Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus of Epirus: Lineage and Character

Pyrrhus of Epirus (also known as Pyrrhus I, Pyrrhus, or Phyrrhus), was born in 319/318 B.C.E. in Epirus. He was the son of Aeacides, king of Epirus (ruled 331-316, 313) part of the ruling Epirot tribe of the Molossians, and Phthia, a noblewoman from Thessaly, daughter of Menon. Pyrrhus was also the second-cousin of Alexander the Great of Macedon (ruled 336-323). Pyrrhus is, albeit unfairly, mostly known for the term “Pyrrhic victory” coined after him to refer to a victory achieved at a great cost.

Pyrrhus was set alongside Caius Marius, the army reformer of the late Roman Republic, in Plutarch’s “Parallel Lives” (“Vitae Parallelae”). Plutarch provides the most information we have on Pyrrhus and his deeds but the source should be treated with reserves.

Pyrrhus was quite a character. He was at any standard unusually tolerant, especially among his subject in Epirus. We are told that he laughed at complaints that some young fellows made against him and dismissed them without punishment. On another occasion, he refused to banish an Ambracian from Epirus although the later had openly opposed his authority.

Pyrrhus had a chivalrous conduct that is reflected in his fightings. He was concerned with defeating the enemy and not slaughtering it. We are told by Frontinus (II, VI, X) that he instructed his generals not to pursue the enemy into retreat. Pyrrhus argued that his armies should leave to the enemy an open way into retreat, so that the enemy actually felt tempted in retreating and thus saving both sides from further losses.

Pyrrhus believed that a king should focus most on military matters and delegate other duties to others. He had a habit of engaging himself in the fights thus risking his life many times in combat.

A strange thing about Pyrrhus’ appearance was that he had some kind of mutation that made his upper jaw look like a continuous bone. This would have made him look more fierce rather than knightly.

Pyrrhus’ ventures suggest that he was an adventurer and explorer more than he was a politician. In key moments he did not focus on what he had already gained but instead went pursuing another target. Yet, in fightings he was one of the best generals and the greatest tactician, comparable with figures such as Hannibal, Scipio, and, of course, Alexander the Great.

At that time, comparisons with Alexander were common and each ruler attempted to copy or model him in some way. Yet, according to Plutarch, Pyrrhus had an authentic vigour and military prowess that naturally matched that of Alexander. According to the author “the other kings…represented Alexander with their purple robe, their body-guards, the inclination of their necks, and their louder tones in conversation; but Pyrrhus, and Pyrrhus alone, in arms and action”.

Childhood Troubles

Pyrrhus’ royal inheritance and even his life were threatened just after he was born, by Cassander, then regent king of Macedon (ruled 305-297). Through Cassander’s interference, Aeacides was expelled from the throne and replaced for a while by his uncle Neoptolemus II (ruled 302-297, co-ruled 297-295). Aeacides’ family was persecuted and many of his friends were killed. Infant Pyrrhus was saved by a group of pro-Aeacidians and sent north, via Megara, into the court of the Illyrian king Glaucias (335-302). The Epirot embassy asked Glaucias to keep the child under his supervision.

At the time Pyrrhus was sent to Glaucias for protection, the Illyrian king had already established friendly relations with the Epirot monarchy of the Aeacides. He had married Beroea, a Molossian princess who, as Pyrrhus, was part of the Aeacides family. Beroea seems to have encouraged Glaucias to take the child under custody even though that meant drawing in Cassander’s aggressions. Thus, Glaucias took the child, adopted it, and raised it in a fashion worthy of a monarch. The Illyrian even resisted Cassander’s bribes to hand the child over to him.

In 306, when Pyrrhus had reached the age of twelve, Glaucias marched into Epirus. There he crushed any pro-Macedonian opposition focused around king Alcetas (ruled 313-306) and restored his adoptive son into the throne. After leaving suitable guardians to assist the new young king into his affairs, Glaucias returned into his domain.

Pyrrhus first period of reign was short. After just four years, Pyrrhus would travel north responding to a royal weeding invitation of Bardylis II “the Younger”. Cassander used his absence to incite revolt among the Molossians who replaced Pyrrhus with Neoptolemus II.

Eastern Adventures

Banished from his kingdom, Pyrrhus joined his then brother-in-law, Demetrius Poliorcetes (“the Besieger”) (ruled 294-288 B.C.E.) into his ventures. Pyrrhus followed Demetrius in Asia where they joined the army of Antigonus I Monophthalmus (“the One Eyed”) (successor king who ruled during 306-301), Demetrius’ father. It was here where Antigonus presumably said that Pyrrhus would be the greatest general of the time when he reached maturity.

Both Demetrius and Pyrrhus fought in support of Antigonus at Ipsus. Pyrrhus positioned alongside Demetrius in the cavalry unit on the right wing. Ultimately, Antigonus would lose the battle after 500 elephants of Seleucids crushed his side. Pyrrhus himself would suffer from the elephants of the enemy that forced him and his unit into retreat.

Although participant in a defeat, Plutarch praises Pyrrhus for leading a brave charge against the opponents in his front and making a “brilliant display of valour among the combatants”. With the remaining of the troops, both Demetrius and Pyrrhus retreated safely into Greece. Here, Pyrrhus was appointed as a governor responsible for the control and defence of the cities of Megara and Corinth, Corinthian isthmus, and portions of Achaea and Arcadia, while Demetrius was away in Asia Minor.

In 298 B.C.E., Demetrius and Macedonian king of Egypt Ptolemy I Soter (ruled 323-282 B.C.E.) agreed on a peace treaty. The treaty specified that Pyrrhus must be sent as hostage (actually more like an honourable guest) at Ptolemy’s realm. Most sources, ancient and modern, support the view that Pyrrhus offered himself as hostage. Rather than this, it is more plausible to think that Ptolemy handpicked Pyrrhus to turn him into his custody. The ruler of Egypt was present at Ipsus and must have noticed the military might and potential Pyrrhus possessed. In time, there was no reason why Ptolemy could not make use of Pyrrhus’ services. After all, Pyrrhus was a Molossian, a legitimate successor of the royal line of Epirus. Thus, it would be easier for Ptolemy to restore Pyrrhus in Epirus for the purpose of counteracting the powers of Cassander and Demetrius there.

Accordingly, in 297 B.C.E., Pyrrhus arrived at Alexandria, the formidable centre of the Ptolemaic kingdom. At Ptolemy’s court, Pyrrhus further distinguished himself as a virtuous man, excelling in hunting and bodily exercises among other disciplines. Moreover, Alexandria must have been the ideal place for him to further his knowledge on military tactics and leadership. Pyrrhus may have also worked with Indian war elephants in Alexandria as there were a few dozens of such animals there, captured from Perdiccas III (ruled 365-360 B.C.E.).

Pyrrhus soon befriended Berenicé, whom he recognized to be Ptolemy’s most influential wife. Ptolemy himself reassured his initial hunch of Pyrrhus being a worthy investment. For Pyrrhus, this whole venture paid dividends when he was selected among many candidates to marry Antigone, a daughter Berenicé had from a previous marriage.

King of Epirus

In 297, Ptolemy decided to interfere in Epirus. He supplied Pyrrhus with ships and a mercenary force. Along with troops, Ptolemy supplied Pyrrhus with monetary aid in the form of copper coins minted in an “Epirot” style so that they could easily be introduced in Epirus. In charge of this force, Pyrrhus sailed back to Epirus.

When Pyrrhus arrived at Epirus, the inhabitants welcomed him; a natural behavior as their former leader had now returned at the head of a significant army. Neoptolemus was still on Epirus’ throne. Pyrrhus moved cautiously not to drive his rival out.

Some argue that the Molossian showed hesitance to remove the rival because of potential assistance that his rival could receive from one of the “successors” such as Cassander or Demetrius. However, contextualization is needed here. At the time Pyrrhus returned, both Cassander and Demetrius were in no position to interfere in Epirus. On the contrary, Ptolemy and Agathocles of Syracuse (ruled 317-289) besieged and captured Corcyra at the expense of a weak and ill Cassander. On the other hand, Demetrius was campaigning in Asia at this same time. This means that the position of Pyrrhus was more than secure from any foreign interference. The explanation that remains is that Pyrrhus acted with an initial tolerance towards his rival because he wanted to first establish his reputation among the subjects. It may be that Pyrrhus himself encouraged his citizens to view him as adherence to peaceful resolutions. That policy would have suited his character well.

However, it was clear that only one of the co-rulers would stand in control of Epirus. Pyrrhus’ followers were not happy to share the rule with another and pressed their leader to move against Neoptolemus. Moreover, the latter may have attempted to execute Pyrrhus. Apparently, it became a matter of who would kill the other first.

