First Illyrian War: Roman Republic’s First Military Engagement in Eastern Adriatic

The First Illyrian War was fought between the Romans and the Illyrians during 229-228 B.C.E. Rather than the actual combats, scholars have tended to matters related to reasons that pushed the Romans into this war and the nature of Roman possessions after the war. The First Illyrian War represents Rome’s first military campaign east of the Adriatic and Ionian Sea. Thus, the dynamics of this war are important for understanding the nature of early Roman expansion in the east.

Rome before the First Illyrian War

In 241, Rome had come up victorious in the First Punic War. That conflict had brought the Republic a considerable navy and possession over Sicily. The fleet would prove valuable in the upcoming conquest of Sardinia and Corsica that began in 238. At about the same time the Republic fought the pirates of Liguria showing specific concern for naval affairs.

During the conflict with Carthage the Romans had realized that the long coast of Italy was vulnerable to seaborne assaults. During that time, Hamilcar Barca had raided Locri and other areas across southern Italy. Thus, the Republic, in 244, established a colony at Brundisium (current Brindisi), conveniently facing the Ionian Strait. However, commercial factors also influenced the decision to establish a Latin colony at Brundisium. As Zonara writes, the Romans were aware that Brundisium “had a fine fine harbour, and for the traffic with Illyricum and Greece there was an approach and landing-place of such as character that vessels would sometimes come to land and put out to sea wafted by the same wind”. (Zonara VIII.VII).

The colony of Brundisium was of such economic importance that, by mid III century, Rome had extended the via Appia. The road, originally linking Rome with Capua, expanded all the way into Brundisium, via Beneventum, Venusia, and Tarentum. Now, the cross-Adriatic and cross-Ionian commerce brought goods coming into Brundisium directly into the city of Rome. Trade with the eastern Adriatic intensified along with interests on eastern affairs. In about 240, the city of Apollonia in the Ionian Sea sent an embassy in Rome. This marks the first formal communication between the Roman Republic and an eastern Hellenic polity.

The Gallic Frontier

In the early 230s, Rome had pressing issues at home. After almost half a century of peace, the Gallic tribes of the Po valley gathered a large force and threatened the northernmost part of the ager Romanus. Yet, internal disagreements dissolved the forces of various Gallic tribes by two hundred thirty six, saving Rome from trouble.

Continuous Roman advance north threatened the Gauls who, in two hundred thirty one, once again mustered a large force. These tribes, led by the people of Insubres and Boii, kept Rome under threat for several years. In fact, tensions between Rome and the Gauls continued even during Rome’s intervention in Illyria. This makes the Roman decision to wage war on another front, while still facing problems at home, even stranger. However, it also explains why the Romans aimed to conclude the war with the Illyrians as soon as possible. It was only in 225, after the First Illyrian war, that Rome won a decisive battle against the Gauls near its territory.

The Illyrian Ardiaei before the Roman intervention

Prior to Roman intervention in Illyria, the Illyrian tribe of the Ardiaei had created a powerful monarchy. It extended from the Narona (Neretva) River into the Drin River. Under the rule of king Agron (r. 250-231), the Ardiaeans relied heavily on naval warfare to expand their interests. This domination culminated with a seaborne assault on the Acarnanian Medion where the Ardiaeans defeated the Aetolians. The Ardiaean state could count on a total force of a hundred ships and thousands of organized infantry.

By 231, Illyrian aggression had already disrupted the cross-Adriatic trade. At about this time, king Agron succumbed to pleurisy caused by excessive festive drinking. He let his infant son Pinnes as heir, but Teuta, one of Agron’s widows continued to govern the affairs as a regent ruler. Teuta continued Agron’s policy of naval domination with even more determination. Moreover, she also hoped to gain possession of all the colonies located along the Illyrian coasts. These targets were notably Issa, Dyrrachium, Apollonia, and Corcyra.

