer access to imports. Meanwhile, the local economy was based on non-monetary transactions with coins disappearing from use. One of the main features of this period is that of the materialistic simplicity, continuing through the VIII century.

The manner in which the Balkan society organized itself in the centuries following the rule of Heracles (610-641) is unclear. It seems that the community was governed by local, powerful leaders of groups of prominent families and their armed escorts. These governors, who acted on an expanded autonomy, accepted the feudal authority of the Byzantine Empire in return for receiving imperial titles. This rural, provincial aristocracy maintained closed political as well as commercial ties with the court at Byzantium.

In 700, Buthrotum had decreased into a peripheral Byzantine fortress without meaningful ties to a central administration. The continuation of life during this time remains a debate among scholars. The theory that reconciles all accounts states that Buthrotum served mainly as a seasonal habitation for a few locals that fished in the lake. The location also appeared in the Notitia Episcopatuum compilled sometime after 754. The document lists Buthrotum as Bythipotu and as the fourth city of Epirus Vetus. This reference likely referred to a small castrum that developed in the Western Fortification. The natives had turned the towers into housing buildings as these structures served no longer a defensive purpose. This place was based on the local administration that governed all the area.

An Enigmatic Destructive Fire

In 800, a cataclysmic fire destroyed the castrum of the VIII century. The assault was apparently launched against a Byzantine garrison stationed here. Rather than a large-scale assault, the fire likely targeted the local elites exclusively. As such, the disaster resembles internal civil strife, not uncommon in the Ionian region. In about the same year, a Byzantine representative was sent into the province of Cephalonia (the included the Ionian Islands and Corfu) to hear the many complaints of the local population. On the other hand, a Slavic incursion cannot be overlooked (in 805, the Slavs sacked Patra).

After the fiery destruction of the early Medieval castle, the community of Buthrotum relocated in the periphery at the Vrina Plain. For some generations during 840-950, a “new Buthrotum” was reestablished here. This “new” community maintained its communication with the original city at the peninsula by using boats or the Roman bridge across the Vivari Channel. Though it had abandoned the original establishment, the inhabitants still exercised authority over the peninsula from their new location in the opposite plain.

Archon & Apostasy

It was at the Vrina Plain where most of the local economic and political activity of the IX-X century took place. There is a return into the use of coins as well as of limited imports from southern Italy. Sometime during the mid-IX century over the ruins of the fifth-century basilica, a new house was built. The function of this building was administrative, likely the residence (Oikos) of the local governor/commander (archon). The Byzantine officials had reinforced the narthex of the old basilica and turned its upper floor into a small living quarter.

The discovery of five bronze seals in the area sheds further light into the location revealing the important administrative role of Buthrotum. A Byzantine silver coin (miliaresion) of the emperor Leon VI (866-950) is an important evidence on the revival of the monetary-based economy.

The house of the archon continued to serve its purpose until the mid X century when it was abandoned. During the same time, the Vrina Plain was also abandoned, again.

The apostasy of the mid-X century was short; late in this same century, Buthrotum was repopulated again. During this time, the city became popular as an important supplier of mussels and fish; a fact supported both by archaeology and literal source. The locals had turned the towers of the western fortifications into places of mussels processing. Arsen of Corfu, who visited Epirus to negotiate with the Slavic pirates to stop their raids, mentioned Buthrotum as rich in fish and oysters.

Revival

Christianity remained an important aspect during the X-XII century when the bishop of Buthrotum served as the assistant bishop of the central diocese of Naupactus. In the late IX century, Saint Elias the Younger along with his companion Daniel were accused as Arab spies (Hagarenes) and imprisoned in Buthrotum (polis epineios) during 881-882. In 904, the relics of Saint Elias the Younger were brought to Buthrotum via Thesprotis; then they were later sent by ship in Calabria (southern Italy). As for Buthrotum, it remained a part of the ecclesial province of Nicopolis.

The revival of the mid-X century continued at such a fast pace that the citizens began reclaiming the lands that previous generations had abandoned in the peninsula. They applied this reclamation through terraces near the acropolis and division of the properties with partition walls. The inhabitants also reuse the premises of the old Triconch Palace for erecting new stone structures. By the late XI, the local community had entered the network of international trade, dominated by imports of ceramics from the eastern Mediterranean.

Buthrotum’s Fall under Foreign Rule

In 1205, Buthrotum was included within the boundaries of the Despotate of Epirus under the rule of Michael I Angelus Comnenus. In 1258, after a marital arrangement, the city was awarded to Manfred Hohenstaufen, king of Sicily. The latter gave it to the king of Naples Charles I of Anjou in 1279. For more than a century the Buthrotum remained under Angevin’s possession enduring difficult times under them. The inhabitants built new fortifications and restored the old ones in order to endure the even increased dangers of the period.

The last decades of the XIV century mark the beginning of the ultimate fall of Buthrotum. In 1386, after the rule of Charles III of Anjou, the Venetians bought the place which they kept until the late XVIII century. Not long after the purchase, in 1394, the castrum Butentroi appeared as in much need of repairs. The Venetians built a castle near the old acropolis of the site where the new administrative center was gradually shifted. This castle was abandoned in the late XVI century.

“In an attempt to reduce the financial burden of maintaining Butrint, a new fortress was built on the south side of the channel by the Venetians in the XV century. This fortress, known as the Triangular Castle defended the fish traps of Butrint which were the primary financial assets of the settlement in this period. Soon after the fortress was built, the old town was abandoned in its favor“. (Inge Lyse Hansen & Richard Hodges; Roman Butrint – An Assessment).

Bibliography

Bescovy, D.; Barclay, J; & Andrews J. (2008). Shenjëtorë dhe mëkatarë: Një tefro-kronologji për ndryshimin e peizazhit të antikitetit të vonë në Epir nga historia shpërthyese e Liparit, ishujt aeolian.

Bowden, W. & Hodges, R. (2005). “Një periudhë akullnajore mbi Perandorinë Romake”: Butrinti post-romak mes strategjisë dhe rastësisë së fatit.

Hansen, I. L. (2007). Lidhja Trojane: Butrinti dhe Roma. (Original: The Trojan Connection: Butrint and Rome).

Hansen, I. L. Një statujë togati e kohës së Antoninit nga forumi i Butrintit.

Hansen, I. L. & Hodges, R. (2007). Roman Butrint; An Assessment.

Hernandez, D. R. & Condi, Dh. (2008). Forumi romak në Butrint (Epirus) dhe zhvillimi i tij nga periudha helenistike në atë mesjetare.

Hernandez, D. R. Buthrotum/Bouthrotos (Butrint, Albania).

Hodges, R. A New Topographic History of Butrint, Ancient Buthrotum.

Kamani, S. Fortifikimi Perëndimor.

Kamani, S. Butrinti në Shekuj.