Second Illyrian War: Rome’s Show of Force in Eastern Front

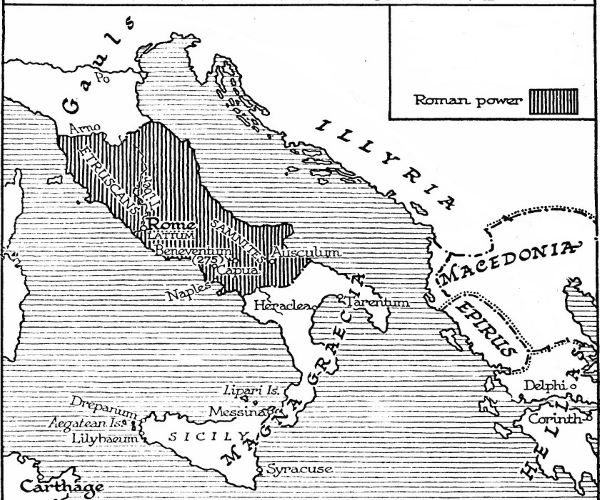

The Second Illyrian War was fought between the Romans and the Illyrians in 219 B.C.E. This war took place nine years after the First Illyrian War when the Romans first established a foothold on the Illyrian coast. As such, the Second Illyrian War was in continuation with the Roman expansion east of the Apennines.

Before the War

Rome before the Second Illyrian War

During the decade following the First Illyrian War, the Romans did not maintain military forces in the region. All their efforts were apparently concentrated on dealing with the Gauls and the Carthaginian threat. The absence of the Roman troops in Illyria after the First Illyrian War is a factor that led to the outbreak of the Second Illyrian War.

The war of Rome in Cisalpine Gaul continued from 225-222. The Insubres, the Boii, and the Gaesatae joined forces against the Roman settlers expanding beyond the Po valley. They won the first battle at Faesulae (Fiesole) though the Romans managed to preserve most of the army. At Telamon (apparently modern Poggio di Talamonaccio), the Romans won a resounding victory killing as many as forty thousand Gauls and capturing some other ten thousand.

Two years after Telamon, the Romans met the Gauls once again near River Addua (Adda). The Republican forces led by the consul Gaius Flaminius came up once again victorious. In 222, the consular army met another Gallic force in Clastidium (Casteggio). It marked a complete victory for the Romans whose consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus personally slew in combat the enemy general, Viridomarus of the Gaesatae. Complete victory in Cisalpine Gaul was marked by the Roman conquest of Mediolanum (Milan) in the territory of the Insubres.

Demetrius of Pharos before the Second Illyrian War

After the First Illyrian War, Demetrius of Pharos succeeded Teuta on the throne of Ardiaei. He was practically lifted in his position by the Roman Republic. The Romans thought of Demetrius to be the ideal client king over the Ardiaei. He had already helped the Romans begin at a significant advantage the First Illyrian War by delivering them Corcyra without a fight. Demetrius even acted as a native guide to the Roman army as they moved from Corcyra north.

Upon accession, Demetrius married Triteuta, the mother of the infant king Pinnes, thus establishing a firm authority over the Ardiaei. In his first year, he kept a low profile in interstate affairs, playing to the narrative of him preserving Roman interests in the region.

However, when Rome was busy with the war against the Gauls, Demetrius of Pharos engaged in independent action east, ignoring his supposed position of subservience toward Rome. The leader of the Ardiaei established an alliance with Macedon, a state already projected by the Roman Republic as a future enemy. From this alliance, the Ardiaean monarch benefited the possession of the strategic region of Dassaretis. At the same time, Demetrius persuaded the Atintati to detach themselves from the Roman protectorate and join his protection.

In 223, Demetrius of Pharos led a contingent of 1,600 soldiers against Cleomenes III of Sparta in Peloponnesus, as part of Macedon’s allies. A year later, this Illyrian force played an important role in Antigonus Doson’s victory at the battle of Sellasia. In early 220, Demetrius, along with the Illyrian general Scerdilaidas, sailed south of Lissus with about 90 ships (lembi). This force tried without success to conquer Pylos through the sea. After Pylos, Scerdilaidas separated from the joining venture and returned north. Meanwhile, Demetrius with his 50 ships carried his raids as far as the Cyclades.