According to Plutarch, who seems to follow in this case a narrative in favor of Pyrrhus, Neoplolemus was the first to attempt to get rid of his opponent. His narrative takes the reader into a journey of a livestock-based society and a range of otherwise unknown characters. Accordingly, Gelon, a supporter of Neoptolemus approached Myrtilus, Pyrrhus’ cup-bearer, and proposed that he turn into a follower of Neoptolemus and kill Pyrrhus by poison. Myrtilus pretended to accept Gelon’s proposal but soon after, reported the machination to Pyrrhus. To confirm the plot, Pyrrhus infiltrated Alexicrates, his chief cup-bearer to Gelon’s circle. The conspirators thought that everything was going according to plan and apparently lowered their guard. It became clear that the conspiracy had been ordered from Neoptolemus himself. The latter was heard speaking about it at his sister Cadmeia’s house by Phaenarete, wife of Samon who managed Neoptolemus’ flocks. Phaenarete heard Neoptolemus’ prattle and reported it to Pyrrhus wife, Antigone. This gave Pyrrhus enough evidence to move radically against Neoptolemus. Behaving as usual, Pyrrhus invited Neoptolemus at a banquet. At this private gathering, Pyrrhus had him killed. It was the year 295 and Pyrrhus had become the sole ruler of Epirus. It was also the year when his wife Antigone brought him a son, named Ptolemy (and a daughter named Olympias II). Pyrrhus had also secured his bloodline. Antigone herself did not survive childbirth.

A Hellenistic King

After Antigone, Pyrrhus decided to marry multiple wives to secure his kingdom. Hellenistic kings often engaged in polygamous marriages in order to achieve their political goals, and Pyrrhus was no exception. In about 294, Pyrrhus married Lanassa, daughter of Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse. From this marriage, Pyrrhus received the possession of Corcyra and Leucas, as his wives’ dowry. Corcyra especially was an important annexation as it had important trade links with the Greek cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily. It could also serve as a base for a military expedition across the Ionian Sea. In 292, or sometime between 287-284, Pyrrhus married another wife, the daughter of king Audoleon of Paeonia (ruled 315-286) (this Paeonian wife remains nameless).

At about the same period, Pyrrhus married Bircenna, daughter of king Bardylis II the Younger (the marriage whom he had attended years before when it cost him his throne). The marriage with the Illyrians not only secured Epirus from the north but also gave way to Pyrrhus ambition in this area. Meanwhile, the marriage with the Paeonians, who bordered Macedon in its north, allowed Pyrrhus to intervene in Macedon safely and with secured supply lines. It essentially turned Paeonia into a buffer state between Epirus and Macedon. Pyrrhus influence there would threaten the position of Demetrius when he became king of Macedon.

Lanassa brought Pyrrhus another son, Alexander, giving him a claim in Sicily. With Bircenna he had the youngest son named Helenus. It seems that Pyrrhus made sure his sons were raised to become brave fighters competent in military affairs.

With Epirus under his grip and borders secured, Pyrrhus could aspire to achieve important imperialistic goals, worthy of his might. His first target would be the cracked Macedon. Casander had passed away in 297 followed two months by his oldest son and successor, Philip IV (ruled 297 B.C.E.). Cassanders’ other sons Alexander V (co-ruled 297-294) and Antipater II (co-ruled 297-294) began rivaling over their fathers’ ruling legacy. Initially, their mother Thessalonice, who favoured Alexander, tried to manage the situation by dividing the kingdom into two parts: Antipater took possession of the western part up to the river Axios (Vardar) while Alexander took the eastern part. Yet, in 294 the outraged Antipater, who wanted the whole kingdom for himself, killed his mother and overrun his brother’s eastern part. With his position seriously threatened, Alexander asked for the assistance of Demetrius and Pyrrhus. The king of Epirus was the first and the only one to respond.

Macedonian Ambitions and Expansion

Pyrrhus had no other engagements at the time and may have interfered in Macedon even without the request of Alexander V. Dion Cassius in his “Historia Romana” (Book IX, Fragmenta XL, I) mentions that Philips IV “paid court to him (Pyrrhus)”. This line is usually overlooked by scholars but if true it would mean that Pyrrhus had a relationship of alliance with Philip IV before the later’s demise from a wasting disease at Elateia (modern Elatia). This would give Pyrrhus a legitimate claim over a divided Macedon. Yet, rather than acting on this sole pretext, Pyrrhus used Alexander V’ plea to gain as much as he could from the weak Macedonian ruler. The weak position of this Alexander only added to Pyrrhus’ bargaining power.

In exchange for his support, Pyrrhus demanded from Alexander the possession of the old Macedonian provinces of Tymphaea, and Parauae, as well as Amphilochia, Acarnania, and most important of all, Ambracia. Alexander, being in no position to negotiate, accepted Pyrrhus demands. From all these regions, Ambracia would be Pyrrhus most valuable addition. The Ambracian Gulf offered a naturally protected harbor for domestic fleets and a secure trading port. The region would contribute mostly to Pyrrhus efforts on increased overseas trade. Moreover, the area was already prosperous, different from the other rough and remote regions of Epirus. Its population provided Pyrrhus with a new and welcomed source of taxation, more resources, and more home-based military recruits.

Pyrrhus declared Ambracia as his new capital. However, he also promoted Dodona as the state’s spiritual center. The city may have even gained some administrative status under the rule of Pyrrhus. Pilgrims visited Dodona frequently and thus were a constant source of income to Epirus.

Thus, in 294, Pyrrhus moved into the promised regions, put them under his control, and put garrisons in their towns. He also advanced further into Macedon and was able to restore the balance between the brothers. Pyrrhus intervention caught the attention of Lysimachus (305-281) who felt obliged to act in favor of Antipater. He forged a letter from Ptolemy to Pyrrhus where the Epirot king was required to retreat from Macedon in exchange for a payment of three hundred talents from Antipater. Pyrrhus realized Lysimachus’ trick as soon as he read the opening line: “King Ptolemy, to King Pyrrhus, health and happiness” (A true letter from Ptolemy would address him “The father, to the sun, health and happiness”,).

Although Pyrrhus reviled Lysimachus for the fraud attempt, he was in favor of peace negotiations with Alexander V and Antipater II. Pyrrhus must have hoped on a peace that would keep the two brothers rule over a divided Macedon; and a divided Macedon would be ideal for him to potentially intervene there again in the upcoming years. Also, a divided Macedon would keep Demetrius away from interfering in Macedon after he had concluded his campaign in Peloponnesus. Moreover, a divided Macedon would give Pyrrhus some legitimacy over the Macedonian throne originating from a probable pseudo-legal relation he had with Philip IV; a legitimacy that he would not have over an otherwise united Macedon.

Yet, Pyrrhus was hesitant to become part of a multilateral peace treaty even though he favored a divided Macedon. Initially, he entered the peace negotiations with Lysimachus and Antipater but after the sides were met to ratify this treaty, an incident with one of the sacrificing animals parading through the crowd offered Pyrrhus the excuse to relieve himself from the treaty. The Epirot king was aware that Demetrius was marching north from Greece in order to intervene in the affairs of Macedon. Pyrrhus perceived the changing political circumstances and thus rightly decided not to be tied to a treaty that would prevent him from challenging Demetrius if the latter made attempts to seize the Macedonian throne.

Pyrrhus retreated in Epirus, and may even have accepted Lysimachus compensation of three hundred talents promised in the forged letter. Eventually, Lysimachus alone was able to settle peace between the brothers; also an indirect victory for Pyrrhus policy of a divided Macedon. However, all the diplomacy fell apart when Demetrius murdered Alexander V at Larissa in the summer or autumn of 294. The victim had before gone out to greet Demetrius, whom he had previously asked help from (even to thank him for the help although Demetrius had not aided him!). At a banquet, Demetrius had Alexander murdered, in what seems a repetition of Neoptolemus’ murder by Pyrrhus. Demetrius, unopposed, declared himself king of Macedon.

Fighting Demetrius the Besieger

The marriage of Pyrrhus with Lanassa was a short one. In 290, Lanassa ran away from Epirus and went into the court of Demetrius to whom she married. Not only did Pyrrhus lose his wife, but with her, lost his wife dowry namely the possession of the valuable Corcyra and potentially Leucas. Corcyra turned under the possession of Demetrius. After these events, the tensions between Demetrius and Pyrrhus reached the highest level. Soared by Demetrius’ marriage with his previous wife, Pyrrhus had now a personal quarrel with Demetrius.

In 289 B.C.E., Demetrius overrun Aetolia and threatened the southern border of Epirus. Pyrrhus decided to counteract in order to prevent a Macedonian invasion of Aetolia which would leave Epirus vulnerable to enemy incursions from the south. With his army, Pyrrhus marched south while the Demetrius’ army was marching north. The two armies bypassed each other because of the different ways that had taken. Rather than turning back to follow Demetrius who was advancing in his kingdom, Pyrrhus continued his advance north. He knew that possession of Aetolia was the key to re-securing his kingdom. If Demetrius army hoped to gain hold of Epirus he needed to have Aetolia under his belt to ensure his supply lines.

Demetrius had already left Pantauchus in Aetolia with the task of garrisoning the region. Demetrius himself began plundering the southern Epirus. On the other hand, Pyrrhus arrived in Aetolia and came into contact with the 10,000 strong Macedonian armies of Pantauchus. Pyrrhus forces were about twice as large as those of Pantauchus.

