Ancient Rhizon: A Typical Illyrian City and Royal Residence

The ancient city of Rhizon (corresponding to modern Risan in Montenegro) was located on the northernmost inlet of the modern Gulf of Kotor. This gulf was the one that the Venetians called the “Bocche di Cattaro” and what the Romans called the “Sinus Rhizonicus”. This gulf clearly took the name of the most important city on its shore; that city being Rhizon in ancient times. The area of Sinus Rhizonicus was composed of narrow fjords connecting two major enclosed gulfs (the Teodo and the papillon-shaped interior lagoon). It provided excellent shelter for native ships and indigenous nautical developments.

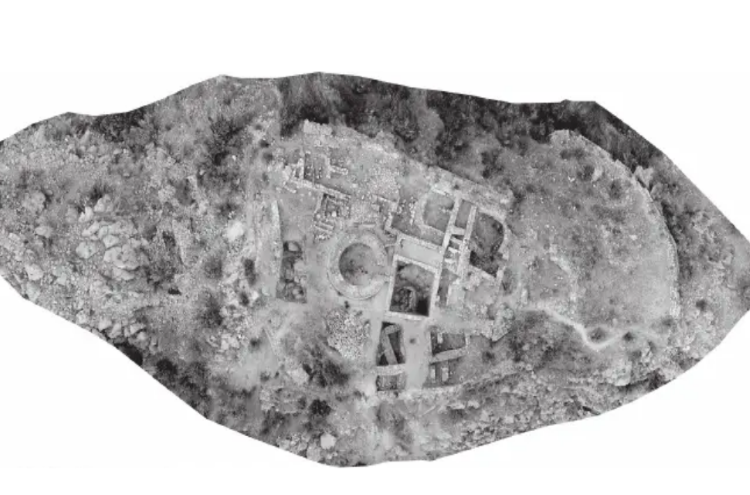

Urban Organization of the Ancient City

The territory of Rhizon was divided into insulae, building fortifications, and two main districts. The districts were the “upper city” (Gradi-na, 4.5 ha) and the “lower city” (Carina, 5.5 ha). This urban design, though sometimes getting Greek building terminology by scholars, is distinctly Illyrian in nature. The city was not organized in the fashion of the ancient Greek polis. Instead, it was designed as the seal of the local, Ardiaean chieftain who later extended his rule over other tribes and wider territories.

The upper city occupied a rocky slope 165 meters (540 feet) high covering a surface (without counting the acropolis) of 4.2 ha. In its highest part, a small plain opens up, the site of a small Medieval fortress, and, apparently, the location of the ancient acropolis. In the lower part, the section of the upper city communicates with that of the lower city through a single interior gate. The “upper city” seems to originate as early as the late VI century B.C.E. This was roughly the same time when Rhizon first appeared in literature, namely in the “Periplus” of Pseudo-Skylax. Yet, hardly any Hellenic sailor dared to enter into the imposing gulf, citing it from the outside as a black river; the gulf entered contemporary literature only in Roman time.

The Lower City

The lower city was enclosed by large walls first established during the late fifth or early fourth-century B.C.E. Its surface, totaling 5.5 ha, resembles the shape of a boomerang, 500 meters (1,640 feet) long and 200 meters (656 feet) wide. Natural barriers shaping this section are the shore of the bay on one side, the flow of river Rhizonus/Rhizontos on the other, and the hill sloped on its back. Archaeologists have identified three gates around this section; a simple interior gate, already mentioned, connecting it with the upper city; one gate along the riverbank leading to the river, and an eastern gate.

A Strategic Location

The eastern gate of Rhizon’s “lower city” allowed the entrance of the ancient via Adriatica which then continued out through the river gate. Indeed, Rhizon was located at an important road intersection. According to ancient itineraries (Tabula Peutingeriana and Itinerary of Ravenna), the coastal road from Aquilea to Kythera passed through Rhizon. Notably, after crossing into Epitauro (modern Cavtat), the road entered right through Rhizon through the eastern gate. It then continued out of the city passing the river gate to eventually reach Buthoe (Budva), Olcinium (Ulqin), Scodra (Shkodër), Dyrrachium (Durrës), and so on. From Rhizon’ acropolis, a rough mountainous road began that led into the Dalmatian highlands and Abdera.

The few towers fortifying Rhizon were smartly concentrated on the two outer gates (i.e. the eastern gate and the river gate). Because of the main cargo road passing through the gate, the towers also likely served as some sort of customs checkpoints. This arrangement, especially that of the eastern gate, reminds that of the ancient Antipatrea of the early fourth-century B.C.E. The entrances of both these Illyrian towns form a small fortified courtyard from within the gate.

Rhizon’s Royal Palace; Seat of Ballaios, Agron, and Teuta

The extant literary evidence reveals very limited information on ancient Rhizon. As such, scholars turn to archaeological findings to put together some of the missing pieces. An important discovery was made recently in Risan, that of a building complex that served as the royal residence for Ballaios, Agron, and Teuta. The first construction phase of this residence dates back to the mid-third century B.C.E. The main structure of the complex was a megaron.