During the campaigning season of 230, a land force under Teuta’s general Scerdilaidas overran Epirus. Meanwhile, an Illyrian naval force had already anchored off Onchesmus. Here, disembarked troops conquered the nearby Phoenice, capital of the new but vulnerable Republic of Epirus. The Ardiaean incursion forced the Epirotes into settling for an alliance with the Ardiaean state. Acarnania, the adjacent state, followed suit. In rapid succession, the Ardiaean monarchy could count on the alliance of Macedon, Epirus, and Acarnania.

The Nature of Literal Sources

There are two main literary traditions explaining the motives behind Roman decision to wage war against the Illyrians. The first follows the Polybius while the second follows a combination of Cassius Dio/Zonaras and especially Appian. According to Polybius, the Romans decided to fight the Illyrians because the latter had disrupted the cross-Adriatic trade. For Polybius, or the sources he trusted, the Illyrians were mere pirates with no sense for order and law. On the other hand, Appian describes the Roman intervention as responding to an appeal for help from the Issaean League. Both accounts seem to contain elements of the truth, though they are not ideal.

Polybius’ account is openly pro-Roman. His claim on Illyrian naval activity as piracy is highly subjective. It follows a strict Roman viewpoint. As far as Illyrians were concerned, their “piratical” assaults had either the nature of naval manoeuvres conducted on their sovereign waters or proper military campaigns. Thus, the naval incursions were hostile, but they were not hostile to the Romans. Furthermore, these incursions were organized, with clear expansionist intentions, thus, not piratical. Polybius’ account is also tainted with a stereotypical Greek view of the “barbarian” other and female gender.

Appian’s narrative, on the other hand, is more neutral. Issa had close commercial and cultural ties with southern Italic areas. Archaeology supports this claim through the discovery of many amphorae of Apulian origin or crafted using Apulian models of the III century. This relation explains why Issa would ask Rome for help when the Illyrian threatened its possessions and disrupted its trade. However, Appian’s account is more compressed and far shorter than that of Polybius. Thus, it reveals less details on the war and faces chronological issues.

Audience with the Queen

After the capture of Phoenice, complaints before the Roman Senate intensified. Polybius also mentions an Illyrian assault on Italic merchant ships somewhere off Onchesmus. Thus, the Republic sent Gaius and Lucius Coruncanius in Illyria to investigate the accusations. The envoyes arrived somewhere near Issa, at a time where that island was besieged by the Ardiaei. The Roman ambassadors had an audience with Teuta but the record of that conversation in Polybius is likely a fabrication. It goes as follows:

“…they [the Roman envoys] began to speak of the outrages committed against them. Teuta, during the whole interview, listened to them in a most arrogant and overbearing manner, and when they had finished speaking, she said she would see to it that Rome suffered no public wrong from Illyria, but that, as for private wrongs, it was contrary to the custom of the Illyrian kings to hinder their subjects from winning booty from the sea. The younger of the ambassadors was very indignant at these words of hers, and spoke out with a frankness most proper indeed, but highly inopportune: “O Teuta,” he said, the Romans have an admirable custom, which is to punish publicly the doers of private wrongs and publicly come to the help of the wronged. Be sure that we will try, God willing, by might and main and right soon, to force thee to mend the custom toward the Illyrians of their kings.” Giving way to her temper like a woman and heedless of the consequences, she took this frankness ill, and was so enraged at the speech that, defying the law of nations, when the ambassadors were leaving in their ship, she sent emissaries to assassinate the one [apparently Lucius Coruncanius] who had been so bold of speech”. (Pol. II. VIII. VI-XII).

Rome Prepares for War

In truth, most scholars agree that in no circumstance did Teuta order the assassination of a Roman envoy. Teuta’s position in Appian is less tainted. The latter, in addition to an Illyrian assault “on the Roman Coruncanius”, mentions the assassination of a certain Cleemporus on that same assault. This Cleemporus was an envoy of Issa, at that time blockaded by sea. If the Illyrian assault was a reaction to an Issaean escaping the blockade then this makes the incident an action of warfare. In that situation, the “Roman Coruncanius” happened to be on the same boat with Cleemporus. He was not the direct target of the assault.