According to Plutarch, Pantauchus was “the best of the generals of Demetrius for bravery, dexterity, and vigor of body”. The author’s narrative describes Pyrrhus actions in this battle, similar to a Homeric hero.

The two sides joined into battle where “there was a sharp and terrible conflict between the soldiers who engaged, and especially also between the leaders. For Pantauchus…challenged Pyrrhus to hand-to-hand combat; and Pyrrhus, who yielded to none of the kings in daring and prowess, and wished that the glory of Achilles should belong to him by right of valor rather that of blood alone, advanced through the foremost fighters to confront Pantauchus. At first, they hurled their spears, then, coming to close quarters, they plied their swords with might and skill. Pyrrhus got one wound, but gave Pantauchus two, one in the thigh, and one along the neck, and put him to flight and overthrew him; he did not kill him, however, for his friends hauled him away. Then the Epeirots, exalted by the victory of their king and admiring his valor, overwhelmed and cut to pieces the phalanx of the Macedonian, pursued them as they fled, slew many of them, and took five thousand of them alive”. (Plutarch, Pyrrhus, VII). The five thousand captured soldiers were promptly released by Pyrrhus in what seems to be a gesture of promoting him as a merciful leader.

After this severe defeat, Demetrius and his remaining Macedonians were forced to retreat from southern Epirus and Aetolia. In the autumn of that same year, Pyrrhus took the initiative and invaded Macedon as Demetrius had fallen ill. His forces advanced through Berroia (modern Veria) and reached as far as Edessa without encountering any opposition. When Demetrius recovered he was able to organize the defenses and repelled Pyrrhus at Aigeai (modern Vergina, Veroia). The Epirot returned into his secure domain.

Plutarch treats this easy advance into Macedon from Pyrrhus as mainly for pillaging purposes. Here, Plutarch draws from another author, Hieronymus, who maintained a pro-Antigonid view. Thus, Plutarch’s claim should not be taken at face value. Rather, it seems that Pyrrhus’ invasion was for the purpose of capturing new territories rather the plundering alone.

Victory against Demetrius gained Pyrrhus the nickname “Eagle” among his soldiers and followers. To the soldiers calling him Eagle, he responds: “Through you, I am an eagle, for how should I not be when I have your arms to sustain me”.

Pyrrhus proved a tough opponent for Demetrius. The latter had begun preparations for a campaign in Asia but could not take this venture without first having the back of his domain secured. Thus, in December, he reached a peace deal with Pyrrhus before his prepared campaign.

King of Macedon

The peace agreement dissolved in the next campaign season of 288. This time, Pyrrhus joined the alliance of successors against Demetrius. The alliance included Ptolemy Soter, Seleucus I Nicator (ruled 311 to 281), and Lysimachus. Ptolemy in command of his fleet decided to assault Demetrius’ possession in southern Greece. Meanwhile, Lysimachus and Pyrrhus made coordinated efforts by assaulting Macedon from different fronts at the same time. Lysimachus assaulted from his Thracian possession, while Pyrrhus moved east to occupy lower Macedonian territories. Demetrius could only respond to one of the threats and decided to move against Lysimachus. Meanwhile Pyrrhus, unopposed took possession of Beroea. He stationed the largest part of his army in Beroea while his companions moved against other Macedonian lands. On the northern front, Demetrius defeated Lysimachus and hastily moved back into the lower Macedon to repel Pyrrhus. The two sides met at Beroea where they pitched camps against one another.

Pyrrhus had used Demetrius’ absence to gain the favor of the Beroeans and even turn them against Demetrius. It seems that the Epirot was in friendly territory. He decided to use his influence and infiltrated spies into the enemy camp to cause confusion and turn them against Demetrius. These spies “pretended to be Macedonians, and said that now was a favorable time to rid themselves of Demetrius and his severity, by going over to Pyrrhus, a man who was gracious to the common folk and found of his soldiers…Some of the Macedonian, therefore, ran to him (Pyrrhus) and asked him for his watchword, and others put garlands of oaken boughs around their heads because the saw the soldiers about him garlanded” (Pyrrhus, XI) After a significant part of his army defected to Pyrrhus, the situation became dangerous for Demetrius. Pyrrhus had won without a fight and Demetrius, to avoid being killed by his own remaining soldiers, left the camp disguised as a simple soldier. Thus, Pyrrhus seized the enemy camp without a clash and was proclaimed king of Macedon (year 297).

Soon after Pyrrhus seized the Macedonian kingdom, Lysimachus appeared in the country and claimed that the expulsion of Demetrius was made possible by his contribution as well. Following his logic, Lysimachus claimed that half of Macedon belonged to him. Pyrrhus, who knew that was inferior to Lysimachus’ large forces and that had not strong authority across Macedon, accepted the proposition. Thus, the rule over Macedon was divided between them. Apart from Lysimachus’ superior force, another fact that influenced Pyrrhus’ resolution was that Lysimachus, unlike him, was of Macedonian descent and had with him Antipater, the remaining legitimate ruler of Macedon.

Pyrrhus had established his goal of creating a divided Macedon but now he was a direct rather than an indirect player in this division. Pyrrhus and Lysimachus were now direct neighbors and during the Hellenistic period that often meant war between them. Plutarch describes this war-like behavior of the diadochi: “Shortly afterward, they (Pyrrhus and Lysimachus) perceived that the distribution (of Macedon) which they had made did not put an end to their enmity, but gave occasion for complaints and quarrels. For how men to whose rapacity neither sea nor mountain nor uninhabitable desert sets a limit, men to whose inordinate desires the boundaries which separate Europe and Asia put no stop, can remain content with what they have and do one another no wrong when they are in close touch, it is impossible to say. Nay, they are perpetually at war, because plots and jealousies are parts of their natures, and they treat the two words, war, and peace, like current coins, using whichever happens to be for their advantage, regardless of justice; for surely they are better men when they wage war openly than when they give the names of justice and friendship to the times of inactivity and leisure which interrupt their work of injustice” (Plutarch, Pyrrhus, X).

Visit in Athens; Turning Tables

Pyrrhus tried to maintain his Macedonian possession by diminishing the influence of Demetrius in this region. When Demetrius sieged Athens, Pyrrhus advanced south to relieve the siege. Upon hearing on Pyrrhus’ approach, Demetrius abandoned the siege and bolted. Pyrrhus reached Athens where he entered the city and made his way up the acropolis. After his visit, he told the Athenians that “he was well pleased with the confidence and goodwill to which they had shown him, but in future, if they were wise, they would not admit any of the kings into their city nor open their gates to him” (Plutarch, Pyrrhus, XII). This line seems to suggest a policy of Pyrrhus on turning Attica into a buffer zone. Meanwhile Demetrius, after giving up Athens, sued for peace to Pyrrhus. The latter accepted the peace on the conditions that Thessaly was given to him along with other such cities as Corinth. Gaining Thessaly meant that Pyrrhus could secure his Macedonian possession on the southern frontier and even planning a continuous borderline that runs from northern Aetolia west into southern Thessaly east. Also, the Epirot could rely on the powerful Thessalian cavalry to support the flanks of his army (and use its unique ability to assault in diamond-shape formation).

Yet, the movement south of Pyrrhus seems strategically problematic. It opened Lysimachus the way to gain possession of the whole of Macedon and dispose of Pyrrhus’ authority in favor of his own.

The 285-282 period is full of rapidly changing and radical events in the diadochi theatre of war. In 285, Demetrius perished in battle against Seleucus and his holdings were inherited by Antigonus II Gonatas (“knock-knees”) (ruled 283-239). Lysimachus also murdered Antipater to become the most powerful commander in Europe. He could now conquer Pyrrhus’ Macedonian possessions. To counteract the undisputed Lysimachus, Pyrrhus signed an agreement with Antigonus Gonatas as reported by Phoenicides in his comedy “Aulitrides”. The terms sanctioned Pyrrhus’ possession over Thessaly and lower Macedon and Antigonus’ authority over Demetrias (modern Aivaliotika), Piraeus, and other Greek conquests.

In 283, Lysimachus with his large forces overran Pyrrhus’ portion of Macedon. The Epirot retreated first to Edessa. The forces of the enemy were far more powerful for Pyrrhus to confront them in an open battle. It seems that Pyrrhus initially began preparing a defensive position around Edessa where he hoped for a more effective confrontation with Lysimachus. In Edessa, Pyrrhus waited for reinforcements from Epirus and from help from Antigonus Gonatas. Meanwhile, Lysimachus encroached on his position. No reinforcement appeared to help Pyrrhus and thus he was forced to give up the resistance and with it, the Macedonian throne. Plutarch tells us how Lysimachus, through deceit, persuaded Pyrrhus’ soldier to desert him as the Epirot had once done with Demetrius forces. In reality, other scholars suggest that Lysimachus’ forces were so much larger than it became pointless to fight. Pyrrhus, with his loyal contingents, retreated in Epirus leaving Lysimachus the entire possession of Macedon.