Architectonic features of the megaron suggest it was the main office building of the complex. An interesting insight related to the “Illyrian megaron” suggests that it was apparently burned down during a very violent attack. Findings of sling projectiles of lead used in combat suggest that fierce fighting took place here. The floor of the megaron, as Dyczek (2019) puts it, revealed “many pieces of Hellenic tableware, fragments of terracotta figures, all covered with a thick layer of charcoal”. It was here where excavations discovered more than thirty coins inside a foundation deposit.

Coins of Ballaios, Founder of a Kingdom with Rhizon as Capital

Numismatics has provided valuable insights into Rhizon and its nearby area. These coins are generally classified into three groups: autonomous bronze coinage of the town itself; the so-called “coinage from the Rhizonic Gulf” in silver and, apparently, bronze; the royal coinage of king Ballaios (otherwise an obscure figure) in silver and bronze. A study of the coins suggest that the mint of Rhizon was active during the III and II centuries B.C.E. All coin findings are a testimony to a unique monetary system that developed quite early among the Illyrians. As such, it also suggests the presence of a sophisticated trade exchange network and a strong, centralized authority.

The most interesting of the coins discovered in Rhizon are those bearing the profile of a “king Ballaios”. Some seven thousand such coins, most originating from Rhizon, have been recorded including several dozen forged specimens (subaeratus or silver-coated bronzes). Up until recently, Ballaios was believed to have been a puppet king, a vassal of the Romans, that ruled during the mid-II century B.C.E. However, recent discoveries place his rule some a hundred years earlier.

Thus, Ballaios was likely the first founder of the multi-tribal Ardiaean kingdom with the center at Rhizon that Agron and Teuta then inherited. His kingdom extended from Pharos (Hvar) north into the northern coast of Albania south; the area that corresponds roughly to Pliny’s “Illyrii Prioprie Dicti” (“Illyria Proper”) mentioned in his Historia Naturalis.

Illyrian Monarchs of Rhizon

Ballaios as a king of the Ardiaei with a seat at Rhizon fits well into the recorded line of the Ardiaean kings; Baçe (2018) hints to a possible rule of Pyrrhus of Epirus over Rhizon though the arguments are weak. As such, Pleuratus, father of Agron, either directly succeeds him sometime during the 280s or rises in those same years as king in Rhizon after an intermediate ruler between him and Ballaios. In the 250s, Agron succeeded Pleuratus making the most of Rhizon’s natural harbor nearby wood resources to build a sizable fleet. Teuta, the widow of Agron, continued the policy for maritime supremacy from Rhizon until the Romans appeared on the scene.

During the First Illyrian War, Rhizon appeared as an important city and the royal seat of the Ardiaean monarchy. It was in Rhizon where queen Teuta organized the resistance against the Roman Republic. In the context of his narrative on the First Illyrian War, Polybius mentions Rhizon as a small but strongly fortified city where Teuta took refuge (Pol. II. XI. XVI.).

Roman Rule

The town of Rhizon continued to be the capital of the Ardiaean kingdom until Gentius transferred his seat in Scodra. In 167, immediately following the defeat of Gentius from the Romans and dissolution of the Ardiaean monarchy, a Roman garrison was placed in Rhizon under the command of C. Licinius (Livy. XLV. XVI. II). Only a short while later, the Romans (on Anicius instructions) divided the conquered Ardiaean kingdom into three parts. According to Livy, one of the districts was composed of the lands inhabited by the Rhizonitae (Rhizon and nearby area) as well as the Agravonitae and the Olciniatae (Livy. XLV. XXVI. XIII). Rhizon remained part of this distinct until, at least, a 146 B.C.E.

According to Pliny (HN. III. CXLIV), during Roman rule, Rhizon had the unclear status of oppidum civium Romanorum. During Pax Romana (27 B.C.E. – 180 C.E.) it went through another prosperous period. Many villas were erected and the population grew to 10,000 people.

A piece of interesting information from the late years of Pax Romana comes from the dedicatory inscription of Lambaesis (in current Algeria) dated in 172 C.E. It reveals the story of an unknown Roman legate of Legio III Augusta, a native of Rhizon, likely named Medaurus who participated in the Marcomannic Wars alongside emperor Marcus Aurelius. In the dedication, the author claims to have received the consulship of Africa Proconsularis; a fine example of the Rhizonitae integration in imperial high ranks.

Decline and Sack

Imperial strife and partitions affected Rhizon’s prosperous status as that of many other towns across the Roman empire. Especially, the division of 395 C.E. that placed Rhizon at the northwestern edge of the Byzantine Empire turned the city into a peripheral area. Disruptive invasions caused the decline of Rhizon until it was sacked by the Avaro-Slavs shortly after 595.

Bibliography.

Baçe, A. (2018). Qytetet dhe Qytezat Ilire dhe në Iliri. I. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Tiranë.

Dyczek, P. (2019). Illyrian King Ballaios, King Agron and Queen Teuta from ancient Rhizon. ANODOS, Studies of the Ancient World 13/2013. Trnava.

Morgan, D. U. (2004) (2014). Autonomous Coinage of Rhizon in Illyria. L’Illyrie méridionale et l’Épire dans l’antiquité IV, Actes du 4ème Colloque international de Grenoble (10-12 octobre 2002), ed. P. Cabanes et J.-L. Lamboley, Paris 2004.

Pliny. Historia Naturalis. III. CXLIV.

Polybii. Historiae. II. XI. XVI.

Titius Livi. Ab Urbe Condita. XLV. XXVI. XIII; XLX. XVI. II.