Yet, the idea of a “barbarian” queen ordering the assassination of a Roman ambassador played with the emotions of the Roman people. It provided a convenient “casus belli” that gained the support of the Senate and the Roman citizens’ assembly. The Republic began preparations for the war.

The Roman strategy would follow a similar pattern as what the Republic had already followed west, in Sardinia and Corsica. When they conquered these islands during 238-227 they first targeted the most strategic naval bases. Then, they gradually pressed from there inland facing manageable resistance along the way.

The Illyrian Campaign Against Corcyra

By 229, Teuta sent two separate naval forces to conquer Epidamnus and Corcyra respectively. Her conduct suggests she was not aware of Roman levying a force against her. She continued her policy of coastal and naval hegemony without taking into account a potential Roman intervention.

According to Polybius, the Illyrians made an attempt to capture Epidamnus (i.e. Dyrrachium) by a stratagem. These Illyrians “were received by the Epidamnians without any suspicion or concern, and landing as if for the purpose of watering, lightly clad but with swords concealed in the water-jars, they cut down the guards of the gate and at once possessed themselves of the gate-tower. A force from the [Illyrian ships was quickly on the spot, as had been arranged, and thus reinforced, they easily occupied the greeted part of the walls. The citizens were taken by surprise and quite unprepared, but they rushed to arms and fought with great gallantry, the result being that the Illyrians, after considerable resistance, were driven out of the town” (Pol. II. IX. III-V). The Illyrian force that the Epidamnians drove out sailed south and joined the other part of the fleet at Corcyra. The united fleet disembarked troops on the island that besieged its citadel while ships blocked the harbours.

Citizens of Corcyra, along with envoyes from nearby Apollonia and Dyrrachium, sent an appeal to the Achaeans and Aetolians. Soon, the two leagues prepared a relief force of ten decked Achaean ships crewed with soldiers from both leagues. The Achaean-Aetolian set sail north, for Corcyra, but the Illyrians, aware of the advance, intercepted them off Paxos. Apart from their own ships (which could range to about twelve vessels), the Illyrian could count on seven decked Acarnanian ships.

Naval Battle off Paxos

Off Paxos island, a naval battle took place:

“The Acarnanians and those Achaean ships which were told off to engage them [the Acarnanians] fought with no advantage on either side, remaining in their encounter except for the wounds inflicted on some of the crew. The Illyrians lashed their boats together in batches of four and thus engaged the enemy. They sacrificed their own boats, presenting them broadside to their adversaries in a position favouring their charge, but when the enemy’s ships had charged and struck them and getting fixed in them, found themselves in difficulties, as in each case the four boats lashed together were hanging on to their beaks, the [Illyrian] marines leapt onto the decks of the Achaean ships and overmaster them by their numbers. In this way they captured four quadriremes and sank with all hands a quinquereme” (Pol. II. X. II-V). The other remaining Achaean ships had no choice but to retreat and return into their homeland.

The victory over the Achaean-Aetolian naval force left the besieged Corcyra without any foreign aid. Thus, the colony surrendered to the Illyrians and accepted their terms. The conquerors placed an Illyrian garrison in the town under the command of Demetrius of Pharos.

Roman Arms and Amicita

The Illyrian victory off Paxos and conquest of Corcyra showed that Greek states were unable to check Illyrian expansion. It’s at this time when Roman forces appear on the Illyrian coast. Gnaeus Fulvius, Roman consul for the year, sailed with two hundred ships towards Corcyra, initiating the First Illyrian War. The Romans had already corresponded in secret with Demetrius of Pharos, commander of the Corcyraean garrison. The latter had promised them that he would turn into the Republic’s side and surrender the island to them. Thus, when Roman navy appeared off Corcyra, Demetrius switched sides and surrendered the citadel to the Romans. The Romans placed the other Illyrians of the garrison under custody. Soon, the Roman fleet approached Apollonia, taking them on their side as well.