The throne of Macedon turned bitter for Lysimachus. In 282, the latter was eventually assaulted by Seleucus I Nicator (“victor”) (ruled 311-281) whose forces defeated and killed him at the battle of Corupedium. Seleucus himself was murdered shortly after by Ptolemy Keraunos “the Thunderbolt”. Ptolemy was proclaimed king of Macedon (ruled 282-278).

The Eagle Has Landed

The removal of many rivals from the scene offered new opportunities for Pyrrhus in the east. Yet, it was around this time where first embassies from the Hellenic city of Taras or Tarentum came to him and ask for his assistance in the war against the Romans. Tarentum sent messages of assistance to Pyrrhus since 283. The city was an important and prosperous Greek colony in Italian heel, established centuries ago by the Spartans. It had a population of about 200,000 people mainly dealing with trade and commerce. The city also had a long history of quarreling with the Romans who had threatened their sphere of influence by continuously pushing south.

The Epirot was in dilemma between campaigning east or cross the sea and fight against the Romans. In 282, the Tarentines with their fleets helped Pyrrhus regain the island of Corcyra as part of the continuing discussions on an alliance.

The Italian soil offered new opportunities for the Epirot who could pursue a policy similar to that of Alexander the Great against Persia. However, we are also told of the obsession Pyrrhus had towards Carthage and a north African campaign. When considering the precedent of Alexander’s Persian campaign, Pyrrhus imperial ambitions towards the west seem sound but one wonders how feasible. With the diadochi blooming like mushrooms after the rain, Pyrrhus must have felt compelled to fight into a brand new front.

Cineas, the advisor of Pyrrhus, was skeptical about a campaign in Italy. He engages in discussion with Pyrrhus on this matter. Acting as Socrates does in the Platonic “Dialogues”, Cineas repeatedly asks Pyrrhus on his next campaign. Pyrrhus tells how he would first defeat and subdue the Romans. When asked about what would he do after he had defeated the Romans Pyrrhus answered: “Sicily is near and stretches out her hands to us, an island abounding in wealth and men, and very easy to conquer, for there is nothing there, Kineas, but faction, anarchy in her cities and excitable demagogues…and we will use this as a preliminary to great enterprises. For who could keep us away from Libya or Carthage…?” Cineas continued to ask Pyrrhus about his planned conquest until the king eventually ran out of plans and said: “We shall be much at ease, and we’ll drink bumpers…”. Cineas having brought Pyrrhus to this point rightly said: “Then what stands in our way now if we want to drink bumpers and while away the time with one another? Surely this privilege is ours already, and we have at hand, without taking any trouble, those things to which we hope to attain by bloodshed and great toils and perils, after doing much harm to others and suffering much ourselves” (Plutarch, XIV).

Cineas proved his point to Pyrrhus that no matter how many conquests he made, those conquests would not bring him happiness. Although Pyrrhus accepts Cineas’ argument, he continues with the plan of invading Italy.

Pyrrhus accepted the proposal of the Tarentines. Some sources tend to make that as a decision made in haste. In reality, Pyrrhus took considerable time to make that decision. Macedonian kingdom offered even greater opportunities for him. However, its throne was now held by Ptolemy, son of that Ptolemy who had helped him regain the throne in Epirus. Thus, he may have been hesitant to the breaking of a potential alliance with Ptolemy although that did not prevent him from directly pressuring him and the other successors.

Accordingly, Pyrrhus officially demanded military and financial support from Ptolemy Keraunos, Antigonus II Gonatas, and Antiochus I Soter (“the savior”) (ruled 281 to 261). These successors were more than happy to send Pyrrhus on his way and responded with considerable help. According to Justin, Antiochus provided Pyrrhus with financial aid, while Antigonus Gotanas loaned him 30 ships for sea transport. Ptolemy provided the biggest military aid: 5,000 Macedonian phalangites, 4,000 cavalry men including Thessalian riders, and 50 Indian elephants. The elephants’ prior owner seems to have been Seleucus I Nicator who had seized them from Chandragupta Manya (king of Maurya Empire from 321 to 297 B.C.E.) in 305.

The acquisition of these resources and the prompt response of his allies is in itself enough to conclude that Pyrrhus was a force the others Diadochi feared. Pyrrhus must have been aware of his strong position and may have even subtly threatened his helpers that in case they did not come to his aid he would turn his forces against them and not against the Romans. In that sense, the Molossian achieved a spectacular diplomatic victory on the verge of his Italian campaign.

We have little information on Pyrrhus’ generals, commanders, or companions. Up until the crossing in Italy, Plutarch had mentioned only a certain Polysperchon whom Pyrrhus at a drinking-party years ago described as being “a good general”. As for his high command during the Italian campaign, sources tell that Pyrrhus took with him his younger son s Alexander and Helenus.

He would use them and his other general and advisor Milo to command the allied regions in his absence. His oldest son Ptolemy Pyrrhus left in charge of the kingdom. Other otherwise unattested generals and companions were Megacles who fell at the battle of Heraclea, Leonnatus from Macedonia, Euegorus son of Theodorus, Balacrus son of Nicander, and Deinarchus son of Nicias.

The most prominent of Pyrrhus’ advisors or friends was certainly Cineas from Thessaly. He was distinguished for his diplomatic skills and had been a student of the famous Demosthenes. Cineas also wrote an epitome of the tactical treatise of Aeneas Tacticus of Stymphalus and a sort of history presumably dealing with Pyrrhus, Epirus, and Thessaly.

In 281, Pyrrhus sent in advance a force of 3,000 men along with the “silver-tong” Cineas in Tarentum. Pyrrhus himself followed about one year later with the main army: 20,000 infantrymen, 3,000 cavalries, 2,000 archers, 500 hundred Rhodian slingers, and 20 elephants.

We do not know certainly why Pyrrhus took only 20 elephants in Italy when Ptolemy Keraunos had provided him with 50 of them. It seems that either the other 30 elephants were not trained for combat or that he lost them during a storm at sea while crossing them into Italy. The sources seem to support more the later option; however, the former option should not be ignored.

Elephants were a valuable possession and must have been distributed on board of the strongest ships. Antigonus Gonatas provided Pyrrhus with transport ships that the Epirot somehow adopted to carry his elephants. The fleet was hit by a serious storm when it approached the coast of Italy. The storm forced Pyrrhus to jump out of his flagship with his men and swim into the nearby shore.

Despite the storm at sea, most of Pyrrhus’ forces landed safely into Messapia. There, he was greeted with high regard from the Messapians who were aware of his deeds and his lineage. Pyrrhus had already accomplished a major achievement: he had become the first person to invade a country with elephants through the sea. Then, the full force marched into Tarentum where they were welcomed by Cineas.

When in Tarentum, Pyrrhus noticed how the Tarentines continued with their usual works as if they were not in war. Thus, he established the “martial law” in the city and initiated the recruitment of eligible Tarentine men into his force. When recruiting soldiers, Pyrrhus said to the Tarentine: “You pick out the big men! I’ll make them brave” (Frontinus, IV.I.III). This clearly reveals his strategy, typical of Hellenistic kings, of using a mixed force of Epirots, Allies, and mercenaries to fight the Romans. The eventual victories achieved with a mixed force prove the high competence of Pyrrhus as general and commander.

To rally up the Tarentine and the allies, Pyrrhus initiated clever propaganda that justified his presence there. Among other instruments, Pyrrhus issued new coins for the city proclaiming his lineage from Achilles, Alexander the Great of Macedon, and Alexander the Molossian. Cineas must have also helped a great deal in convincing the Tarentines of the king’s good intentions.

Pyrrhus Ad Portas

Upon hearing of Pyrrhus arrival, the Roman consul Publius Valerius Laevinus mustered a large army and moved it against the Epirot king at speed. Laevinus wanted to bring Pyrrhus into a pitched fight before the latter could be supplied by allied reinforcements. Also, by moving first, the consul moved the theatre of war far away from Rome, into enemy territory.

Accordingly, Laevinus led his force through Lucania, plundering as he advanced. Pyrrhus took his forces and marched out of Tarentum to at least block the enemy advancement. The king had an army inferior in numbers (no more than 30,000 men). Apart from a continent from Tarentum, Pyrrhus lacked military support from other allies across southern Italy. These allies were apparently waiting for the turnout of the battle of Pyrrhus against the Romans before declaring a formal allegiance.

Epirot forces arrived in the plain between Pandosia (modern Santa Maria d’Anglona, Tursi) and Heraclea (modern Policoro), southwest of Metapontum (modern Metaponto, Bernalda). Here Pyrrhus smartly chooses a favorable place to set his camp with river Siris (modern river Sinnis) in his front. Then, he placed a contingent of about 3,000 missile men to guard his side of the riverbank. Himself, with the main troops, stood on the camp to wait for allied’ military support. Pyrrhus had thus blocked the enemy’s path and had no reason to initiate a fight.

The Roman army had also arrived at the site where they had to position on the opposite side of the river. Not long after, determined to engage the Epirot, the Romans took the initiative. Abruptly, the whole Roman army began crossing the river, the infantry using fords and the cavalry on the flanks charging through the water. The guarding contingent at the riverbank was caught by surprise yet tried to succumb to the Romans as they crossed. Soon their flanks were undermined by the Roman cavalry so they hastily began their retreat towards the main camp.

