Battle of Heraclea: The Romans Find Their Match

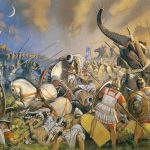

The Battle of Heraclea was fought in 280 B.C.E., between the forces commanded by Pyrrhus of Epirus and those of the Roman Republic led by consul Publius Valerius Laevinus. This battle was the first of the three major battles the renowned Epirote general fought against the Romans. It was also the first instance when the Romans encountered war elephants in battle.

Rome, Tarentum, and Pyrrhus before the battle

Rome before the battle

Prior to Pyrrhus’ arrival in Italy and the battle of Heraclea, the Romans had efficiently practised the concept that centuries later took the name “Lebensraum”. First fighting and conquering their neighbours, and then, the neighbours’ neighbours, they stretched into the Po valley north and in the heel of Italy south. In the latter frontier, the Roman conquest of Capua in Campania in 343 B.C.E. marked the beginning of the Roman advance. In between 326 and 290, the Romans fought with success the Samnites for control of central Italy.

By the early III century B.C.E., it was the turn of the Greek colonies at the heel of Italy to deal with the Roman imperial ambitions. The Roman rise in power included commerce too; commercial products produced from the interior were competing successfully with those produced in Magna Graecia. The Hellenic colonies here, lacking military strength, not only did not pose a threat to the Romans but even sought their help in fighting the native Lucanians. Thus, the colonies of Thurii/Thourioi (modern Sibari), Croton (Crotone), Locris (Locri), and Rhegion (Reggio Calabria), all placed themselves under Roman hegemony admitting Roman garrisons in their cities. Only the city of Tarentum (Taranto) or Taras tried to maintain its full independence.

Tarentum before the battle

In 333, Tarentum established a treaty with the Roman Republic where the latter agreed not to sail beyond Cape Colonna in Lacinium. Yet, on the pretext of reaching the city of Thourioi by sea, the Roman warships sailed across Magna Graecia, beyond Cape Colonna, practically breaking the treaty with Tarentum. At first, the Tarentines remained passive, but when a Roma navy of ten triremes approached their harbour and seeked anchorage, they revolted. The citizens of Tarentum assaulted all the nearby Roman ships, sinking four of them.

This incident brought the war between Rome and Tarentum into the horizon, but the latter, unlike the former, was unprepared for the military struggle. Thus, Tarentum sought assistance and salvation from abroad, finding the right leader in the figure of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus from across the Ionian Sea. Contacts between the Tarentines began in 283 and materialized in 281.

Pyrrhus before the battle

Before venturing at the aid of Tarentum, Pyrrhus had become in 297, king of Epirus, the region washed by the waters of the northern Ionian Sea. From then onward, he had ruled in the fashion of Hellenistic kings, pretending to best represent Alexander the Great. Accordingly, he invested heavily in recruiting mercenaries, made several attempts at gaining the throne of Macedon, and initiating major public works. He founded new cities such as Antigonea (modern Saraqinisht, named after his first wife Antigone) and Berenice (modern Kastrosikia, named after his first mother-in-law). Also, he declared Ambracia (Arta), conveniently located on the forefront of the major sea routes with Italy, as the new capital of Epirus. Meanwhile, he kept Dodona as the state’s spiritual center.

When embassies from Tarentum appeared at Pyrrhus court, the latter had just lost the throne of Macedon to Lysimachus. For an expedition against the Romans, Pyrrhus needed a substantial army that the remote areas of Epirus could not muster alone. Thus, he sought help from abroad securing financial aid from Antiochus I Soter, 30 ships for transport by Antigonus II Gonatas, and a substantial military force by his major ally Ptolemy Keraunos. The force provided by Ptolemy consisted of 5,000 Macedonian phalangites, 4,000 cavalry men (of note in this unit were the Thessalian riders), and 50 Indian elephants. After mustering additional units himself, Pyrrhus arrived in southern Italy in 280.