After getting hold of Corcyra, the Romans were reinforced with the main army led by Aulus Postumius, the other consul. This force that sailed from Brundisium consisted of 20,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Through combined naval and land assaults, the united Roman army conquered Apollonia and then, Epidamnus/Dyrrachium. The pro-Roman approach of some of the local aristocracy helped the Roman advance in here. The ruling class of these colonies welcomed the Roman authority in exchange for maintaining the property rights and commercial freedom.

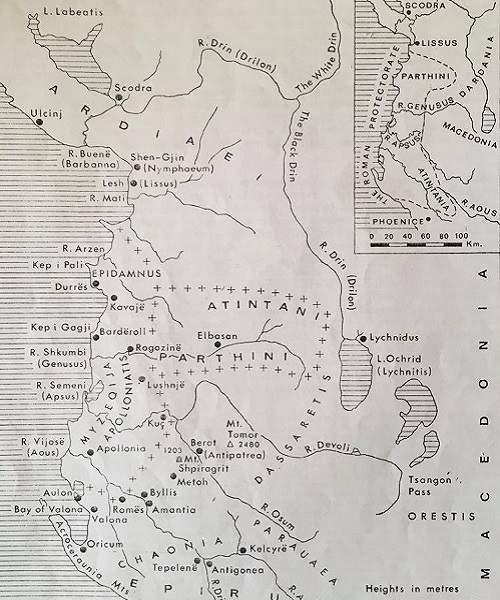

With these major cities now under control, the Romans met with other, inland communities. From the tribes that appeared in the Roman headquarters, the Republic included the Parthini and the Atintani into their friendship (“amititia”). For Rome, ties with these tribes meant they could better control the cities they had just gained. For the Parthini and the Atintati, it meant they could continue, unhindered, their essential trade with the coastal colonies.

Conclusion of Combats

Soon, the Romans had control of the sea belt that ran from Corcyra to Lissus. Their divided enemies were unable to organize any meaningful resistance here. The surrender of Corcyra is solid proof of their inner conflicts. The Romans encountered real, organized military resistance only when they advanced north of Lissus. A major battle took place at Nutria, an unknown location, where Romans lost “not only many soldiers, but some of their military tribunes and their quaestor”. (Pol. II. XI. XIII). However, despite the losses, the legions managed to conquer that location. Another direct clash took place at the Atyri hill, another unidentified place. The Romans come up victorious again. They captured other small towns near the coastline but it became clear that, on land, they had moved into uncharted territory.

By the time the Roman fleet reached Issa it was clear that the Illyrians had lost their cause. Those Illyrian ships besieging Issa, at the sight of the large Roman navy, gave up their investment. Already compromised by Demetrius of Pharos’ men among their ranks, the Ardiaean “loyalist” mariners took shelter at Arbon, in the continent opposite Issa. Meanwhile, the Romans guaranteed safety to those supporting Demetrius of Pharos who regrouped in Pharos island.

The liberation of Issa concludes the military maneuvers and fighting of the First Illyrian War. Teuta, with a trusted group of followers, positioned in Rhizon, relying on the capital’s strong natural defense. Here, any naval incursion from an enemy fleet had to cross the dangerous fjords of the sinus Rhizonicus (gulf of Rhizon; current gulf of Kotor) where locals could easily ambush the foes. On the other hand, protected by highlands, a land approach to Rhizon was equally risky.