On the news of the Roman charge, Pyrrhus mobilized his army and moved them all into the river crossing where they confronted the enemy. The phalanx at the center slowly pushed back the legionaries. Meanwhile, at the flanks, the cavalries fought for gaining superiority on the flanks. Pyrrhus himself rode alongside his companions and aided them personally in defeating the enemy. His involvement almost cost him his life when a certain Frentanian named Oplax, commander of a contingent of cavalry, threw his spear at Pyrrhus. The shot missed Pyrrhus but slew his horse and that of Leonnatus, his Macedonian companion. As his horse fell, Pyrrhus was saved from hitting the ground by his companions. After the incident, the king switched his cloak, armor, and helmet with Megacles while himself retreated unnoticed into the safety of the back lines.

The things turned bitter for Pyrrhic horsemen at the place Pyrrhus had just left. Megacles, who many perceived to be the king, was soon overwhelmed by the enemies until he was killed by a certain Dexous. The latter, thinking he had killed the king[1], grabbed the victim’s cloak and helmet and, holding them high displayed them as he rode in front of Laevinus. The Romans were somewhat encouraged by this while the Pyrrhic soldiers got confused. When Pyrrhus realized the problem, he rode along his line with his face bare to let his soldier know that he was alive and encourage them to decimate the enemy. (Pyrrhus, XVII).

To regain domination on the flanks, Pyrrhus released the elephants that were until now kept in reserve. This would confront the Roman soldiers with creatures they had never confronted before. This alone would be enough to put them in disorder.

According to Dion Cassius: “Pyrrhus raised the signal for the elephants. Then, indeed, at the sight of the animals, which was out of all common experience, at their frightful trumpeting, and also at the clatter of arms which their riders made, seated in the towers, both the Roman themselves were panic-stricken and their horses became frenzied and bolted, either shaking off their riders or bearing them away. Disheartened at this, the Roman army turned to flight, and in the rout the soldiers were slain by the men in the towers on the elephants’ back, and others by the beasts themselves, which destroyed many with their trunks and tusks (or teeth) and crushed and trampled underfoot as many more. The [Thessalian] cavalry, following after, slew many and not one, indeed, would have been left, had not an elephant been wounded, and not only gone to struggling itself as a result of the wound, but also by its trumpeting thrown the rest into confusion. This restrained Pyrrhus from pursuit”.

The victory brought valuable political results to Pyrrhus. The whole of southern Italy, including the Greek colonies of Croton (modern Crotone) and Locri and the non-Greek populations of the Samnites, Lucanians, and Brutti joined his cause and offered military assistance. These reinforcements not only covered the casualties suffered in Heraclea but brought the total number of soldiers under Pyrrhus command to 40,000.

The Epirot celebrated the victory with a sacrifice (ex-voto) for Dodona. Then, with full strength, he marched north as far as Praeneste (modern Palestrina) only some 37.5 kilometers from Rome. Here he tried to turn the populations and cities of Campania against Rome. However, the nature of the Roman institution of friendship made the diplomatic venture and military pressure of Pyrrhus in Campania unsuccessful. The Epirot must have been surprised by the unshaken trust of the Roman allies and the determined stance of their cities. Back east, cities would commonly and banally open their gates to any powerful approaching army. In Italy, allied cities would not open the gates to an enemy, and they did not do so to Pyrrhus.

Nevertheless, the Pyrrhus opening campaign had been successful. The Roman had been defeated in open battle and driven out of southern Italy, while the southern Italic populations joined Pyrrhus’ side. After completing the Campanian circuit, Pyrrhus with his main army retreated in Tarentum to winter.

A Roman “Demosthenes”

In the meantime, two sets of post-battle negotiations followed. The first negotiation for the exchange of prisoners was concluded successfully: both Pyrrhus and the Romans released prisoners without ransom. The exchange of prisoners opened formal peace negotiations. The Roman Senate commissioned Gaius Fabricius Luscinus Monocularis to conclude a peace with Pyrrhus. The later may have even used the son and successor of his ally Ptolemy II Philadelphus (ruled 282-246 B.C.E) to improve his bargaining power. According to Justin, the Senate sent an envoy as far as Egypt to meet with Ptolemy and have him back up the treaty with Pyrrhus.

At about this time, the Carthaginians appear on the scene, clearly reacting to a potential alliance between Pyrrhus and Rome. A peaceful resolution between Pyrrhus and Rome would then allow either of the sides to intervene with full strength in Sicily and threaten Carthaginian possession there. To prevent this, the Carthaginians needed an alliance with at least one of the sides that fought in Heraclea. First, the Carthaginians approached the Romans. A fleet of 120 under the command of Mago (grandfather of Hannibal) appeared in Ostia near Rome. He offered before the Senate the support of the Carthaginian fleet in the war against Pyrrhus. The Senate initially turned down the offer, as their commissioner had concluded a peace with Pyrrhus. Following the Senate’s initial refusal, Mago went to Pyrrhus rather quickly and apparently made him a similar offer: naval assistance from the Carthaginians if he continued the war against the Romans in mainland Italy. Pyrrhus, being in process of securing peace with Romans, refused the Carthaginian help.

Eventually, sometime during the winter of 280, Luscinus and Pyrrhus agreed on peace. The terms seem to have been favorable to the Molossian. Cineas was sent in Rome from Pyrrhus to present the peace agreed to a Senate seemingly inclined to ratify it. Ancient sources tell us that just before the Senators were going to ratify the peace with Pyrrhus, Appius Claudius Caecus, was escorted in the Senate room. Appius Claudius was blind and old, but he had influence over the Senators, some of which he had promoted in that office himself. He had been consul in 307 and then again in 296. He had also been censor in 312, a duty during which he had constructed both the Via Appia and the first Roman aqueduct, the Aqua Appia. Clearly, Appius Claudius was the most influential Roman politician of his time. In the speech held before the Senate, he declared against any peace with Pyrrhus as long as he later maintained his forces in the peninsula.

Appius Claudius’ speech turned the Senators against a peace deal with Pyrrhus. However, that speech alone cannot be credited for such a swift change in politics. Rather, the senators knew that they could go back to the Carthaginian offers and with their help fight Pyrrhus on two fronts. And so they did. After the Senate voted against peace with Pyrrhus, the Romans reinitiated negotiations on an alliance with Carthaginians.

As for Pyrrhus, his limited understanding of Roman politics suggest that he did not expect such a behavior from the Romans. As far as he was concerned he had already made peace with them as he must have perceived Luscinus as their highest authority on the matter. Pyrrhus had sent Cineas on Rome with precious gifts apparently for celebratory purposes rather than purely bribing purposes as many believe. It was only after the demise of the treaty that Cineas, present in Rome, understood the nature of Roman politics. He clearly understood how Appius Claudius had played the role of Demosthenes, his former teacher, among the Romans.

Cineas returned to Pyrrhus with the news of the broken peace. It was here that one of them presumably compared the Romans to the Lernaean Hydra referring to the speed at which the Romans could gather new armies after each defeat.

Far from a “Pyrrhic victory”

Thus, Pyrrhus had to fight another fight against the Romans. By spring, Pyrrhus advanced with his force in Apulia, determined to remove Roman colonies there, especially that of Venusia (modern Venosa), established in 291, as well as Luceria (modern Lucera). Those towns belonged to a chain of Roman settlements that surrounded the Samnites and that Pyrrhus tried to break. By breaking Roman colonies here, Pyrrhus was attempting to reach the Samnites, turn their territory into a safe domain, and use their population as a mercenary force. Many places across Apulia surrendered without a fight. Others, Pyrrhus captured with minimal efforts.