Position and Composition of the Pyrrhus’ army

After arriving with the main army in southern Italy, Pyrrhus marched out of his base at Tarentum with about thirty thousand men. Most of his troops he had brought with him from across the sea. They consisted of three thousand Thessalian cavalries, 3,000 advance troops, 20,000 infantry, 2,000 archers, 500 Rhodian slingers, and, of note, 20 Indian elephants (30 elephants short from the initial contingent). He lacked support from the locals, having only enrolled a contingent from Tarentum into his ranks.

The army of Pyrrhus advanced in the plain between Pandosia (modern Santa Maria d’Anglona, Tursi) and Heraclea (modern Policoro), southwest of Metapontum (modern Metaponto, Bernalda). Here, the conqueror smartly set out his camp with the river Siris (modern Sinnis) in front. In addition, a contingent of about 3,000 missile men was placed as guards on their side of the river bank. Himself with the main army Pyrrhus stood at a distance, with troops in relaxed mode. The Epirote king, giving any potential ally time to join him, had no reason to initiate a fight; yet, he would not avoid a battle if pressed by the enemy.

Position and Composition of the Roman army

The Romans, led by Laevinus, also arrived at the site via Lucania, setting up themselves at the other side of the river. They numbered some 40,000 soldiers, larger in size than the opposition. This Roman Republican army did not have professional soldiers in its ranks. The legionnaires that came to Heraclea were gathered for that occasion alone, on the spot so to speak. It would take another two hundred years for the Romans to establish full-time professional Roman legions. Now/however, that did not mean they were not strong fighters, on the contrary; they relied on strength and persistence more than strategy. Thus, they carried no reconnaissance prior to the battle, believing Pyrrhus’ elephants from their camp distance to be Lucanian buffalos.

The main unit of the Roman legion was the maniple. Distinct maniples formed three (or four) lines in the legions, each based on wealth, age, and fighting skills and experience. The soldiers of the front lines formed what was called the hastati, young men with no particular fighting experience. These were armed with a scutum (shield), pilum (throwing spear), and a sword/gladius. Against professional armies, the hastati would be able to only throw their scutum against the enemy.

In the following line, the principes, armed as the hastati but with stronger helmet and body armors, were somewhat more experienced. They commonly replaced the hastati in combat and some time changed places with them.

The third line, the triarii, was composed of war-torn veterans, often kept in reserve and engaged only in key moments. Armed with the hasta, they used these spears to thrust against the enemy and not throw it like the pilum.

The Battle

Initial Fight

The Romans, not much fond of tactical “chess play”, took the initiative first. They began crossing the river with their legionnaires at a fordable place. Their cavalry followed dashing through the rivers. This took the Pyrrhic river guard force by surprise. Overrun by the enemy, they fled to the main camp raising the alarm of the main army.

Pyrrhus responded by quickly leading himself 3,000 Thessalian cavalrymen into the enemy. “But when he saw a multitude of shields gleaming on the bank of the river and the cavalry advancing upon him in good order, he formed his men in close array and led them to the attack”. The Thessalians, then the best riders in the world, engaged and overcame the enemy. However, the Romans continued their crossing, engaging the Pyrrhic forces in mass numbers. The Epirote commander managed to halt the Roman infantry and cavalry advance until his phalanx approached and entered the fight.

In the chaos created at the front lines, Pyrrhus became dangerously involved. His horse followed by his companions came close to fighting distance with many from the enemy. Pyrrhus himself fought dressed in royal apparel distinct from the rest of his troops and even his companions. As such, enemies seeking glory would simply rush to kill the leader of the opposition.

Deeds of the Roman Allied Cavalry

From this point, the accounts describing the battle, and notably that of Plutarch, resemble Homeric poems. A Frentanian named Oplax, commander of a cavalry regiment from the Roman side threw his spear at the king and killed his horse. Leonnatus the Macedonian, a companion of the king, neutralized the risk by hitting Oplax’ horse, with the latter eventually killed on the ground. Pyrrhus also would have hit the ground hard had he not been saved by his surrounding bodyguards.