The Case for War

In 221, the Roman Republic returned the attention east, specifically in north-east Adriatic. During 221-220, the Romans fought the so-called Istrian War. This brief engagement resulted in Rome expanding its control over the Gulf of Venice and inland from the Istrian peninsula into the Julian Alps.

In retrospect, Rome’s Istrian War was a natural continuation of the war in Cisalpine Gaul and a convenient prelude to the Second Illyrian War. Likely based on this retrospective Appian accused Demetrius of Pharos of cooperating with the Histrians in raiding Roman grain ships in the Adriatic. The accusation, likely not true, remained part of the Roman narrative on Demetrius’ culprit. However, Demetrius did actually sail south of Lissus in 220 and that was in breach of the treaty between Rome and the Ardiaean state; a treaty established after the First Illyrian War.

By 219, the Romans had seemingly pacified the Cisalpine Gaul. The Republic established two important colonies along the Po valley, Cremona and Placentia, to keep the defeated Gauls in check. Free from this frontier, Rome decided to wage war with Demetrius at full strength. As in the war ten years ago against Teuta, the Romans made no formal declaration of war to Demetrius and the Ardiaei. However, unlike Teuta, Demetrius of Pharos learned beforehand of the Roman approach and made adequate preparations.

A Tale of Two Cities

Demetrius adopted only delaying tactics against the Romans, aware that he could not face them in open battle. Instead, he awaited the Romans into locations when the enemy had to engage in siege tactics. Demetrius hoped that the Roman arms would fail in besieging maneuvers. As such, the monarch of the Ardiaei gave up most of the territory and concentrated his defense only in two strong locations: Dimal and his hometown of Pharos.

Dimal was a heavily fortified town located on a steep hill in south-central Albania. It was considered impregnable by the natives. It also occupied a strategic position that controlled the route along the sheep pastures of the Myzeqeja plain up to the sink between the Shkumbin and Seman Rivers. In short, the town had the necessary supplies to resist a long siege.

Pharos, on the other hand, stood at the northern extreme of the Ardiaean domain. The city was founded during the so-called second wave of Hellenic colonization, during 385-384 B.C.E. Both the main town and the whole island bore the same name. The town where Demetrius organized the defense corresponds to the modern Stari Grad of the Hvar island, Croatia.

The War

Conquest of Dimal/Dimallum

In the spring of 219, the Roman consul Lucius Aemilius Paulus (not to be confused with his namesake and son “Macedonicus”) landed on the shores of southern Illyria. We don’t know the actual size of his army but it’s reasonable to assume that he counted on a force no smaller than that used against Teuta; specifically 20,000 infantry, 2,000 horsemen, and 200 hundred ships was the size of Paulus’ army.

Upon landing, Paulus immediately decided to take Dimal as he thought that by defeating the strongest post of the Illyrians he would discourage their resistance. His strategy worked splendidly; within a week of siege, the Romans reduced Dimal to submission. Interestingly, the Romans did not destroy the settlement. Apparently, they intended to use it as a base for future expansion east, at the expense of Macedon.

Ad Pharos

Following the fall of Dimal, other regional communities approached the Romans and promised their allegiance. With Roman protectorate and southern Illyria under control, the whole Roman force set sail for Pharos, the only remaining place of resistance.

The citadel of Pharos had been strongly fortified. A large number of skilled soldiers were stationed within its walls, lacking none of the necessary warfare equipment. Demetrius had hoarded food supplies and thus had prepared the city for a long siege.

Wishing to avoid a prolonged siege, the Roman consul employed a diverse tactic. Accordingly, the Roman navy approached the island during the night and, covered by darkness, landed most of the troops in hidden, forested areas across the aisle. The consul himself, the next morning, with the remaining forces on board of only twenty ships sailed openly against Pharos’ harbor. With this approach the Romans intended to lure the enemy out of the city walls, distracting them from the other hidden forces ready to fall on them upon exit.