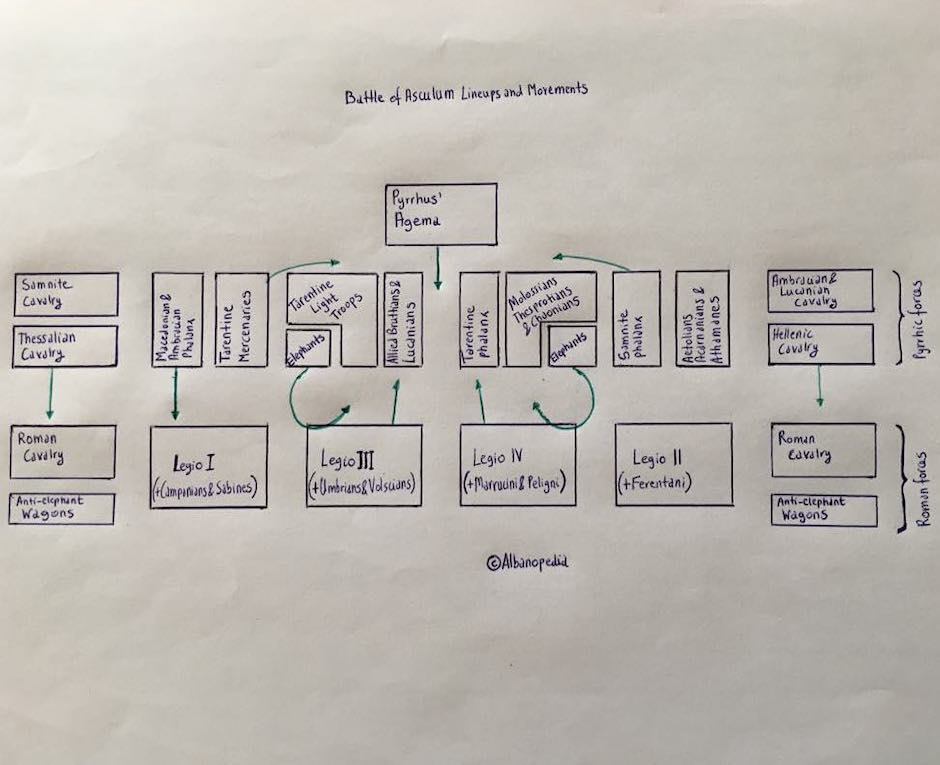

The Romans appeared in Apulia with an army even greater than the previous one. The two forces meet near Asculum (modern Ascoli Piceno) at a marshy terrain near river Carapelle. The Epirot kept his forces away from the river in order not to lose the superiority of his phalanx in the river swamps. The size of each army varies from 40,000 to 80,000 men. However, both the forces were about equal in size.

For this battle at Asculum, the Romans had crafted a wide range of anti-elephant weapons. About 300 hundred wagons were exclusively deployed by them on the wings. These wagons had caltrops against elephants’ feet, swinging blades to cut their trucks, and fiery-grappling hooks to hit and burn them.

At first, Pyrrhus came with his elephants at his wings, as in Heraclea, but when noticing the wagons targeted at them he changed his deployment. Thus, he moved the elephants on the front to act as “tanks” where they could also stay away from the anti-elephant wagons of the enemy. Pyrrhus was using the elephants as no one had before used. He had mounted towers with archers on their backs, essentially turning them into mobile artillery platforms, while still serving as heavy cavalry.

Pyrrhus, keeping a relatively weak center, moved against the enemy with powerful wings. The elephant initiated the fight and stumped right through the legions at the center, crushing their lines and routing them. At the same time, the king ordered his archers and slingers to assault and kill the men operating the anti-elephant wagons. The pressing on the flanks continued by a superior Thessalian cavalry able to dominate over a stationary Roman and Latin cavalry. The elephants he kept at constant move breaking as many Roman lines as possible.

Ancient sources report a push from the legions in the center, namely from the Legio III and Legio IV. However, this seems to have been a calculated move from Pyrrhus. As these legions pushed forward by routing some of Pyrrhus less skilled soldiers, the Epirot king squeezed them by blocking their advancement himself with his two thousand units of Companions (called royal agema) while still pressing from the superior flanks. The Roman and Latin cavalry had by now driven out of the battle. The two legions, now trapped by the phalanx and cavalry charges suffered many losses before forced into retreat.

Roman sources and literary tradition have tried to manipulate the outcome of this battle. Only in recent years have scholars understood the unrealistic reports of the Roman sources and acknowledge Pyrrhus superiority in both commands and in soldiers. Plutarch follows Roman tradition although at least awards Pyrrhus the victory. According to the author, Pyrrhus when congratulated by one of his friends on the victory presumably responded: “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined”. This phrase, which Pyrrhus may have never actually said, gave rise to the term “Pyrrhic victory” to refer to a victory achieved at a great cost. However, Pyrrhus’ victory was not a Pyrrhic victory. The Romans lost at least about 6,000 men while Pyrrhus lost no more than 3500 men (even that at an inflated rate).

Although victorious, Romans proved a persistent foe. Pyrrhus himself, according to Dionysius, was wounded in the shoulder by a javelin. This is no wonder when considering the habit of Pyrrhus to involve personally in the fightings. Another damage was caused by Daunians who, unable to join consuls at the fight, plundered Pyrrhus’ personal baggage and his camp.

The Carthaginian Front in Sicily

Following the defeat at Ausculum, Rome ratified the alliance with Carthage in the summer of 279. After securing the alliance with Rome, Carthaginians opened a new front against Pyrrhus by besieging Syracuse. A land force of 50,000 and a fleet of 100 ships kept the whole colony under siege while constantly ravaging their lands. Sieged Syracusans led by Sostratus who controlled the city and Thoenon who controlled Ortygia, sent embassies in Italy to ask for the assistance of Pyrrhus. The latter felt compelled to act and promptly assembled 60 warships and other transport vessels to carry 10,000 of his infantry and about 500 cavalries (apparently Agema and Thessalian contingent) as well as 19 elephants into Sicily. He left his remaining forces in Italy, some as garrisons at Tarentum to keep them in check, and others as defenders of Locris.

Pyrrhus’ strategy had turned into a grand strategy of enormous proportions. It was still, a sound strategy. Years ago, Agathocles had almost conquered Carthage by taking the war into Northern Africa, the same strategy was later successfully used by Scipio. The Epirot was apparently following the same policy. He hoped to expel the Carthaginians from the entire Sicily and potentially return the Libyan Sea as a new frontier and barrier between Sicily and Carthage. With Sicily and his back secured, he could then refocus on the persisting Romans at an added strength or sent the war into North Africa.

The crossing into Sicily was a challenge on its own. Pyrrhus had to sail through an alternative route as the Straits of Messina were controlled by the Mamertines, recently allied with the Puns, and the bandits at Rhegium (modern Reggio di Calabria). Also, the Carthaginian navy patrolled the straits to prevent Pyrrhus’ armada from crossing into Sicily.

Pyrrhus expected the danger of crossing through the Straits and forced his armada into a different course. The Epirot king set sail from Tarentum and arrived in 10 days in the secured base of Locri (modern Reggio di Calabria). Then, the Epirot continued his sail to Catana/Katane (Catania). There, he disembarked his the infantry who continued their march on foot towards Syracuse. The ships continued their sail in parallel with infantry advance, protecting them from naval threats.

Pyrrhus’ fleet dodged the enemy patrollers by sailing below the heel of Italy, from Locri into Tauromenium (modern Taormina), just south of Messana (modern Messina). The dynast of Tauromenium, Tyndarion pledged his allegiance to Pyrrhus and supplied him with a continent of his soldiers. The fleet continued its sail south and arrived in Catana/Katane (modern Catania). There, Pyrrhus landed the infantry with instructions to march safely on foot towards Syracuse. Meanwhile, the ships continued their sail in parallel with infantry advance, protecting them from potential naval threats.

When both Pyrrhic infantry and navy appeared in Syracuse/Syracusae (modern Siracusa), the Carthaginian fleet and land forces, already there, were caught by surprise and stood at an inferior position. The Puns had transferred some forty thousand troops farther north, into the straits to expect for a Pyrrhic landing there. Only about 10,000 Carthaginian land forces had remained in Syracuse to keep it under siege. Also, some 20 (out of a 100 they had stationed there) had been sent away for supplies which reduced the overall size of their navy.

By avoiding the Straits of Messana, Pyrrhus had devalued the 40,000 strong Puns that were stationed near the straits and had Syracuse on a silver platter. The Carthaginian land forces went into disarray while the whole of their fleet sailed away without resistance. Pyrrhus arms and ships took possession of both Ortygia and Syracuse.

In Syracuse, Pyrrhus successfully negotiated peace between Thoenon and Sostratus allowing the Syracusans to regain their rights of trade and communication. This also unified the forces of the colony against the common enemy. Meanwhile, he took over the defense and siege weaponry of the city. Moreover, Syracusans provided him with 120 decked ships, 20 without decks, and a massive royal ship with nine sets of roars. This swelled the size of the Pyrrhic fleet into more than 200 ships.

Envoys from Leontini (Lentini) sent by their ruler Heracleides, appeared in Syracuse and offered the control of their city to Pyrrhus. Leontini also provided him with a force of 4,000 infantry and 500 cavalries.

After securing the control of Syracuse, Pyrrhus moved with his forces against Acragas (Agrigento). He took with him Sosistratus as his general and restored him as ruler of Acragas in return for this city’s alliance. The Carthaginian garrison had been expelled in advance by pro-Pyrrhic citizens in the city. At Acragas, Pyrrhus received additional 8,000-foot soldiers and 800 cavalrymen. Other cities under Sostratus’ dominion also pledged their allegiance to Pyrrhus. The natives from the town of Enna/Henna had also expelled the Carthaginian garrison and declared their support for the king. Soon after gaining the support of Enna, Pyrrhus captured the town of Azones/Assorus (modern Assora), thus securing complete control over central Sicily.

After receiving additional support from all allies across Sicily, the infantry force of Pyrrhus tripled since he crossed into Sicily: now reaching 30,000 infantry; the cavalry force had also increased to 2500 horsemen.