Pyrrhus, aware that his garments were to his detriment, gave “his cloak and armor [including his helmet] to one of his companions, Megacles” (Plu. Pyrrhus. XVII. I). The king himself went into back lines pushing the phalanx forward, pressing into an enemy with backs on the river. Now, the Romans, initially exploiting the surprise element, were paying for the inferior position on the battlefield.

Changing his clothing proved vital if we are to believe the narratives of Plutarch and that transmitted by Joannis Zonarae. Thus, when the Pyrrhic forces were dominating the enemy, killing many and throwing others back into the river, an event risked these gains. Many of the enemies attacked Megacles, now carrying the royal clothes. A certain Dexous slew him took his helmet and cloak, and “rode up to Laevinus, displaying them, and shouting as he did so that he had killed Pyrrhus…there was joy and shouting among the Romans…until Pyrrhus, learning what was the matter, rode along his line with his face bare stretching out his hands to the combatants and giving them to know him by his voice”. (Plu. XVII. II-III).

Unleash of the Beasts

Seeing Pyrrhus alive and well, Laevinus ordered all his reserve cavalry to engage and try to outflank the enemy. Determined to avoid further surprises and prevent outflanking, Pyrrhus ordered the launch of his elephants, until then kept in reserve.

The Roman consul, learning of the opposing beast not much prior to the battle, may have tried to calm his fellow soldiers. For example, when it came to facing opposing cavalry, Roman generals often instructed their soldiers not to fear the animal rather deal with the ones riding them. And they were right; war horses ride the battlefield usually without smashing and stomping into humans. However, that’s not true for war elephants. Once deployed into battle, a war elephant will try to fatally hit with its tusks and trunk and stomp with its feet every human in its way.

The Romans, never having faced elephants before realized their immense power the hard way. Zonara confirms bafflement not that different than that experienced by the French when they faced the first English tanks in 1916 at the Battle of the Somme. Accordingly, “…at the sight of the animals, which was out of all common experience, at their frightful trumpeting, and also at the clatter of arms which their riders made, seated in towers, both the Romans themselves were panic-stricken and their horses became frenzied and bolted, either shaking off their riders or bearing them away…the Roman army war turned to flight, and in their rout some soldiers were slain by the men in the towers on the elephants’ backs, and others by the beasts themselves, which destroyed many with their trunks and tusks (or teeth) and crushed and trampled under foot many more”. (Zonara. VIII. III).

At the point of elephant charge, while Roman horses went rogue, Republican foot soldiers had no capacity of dealing with the beasts either. The gladius, the short stabber then common among all Roman soldiers, had no effect on the opposing elephants. In a short time, the whole Roman army went into a massive and chaotic retreat. Many of them fell trying to leave the battlefield chased by the Thessalian cavalry.

Aftermath of the Battle

Despite the tendency of Roman literary tradition to turn the narrative in their favor, the battle of Heraclea ended in a decisive, splendid victory for Pyrrhus. On the casualties, Plutarch mentions two authors as sources to his narrative. According to Dionysius, as transmitted by Plutarch, there fell fifteen thousand on the Roman side and thirteen thousand on the side of Pyrrhus. According to Hieronymus of Cardia, as again transmitted by Plutarch, seven thousand Romans fell on the battle while less than four thousand fell from the side of Pyrrhus. The figure based on Dionysius counting the casualties suffered by Pyrrhus is clearly exaggerated while that of Hieronymus is more realistic. Yet, Hieronymus also kept casualties on the Roman side at a low seven thousand in what could have been a more costly defeat for the Republic.