Battle of Pharos

The Roman maneuver was successful and Polybius tells us how the battle then played out.

“Demetrius, seeing the ships and contemptuous of their small number, sallied from the city down to the harbour to prevent the enemy from landing. On encountering them the struggle was very violent, and more and more troops kept coming out of the town to help, until at length the whole garrison had poured out to take part in the battle. The Roman force which had landed in the night now opportunely arrived, having marched by a concealed route, and occupying a steep hill between the city and the harbour, shut off from the town the troops who had sallied out. Demetrius, perceiving what had happened, desisted from opposing the landing and collecting his forces and cheering them on started with the intention of fighting a pitched battle with those on the hill. The Romans, seeing the Illyrians advancing resolutely and in good order, formed their ranks and delivered a terrible charge, while at the same time those who had landed from the ships, seeing what was going on, took the enemy in the rear, so that being attacked on all sides the Illyrians were thrown into much tumult and confusion. At the end, being hard pressed both in front and in the rear, Demetrius’ troops turned and fled, some escaping to the city, but the greater number dispersing themselves over the island across the country”. II. XVIII. XII.

Aftermath

With the Phareans overrun by the Romans, Demetrius escaped the field. He took a small boat placed in a secret location and with that sailed away. In Ambracia, he joined the retinue of the Macedonian king Philip V as a political exile and became one of his main advisors.

After conquering Pharos, the Romans plundered all the citadel and then, unlike Dimal, destroyed it completely. Then, the Republic sent a formal note to Philip V demanding from him Demetrius, Rome’s main foe of the Second Illyrian War. Yet, Philip, aware of Rome’s hostile behavior toward Macedon, refused to attend to the Roman request.

Following the victory over Demetrius of Pharos, the Romans did not further move against the enemy, which technically was the Ardiaean kingdom. Instead, the Republic enforced the same measures agreed after the First Illyrian War counting on the same loose alliances in the region. Although victorious, the Romans again preferred to stay away from a direct involvement in eastern affairs.

Lucius Aemilius Paulus was awarded a triumph for his victory in the Second Illyrian War. Three years later, he was among those murdered at the carnage of Cannae by the Carthaginians.

Bibliography

Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Instituti i Historisë. Historia e Popullit Shqiptar, I, p. 137. Botimet Toena, 2002.

Appiani Alexandrini. Historia Romana. Illyrike.

Badian, E. (1952). Notes on Roman Policy in Illyria (230-201 B.C.). Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 20, pp. 72-93.

Dell, H.J. (1967). Antigonus III and Rome. Classical Psychology, Vol. 62, No. 2, pp. 94-103. Published by: The University of Chicago Press.

Dell, H.J. (1967). The Origin and Nature of Illyrian Piracy. Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte, Bd. 16, H. 3. Pp. 344-358. Published by: Franz Steiner Verlay.

Dell, H.J. (1970). Demetrius of Pharus and the Istrian War. Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte, Bd. 19, H. 1. Pp. 30-38. Published by: Franz Steiner Verlay.

Dioniss Cassii Cocceiani. Historia Romana. Fragmenta.

Joannis Zonarae. Epitomae Historiarum. VIII.

Hammond, N.G.L. (1968). Illyris, Roma and Macedon in 229-205 B.C. Published by: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 58, Parts 1 & 2, pp. 1-21.

Hammond, N.G.L. (1989). The Illyrian Atintani, the Epirotic Atintanes and the Roman Protectorate. The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 79, pp. 11-25. Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies.

McPherson, C.A. (2012). The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism. Library and Archives Canada = Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

Polybii. Historiae. II.

Rawlings, L. (2017). The Gallic Wars, Northern Italy, 225–222 BC. Part IV. The Macedonian Age and the Rise of Rome. Wiley Online Library.

Velija, Q. (2012). Mbretëri dhe Mbretër Ilirë. West Print.

Walbank, F.W. (1976). Southern Illyria in the third and second centuries B.C. Iliria, Nr. 4, pp. 265-272.

Wilkes, J. (1992). Ilirët (Illyrians). Bacchus, Tirana-Albania, 2005.