With an army of this size and the fleet, Pyrrhus advanced against the Carthaginian possessions. He at once relieved the Greek city of Heracleia/Heraclea Minoa (Cattolica Eraclea), up until then garrisoned by Carthage. Then, he received voluntarily the Greek cities of Salinas/Selinus (modern Marinella di Selinunte, Castelvetrano), Halicyae (modern Salemi), and the native settlement of Segesta (modern Calatafimi-Segesta).

Pyrrhic advance forced the uncoordinated Carthaginians into constant retreat. The Puns avoided Pyrrhic force and planned a defensive strategy based on three of their strongest fortresses: Panhormus (Palermo), Eryx (modern Erice), and Lilybaeum (Capo Boeo, Marsala).

Eryx and Lilybaeum

With a siege train from Syracuse, Pyrrhus assaulted the walled cities of Panhormus and Eryx. The Molossian invested heavily in conquering Eryx. The Carthaginian there made a brave resistance forcing Pyrrhus into a siege position for a considerable time. Diodorus and Plutarch tell how Pyrrhus led personally the first wave of ladder assault up the wall of Eryx to encourage his troops to follow suit. On reaching the top, again in a fashion adapt for Homeric poems, Pyrrhus killed all the enemies rushing against him and so seized the place. After a massive army assaults with ladders and missiles, the town soon fell. The remaining Carthaginian garrisons were captured and executed. After the massacre at Eryx, Pyrrhic troops captured Panhormus without a struggle.

Lilybaeum remained Carthaginians’ only stronghold in Sicily. The combined Epirot and Sicilian forces encircled it and put it under siege. Lilybaeum stood at the tip of a narrow isthmus, over rocky terrain, making it most difficult to conquer. It was clear that the siege would be a long one. At this point, the Carthaginians encouraged the Mamertines to harass Pyrrhus’ allies. Pyrrhus responded by dealing with the Mamertines himself. After leaving a part of his forces to maintain the siege and blockading Lilybaeum’s port, he advanced against the Mamertines. Pyrrhus defeated the Campanian enemy despite their bold resistance.

Meanwhile, the Carthaginians used the time well and erected serious fortifications to improve the defenses of Lilybaeum. They walled the narrow length of the isthmus and raised multiple towers on its sides. Yet, they also entered into peace negotiations with Pyrrhus asking him to spare their only remaining stronghold in Sicily and offered him a large sum of money in return. Pyrrhus refused the deal and continued the siege. A series of assaults were made against the fortifications but the Carthaginians with concentrated force repelled all of them. Pyrrhus even built new siege equipment to pierce through the walled fortifications but was again repelled. After two months of failed attempts, Pyrrhus raised the siege.

The decision of Pyrrhus to relieve the siege is regarded as a major mistake. Some scholars believe that he should have spent more time in besieging the city until its defendants were forced to surrenders. However, two months of siege was not a short time and there was no indication that the Carthaginians would surrender. Lilybaeum could prove to be another “Rhodes”. Also, Pyrrhus still kept the pressure on Lilybaeum even after releasing the siege of the isthmus by keeping its port blockaded.

However, the ongoing refusal of the Carthaginian peace offer seems a diplomatic fiasco from Pyrrhus. If Pyrrhus would have accepted the Carthaginian alliance he could use their splendid naval prowess against Rome. As Jonathan Recalding (2010) rightly puts it: “Pyrrhus’ rash decision to ignore their (Carthaginian) help doomed his campaign and was a diplomatic catastrophe”. The decision to refuse Carthaginian help and relieve the siege of Lilybaeum is attributed to Pyrrhus’ rash tempter. This theory cannot be ruled out but contradicts other smart diplomatic moves made previously from Pyrrhus. The topic deserves still specific treatment including other approaches.

After his victories over Mamertines and Carthaginians, Pyrrhus began designing a united Sicilian kingdom with him or his son Alexander as a king. In the process of achieving this design, the Epirot made authoritative decisions and aggressive interventions in Sicilian affairs. This caused him to lose much popularity across the island and eventually forced Pyrrhus to back away. On leaving Sicily, Pyrrhus famously remarked: “…what a wrestling ground for Carthaginians and Romans we are leaving behind us!” (Plutarch, XXIII), accurately predicting the Punic Wars.

On his way back to mainland Italy, the Sicilian fleet carrying Pyrrhic forces across the straits was assaulted by Carthaginian ships. This caused the loss of some of the force and the ships and made the landing near Rhegium most difficult. Then again, near Rhegium, the landing forces were assaulted by Campanian bandits causing casualties among the rear, the loss of two elephants, and a wound on the head to Pyrrhus. The latter was able with difficulties to repel the Campanian assault and only then travel back safely into Tarentum.

Return in Italy and Beneventum

Despite the difficult journey, Pyrrhus returned to Tarentum in the spring of 275 (or fall of 276) with a solid force of 20,000-foot soldiers and 3,000 cavalries. He then added to this force the other troops he had stationed at Tarentum along with Tarentine reinforcements.

It is commonly thought that the Romans had exploited Pyrrhus’ absence to regain much territory. In reality, only the Samnites had suffered from Roman operations. Yet, the Republic had not achieved anything decisive during the truce they enjoyed from Pyrrhus’ absence.

For the campaigning season of 275, the Romans prepared two consular armies to face Pyrrhus, one under Manius Curius Dentatus and the other under Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Caudinus.

Pyrrhus split his army into two parts. He sent a detachment to face the consular army of Lentulus in Lucania and stall him there. Meanwhile, with his main force of about 30,000 soldiers, Pyrrhus marched against the other consul Manius Curius that had encamped near the town of Beneventum. With this move, the king had successfully avoided Roman armies from joining but had yet two defeats Curius’ well-prepared force of about 25,000 men.

Pyrrhus tried a forced night march to catch the Roman army by surprise. This move proved difficult in a terrain unknown to him. When a portion of his army approached the Roman right flank, the Romans were already up and could notice their enemy at a distance. The Romans were certainly surprised by the enemy’s appearance but the soldiers were already on guard. Pyrrhus now faced a fresher enemy with his now tired force.

When the forces clashed, the Romans pushed against the tired Pyrrhic lines. The king released the elephants on the flanks but the Romans had prepared a “flaming pig” strategy against these animals. By literally setting pigs on fire and throwing them at the elephants the Romans were able to force them to flight. The elephants even went wild and turned against their own lines. Outmaneuvered in flanks and pushed on the front, Pyrrhus signaled the retreat.

Return into Epirus and Macedon

Pyrrhus battle at Beneventum was a decisive loss but not a disaster as the Roman literal tradition claims. The retreat was orderly and most of the troops were brought back safe into Tarentum. What Pyrrhus lacked were soldiers and money.

While in Tarentum, Pyrrhus asked for the help of Antigonus Gonatas and Antiochus I if he was to keep the fight in Italy. He may have even threatened Antigonus with turning his arms against him if he did not respond with support. Antigonus, now secure in his throne did not respond to Pyrrhus’ demands and so the Epirot king decided to return to Epirus. Before crossing into his domain, he left his own garrison in Tarentum under the command of his son Helenus and Milo. Then, he set sail for Epirus with 8,000 infantry and 500 cavalries.

Upon returning to Epirus, Pyrrhus began preparing a campaign against Macedon. Antigonus’ refusal to help him in Italy had given the Epirot the pretext to interfere in Macedonian affairs. In 274, he launched the campaign against Macedon. At a narrow gorge along the River Aous (Vjosa), Pyrrhus met the army of Antigonus. Here, many Macedonians defected to Pyrrhus, and the remaining Antigonid forces were crushed by a sturdy Pyrrhus along with their Gallic mercenaries. The elephant garrison of Antigonus was captured without a fight.

After the victory, Pyrrhus took possession of the upper Macedon and Thessaly. Antigonus retreated with a small continent of his horsemen into Thessalonika (modern Thessaloniki) where he tried to regroup his forces. His new force was soon defeated by Pyrrhus’ son Ptolemy forcing Antigonus to escape with only seven of his companions from the entire kingdom.

Rather than pursuing Antigonus, Pyrrhus moved on plans of invading Peloponnesus. In Peloponnesus, Cleonymus had proposed Pyrrhus an alliance against Sparta and its king Areus I (ruled 309-265 B.C.E.) who was away campaigning in Crete. Establishing his rule over Peloponnesus and installing a puppet king into Sparta proved tempting for Pyrrhus. The conquest of Peloponnesus would also allow Pyrrhus to conquer the remaining Antigonid strongholds along with southern Greece.

Sparta and Argos

In 272, he crossed the Gulf of Corinth through sea avoiding the Corinthian isthmus under Antigonid control. Pyrrhus’ army included 25,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and 24 elephants. In Peloponnesus, Pyrrhus was welcomed by delegations from the Athenians, Achaeans, and Messenians who seem to have promised him safe passage along their regions. Heroic victories against the Romans had made Pyrrhus the most renowned general of his time among all Greeks, Macedonians, and other populations of the region.