Treaty with the Ardiaei

During the winter of 229/228, Teuta likely hoped for a full retreat of the Roman forces from Illyria. Yet, while most of the Romans and Gnaeus Fulvius went to winter at Brundisium, Aulus Postumius did not leave. He wintered in Dyrrachium with forty ships and a conscripted force “from the surrounding states” (Pol. II. XII. II). This force was enough to keep guard of the new Roman possessions and impose a winners’ treaty over the queen. Eventually, Teuta concluded the treaty with the Romans in the spring of 228. According to this agreement Teuta committed to paying a war indemnity, evacuate her troops from the Illyrian coast, and not sail south of Lissus with more than two lembi, even those unarmed. Soon after the treaty (or even before it), Teuta either abdicated from the Ardiaean throne or other forced her into abdication.

Although victorious, the Romans had no long-term plans on governing their new gains directly. As such, they did not exterminate the Ardiaean monarchy. The Republic revognized the legitimacy of Agron’s infant son Pinnes as an Ardiaean successor as long as the latter committed to the terms of the treaty. However, the Romans promoted Demetrius of Pharos into the Ardiaean regency to act as an effective ruler on behalf of Pinnes. The Romans thought of Demetrius as a convenient client king; ideal for advancing Roman agenda in eastern Adriatic without having to establish a direct presence in the area.

Epilogue

Victory over the Illyrian brough financial benefits to the Roman Republic. Apart from the usual plunder, the Romans seized at least twenty Illyrian ships filled with booty from Peloponnesus. As for the nature of the Roman rule over the territories where they won there are two opinions. One stipulates that the Romans established a direct rule over the coastal Illyria. This resulted in a Roman protectorate that stretched from the Mati valley into the Vjosa valley. It included in the hinterland the territory of the Parthini and the Atintani. The other opinion suggests a loose relationship between the Romans and the new territories. The relation was based on the principle of Roman “amicitia”. Whatever the case, the Romans had gained a hold on Issa, Dyrrachium, Apollonia, and, especially important, Corcyra. With these bases, the Republic could monopolize the valuable and strategic sail across the Adriatic and Ionian Strait.

The First Illyrian War introduced the Roman Republic for the first time with Hellenic politics including mainland Hellas. Immediately following the victory, the Romans sent envoys to Athens and Corinth. The latter even invited them into the Isthmian Games. Back in Rome, the people honored the heroes. Pliny mentioned the statues of Publius Junius and Titus Coruncanius (Lucius Coruncanius ?), executed on Teuta’s orders, standing at the Rostra (Rome’s speaking podium).

Bibliography

Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Instituti i Historisë. Historia e Popullit Shqiptar, I, p. 137. Botimet Toena, 2002.

Appiani Alexandrini. Historia Romana. IV. Illyrike.

Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Instituti i Historisë. Historia e Popullit Shqiptar, I, p. 137. Botimet Toena, 2002.

Badian, E. (1952) Notes on Roman Policy in Iliria (230-201 B.C.). Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. XX, pp. 71-93.

Dell, H. J. (1967). The Origin and Nature of Illyrian Piracy. Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte, Bd. 16, H.3, pp. 344-358.

Dioniss Cassii Cocceiani. Historia Romana. Fragmenta.

Joannis Zonarae. Epitomae Historiarum. VIII.

Hammond, N.G.L. (1966). The Kingdoms in Illyria circa 400-167 B.C. The Annual British School at Athens, 61, 240-253.

Hammond, N.G.L. (1966). The Opening Campaigns and the Battle of the Aoi Stena in the Second Macedonian War. The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. LVI, Parts 1 and 2.

Hammond, N.G.L. (1966). Illyria, Rome and Macedon in 229-205 B.C. The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. LVIII, Parts 1 and 2.

McPherson, C.A. (2012). The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism. Library and Archives Canada = Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

Polybii. Historiae. II

Velija, Q. (2012). Mbretëri dhe Mbretër Ilirë. West Print.

Walbank, F.W. (1976). Southern Illyria in the third and second centuries B.C. Iliria, Nr. 4, pp. 265-272.

Wilkes, J. (1992). Ilirët (Illyrians). Bacchus, Tirana-Albania, 2005.