The battle of Heraclea, beyond victory on the field, also marked a political and strategic victory for Pyrrhus. Thus, acting on the news of a Pyrrhic victory, the Hellenic colonies of southern Italy (especially Locris and Croton) now rallied to the side of the Epirote, abandoning their ties with the Romans. Also, the indigenous populations of the Samnites and the Lucanians officially declared themselves on the side of Pyrrhus. After receiving these new allies Pyrrhus could expand his territory of safe march and secure a reliable supply line that stretched at a greater distance. More importantly, he quickly replaced his losses by drawing troops from the new allies and even increasing the size of his army.

With the inflated army, Pyrrhus moved north, as far as Praeneste (modern Palestrina), only 37.5 kilometers (about twenty miles) from the city of Rome itself. After circuiting around Campania, Pyrrhus retreated to winter in Tarentum.

Bibliography

Aeliani, Claudii. De Animalium Natura.

Cross, Geoffrey Neale (1932). Epirus, A study in Greek Constitutional Development.

Diodori. Bibliotheca Historica.

Dionis Cassi Cocceiani. Historia Romana.

Dionysi Halicarnassensis. Antiquitatum Romanarum.

Flori, L. Annaei. Epitome.

Frontini, Julii. Stratagematon.

Iustini, M. Iuniani. Epitoma. Historiarum Philippicarum.

Pausaniae. Descriptio Graeciae.

Plutarch. Life of Pyrrhus.

Pyrrhus of Epirus and the Roman Republic. Retrieved from: https://erenow.net/ww/warfare-in-the-classical-world-an-illustrated-encyclopedia/8.php?fbclid=IwAR2e3S6PD9w0MUYiNP9ADquEh4wXEOc03UattZz1IVdn7xt4SV-9G4TMeew.

Recaldin, J. (2010). Pyrrhus of Epirus: Statesman or Soldier? An analysis of Pyrrhus’ political and military traits during the Hellenistic Era.

Man, K. (2018). Pyrrhic Wars: Heraclea Battle. Retrieved from: https://kmhistories.wordpress.com/2018/08/21/heraclea/.

Montanelli, I. (1997). Historia e Romës (Storia di Roma). BESA.

Strabonis. Geographica.

Zonarae, Joannis. Epitomae Historiarum.

Under Pyrrhus, the Epirote Army soon transformed into a significant military force thanks to the major use of contingents provided by allies or mercenaries. When the ambitious king landed in Italy, his expeditionary army comprised the following: 17,500 infantrymen, 2,000 archers, 500 slingers, 2,400 cavalrymen and twenty war elephants. It is interesting to note that Pyrrhus was strongly supported by Ptolemy Keraunos during the organization of his Italian expedition: the usurper of Seleucos’ dominions and army sent him the twenty war elephants, 400 cavalry and 5,000 infantry, all veteran soldiers. Of these, 2,500 were Macedonian phalangists and 2,500 excellent asiatic light troops. The heavy infantry of the Epirote Army was completed by 3,000 phalangists from the city of Ambracia (the only significant urban centre of Epirus, conquered by Pyrrhus, who made it the new capital of his kingdom) and 9,000 `real’ Epirotes (Molossians, Chaonians and Thesprotians) also equipped as phalangists. The 9,000 Epirotes were also organized into three different units of 3,000 men, corresponding to the three main tribal groups of Epirus. The remaining 3,000 infantry were all lightly equipped Greek mercenaries: Aitolians, Athamanians and Acarnanians. The 2,400 cavalry comprised 1,700 heavy cavalrymen from Epirus and 700 light cavalrymen. The 1,700 heavy cavalry was formed by the aristocracy of the kingdom, as in Macedonia, apparently comprising an elite royal squadron of 500 men (acting as the mounted bodyguard of the king) and four `line’ squadrons with 300 soldiers each. The 700 light cavalry included 300 Thessalians and 100 Macedonians sent by Ptolemy Keraunos and 300 Greek mercenaries (Aitolians, Athamanians and Acarnanians). After its arrival in Italy, the army was supplemented by the military forces of Taras and large numbers of allied/mercenary Italic warriors from several different peoples.