He soon moved against Megalopolis (modern Megalopoli) and took it by false claims and promises. He soon plundered his way along with the Laconian territory, marched along the western foot of Tagyetus mountains through friendly Messenia, until he reached Sparta from the south. Near the city, Pyrrhus faced a Spartan army of 15,000 men and routed them. The Spartans inside the city, pessimistic about their position, began a discussion on surrender. When the Spartans proposed to send their women away into Crete, Archidamia “came out with a sword in her hand to the senator and upbraided then behalf of the women thinking it meet that they should like after Sparta had perished”.

The Spartans kept their resistance and with the help of the women prepared parallel trenches fronting the enemy camp with anti-elephant wagons on the flanks. The Spartan forces took position behind the trench to make their stance there.

Pyrrhus forces tried to smash through the trench and the enemy but the defendants made a fierce stance. Meanwhile, Pyrrhus’ son Ptolemy at the command of 2,000 Gauls and hand-picked Chaonians tried to outflank the trench by attempting a move against the wagons there. The maneuver caused some confusion among the Spartans there, who began wavering. At this point, prince Acrotatus moved unnoticed with 300 elite Spartan fighters at ambushed Ptolemy at his rear. A great slaughter followed where most of the Ptolemy’s continent was killed.

A major slaughter took place at Pyrrhus’ front position as well. Pressing hard on the enemy caused the demise of many Spartans including distinguished fighters such as Phyllius. After fighting all day, the two sides retreated into their own positions without a verdict.

The next day, a determined Pyrrhus gathered his forces and resumed the fight. Pyrrhic forces tried to fill the trenches so they could form a level passage for their forces. The Spartans still assaulted levelers and made a bold stance. Many fell again from both sides near the trenches. Pyrrhus himself tried to break into the wagons until a Cretan javelin killed his horse and threw the king into the slippery ground. The continuous fight allowed reinforcements to reach Sparta, namely forces from Antigonus led by Ameinias the Phocian and Areus with 2,000 men who had promptly returned from Crete. The reinforced city forces Pyrrhus and his forces to leave the site.

Pyrrhus thought to compensate for Sparta by assaulting the city of Argos. In this city, two politicians called Aristippus and Aristeas were feuding against one another. Aristippus supported Antigonus so Pyrrhus naturally moved in favor of Aristeas. With continents of his force, Gallic mercenaries and the elephants Pyrrhus launched a night assault into the city. Aristeas had opened the gates to allow Pyrrhus to capture the city unmolested. However, because of their narrowness, Pyrrhus had difficulty with leading elephants along with the gates. The noise of the animals struggling to get through alarmed the Argives who began preparing for the enemy.

When the contingent crossed the gates and occupied the marketplace, the Argives descended against them and confusion took place. Because of darkness, there was no organized fighting and no command was effective.

In the morning, reinforcement arrived in Argos to relieve the city. Antigonus appears near Argos and sent in the city his son along with a considerable relief force. This force was soon joined by Areus with a combined force of 1,000 Spartans and Cretans. When Pyrrhus became aware of his position he ordered his force into retreat in an attempt to return his force outside the walls. He also sent a messenger to his son Helenus who was waiting outside with the main force with instructions to destroy the gates so that his forces can quickly cross them. The messenger, in the midst of surrounding urban confusion, misunderstood the instructions and messaged Helenus to move into the city. Accordingly, Helenus moved into the gates where they bumped into the forces of Pyrrhus who were actually trying to go outside the gates. Here the Argives rushed against Pyrrhus and his companions who were trying to make way into the mess at the gates.

“…Pyrrhus, seeing the stormy sea that surged about him, took off the coronal with which his helmet was distinguished, and gave it to one of his companions; then, relying on his horse, he plunged in among the enemy who were pursuing him. Here he was wounded by a spear which pierced his breastplate-nor a mortal, nor even a severe wound-and turned upon the man who had struck him, who was an Argive, not of illustrious birth, but the son of a poor old woman. His mother, like the rest of the women, was at this moment watching the battle from the house-top, and when she saw that her son was engaged in conflict with Pyrrhus, she was filled with distress in view of the danger to him, and lifting up a tile with both her hands threw it at Pyrrhus. It fell upon his head below his helmet and crushed the vertebrae at the base of his neck, so that his sight was barre and his hands dropped the reins. Then he sank down from his horse..a certain Zopyrus, who was serving under Antigonus, and two or three others, ran up to him, saw who he was, and dragged him into a door-way just as he was beginning to recover from the blow. And when Zopyrus drew an Illyrian short-sword with which to cut off his head, Pyrrhus gave him a terrible look, so that Zopyrus was frightened; his hands trembled, and yet he essayed the deed…” (Plutarch, XIV). So fell one of the greatest generals of his time.

Legacy of Pyrrhus

Pyrrhus believed that a king should focus most on military matters and delegate other duties to others. He had a habit of engaging himself in the fights thus risking his life in combat multiple times. The focus on military affairs made him a splendid military innovator. He made excellent use of the combined arms strategy with a strong focus on heavy cavalry and elephants. He was the first to equip his cavalry with javelins thus increasing their hitting power (known thereafter as the Tarentine cavalry). Pyrrhus also made effective use of local troops to help the phalanx in its mobility and replenish the gaps created when the phalanx engaged the enemy. These light-armed local troops were also known as “thureophoros” with their large oval shields and javelins or swords were later introduced by Pyrrhus into Greek warfare. Pyrrhus was also the first to organize the entire army into a single camp.

Along with military campaigns, Pyrrhus embarked on large construction projects across Epirus which increased the prosperity of his kingdom. Notably, Pyrrhus constructed a large theatre at Dodona that could seat 17,000 thousand people along with a colonnaded precinct there. We even here of a surreal project of Pyrrhus designing the construction of a long bridge across the Ionian strait so that he could invade Italy through the land.

He also founded new cities and, in the fashion of other Hellenistic kings, such as Berenice (modern Kastrosykia), whom he named after his mother in law, and Antigonea (modern Saraqinishtë), named after his first wife. Other constructions included a round wall along his capital Ambracia and the addition of a new also fortified suburb in the capital called the “Pyrrhaeum”, the acropolis at Passaron, and many other sites.

Along with improvements in urbanization he sought to encourage civic activities by organizing the festival of Naia, an athletic competition held every four years.

Pyrrhus campaign in Italy and Sicily was not a total fiasco. As long as he was alive, Tarentum was kept firmly under his control. The city would be conquered by the Romans only in 272 B.C.E.

He apparently planned to return to Italy and face the Romans with renewed forces. In Sicily, Pyrrhus too maintained friendly ties with the city of Syracuse. Before leaving Sicily he married his daughter Nereis with Gelo, son of Hiero I who became tyrant of Syracuse in 275 B.C.E.

“King Pyrrhus of Epirus was, in many ways, one of history’s great rulers; he was virtuous, valorous, strong, tactically competent, and the author of works on military strategy which, while lost to time, were proof enough for the ancient scholars to consider him a formidable military intellect.

He always fought in the front ranks with his men, killing the enemies’ champions personally. There is one famous instance in which he was fighting Mamertines in southern Italy; Pyrrhus was struck in the head and fell to the rear of the battle. One Mamertine stepped forward, asking Pyrrhus to show himself if he was still alive. The king threw off his guards, raced across the field, and brought his fine sword down upon the crown of the man’s head with such force and rage that the warriors was cut in two, and the Mamertines ran away, knowing Pyrrhus was more than a mortal man. Such feats brought his fellow Greeks to consider him a worthy successor to Achilles and Alexander”.

Pyrrhus wrote a “Tactic” discussing, among others, his battles against the Romans. The book had a low circulation at the time and did not survive. A copy of his “Tactic” fell into the hands of a Carthaginian cavalry commander called Hannibal.

Bibliography

Aeliani, Claudii. De Animalium Natura.

Cross, Geoffrey Neale (1932). Epirus, A study in Greek Constitutional Development.

Diodori. Bibliotheca Historica.

Dionis Cassi Cocceiani. Historia Romana.

Dionysi Halicarnassensis. Antiquitatum Romanarum.

Flori, L. Annaei. Epitome.

Frontini, Julii. Stratagematon.

Hughes, Tristan (2017). Who was king Alexander of Molossia? The other Alexander.

Iustini, M. Iuniani. Epitoma. Historiarum Philippicarum.

Pausaniae. Descriptio Graeciae.

Pyrrhus of Epirus and the Roman Republic. Retrieved from: https://erenow.net/ww/warfare-in-the-classical-world-an-illustrated-encyclopedia/8.php?fbclid=IwAR2e3S6PD9w0MUYiNP9ADquEh4wXEOc03UattZz1IVdn7xt4SV-9G4TMeew.

Recaldin, Jonathan (2010). Pyrrhus of Epirus: Statesman or Soldier? An analysis of Pyrrhus’ political and military traits during the Hellenistic Era.

Strabonis. Geographica.

Zonarae, Joannis. Epitomae Historiarum.

Your article fails to mention how the ancient Epirotes and Pyrrhus were Greek by blood. Almost all the major ancient historians clearly state this. And it is recognized by most academic scholars. The mollossian tribes have roots with that date back with Achilles. It’s fine you post an article about one of the greatest Greek leaders of antiquity but at least admit the truth.