Bylis: City of Mosaics

Bylis was an Illyrian city inhabited by the Illyrian tribe of the Bylines. The earliest literary source related to the Bylis region belongs to “Periplus” of Pseudo-Scylax (Scyl. XXVII) compiled around 380 B.C.E. In a passage, the author infers the presence of a joint koinon (league) that involved the tribes of the Bylines and the neighboring tribe of the Amantes. A contemporary inscription (dated 360-340) deposited in the oracle of Dodona supports the presence of such a community involving the tribe of Bylines.

Early History

In a broader sense, the Bylines and their community were constituents of Atintania, a larger Illyrian state. It stretched over the whole lower and mid-valley of the Aoos River. Atintania, previously under Molossian control, regained its independence in 385 when the Illyrian king Bardylis defeated the Molossian army. After gaining freedom from the Molossian, the region experienced fast urban development. Thus, sometime before 350, the Bylines founded the city of Bylis. Many authors suggest that the natives who founded Bylis came from the nearby city of Nicaea (current village of Klos), a settlement inhabited since the second part of the V century.

In 314 the Macedonian ruler Cassander conquered the most part of the Ionian coast and Ionian hinterland of Illyria, including Bylis. Yet, two years later, a rebellion in nearby Apollonia and the intervention of Illyrian king Glaucias removed this Macedonian control. Glaucias’ successor Monunious placed his residence in the Byline city of Gurëzezë. During 284-282, Bylis fell under the control of Epirus state after its ruler Pyrrhus of Epirus defeated the armies of Monunios in a series of unknown wars. Pyrrhus’ successor Alexander held his father control for a while until the Illyrian king Mytilus re-established control over Bylis sometime after 270.

In about 270, the inhabitants of Bylis formed a clear distinctive league (koinon). It stretched beyond the city itself, covering a surface of roughly 20 sq.km. This area corresponds to the current region of Mallakastra along river Gjanica. Along with Bylis and Nicaea, the koinon included other settlements identified in Margellic, Gurëzezë , Kalivac, and Rabie. This political organization struck its own coins in bronze continuously until 167 when Romans dissolved it.

Urban and Political Organization

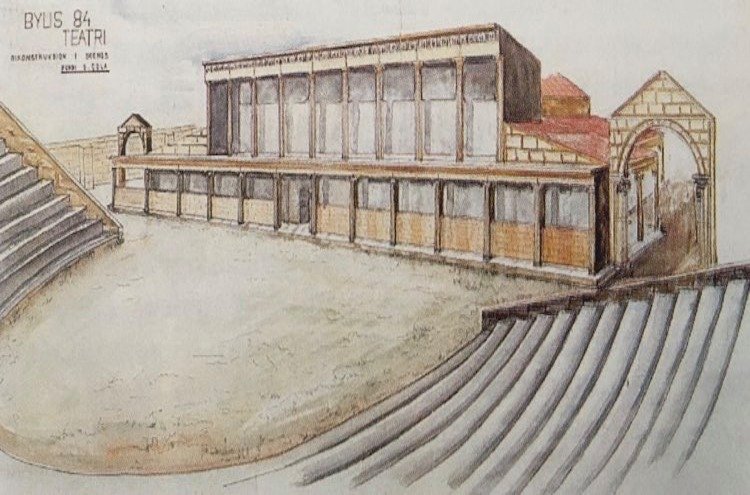

During this period, especially in the mid-III century B.C.E., the public square (agora) took shape. Public buildings such as the theater, stadium, gymnasium, and portico surrounded the agora, mostly consisting of horizontal blocks of hewn stone.

The urban quarters developed according to the Hippodamian plan. Bylis sealed its position as the main urban center of the League of the Byline with other leagues’ settlements mainly serving for its defense.

Epigraphic evidence reveals the political institutions that governed the koinon. Ecclesia/ekklesia represented the highest legislative body, composed of free citizens. Another body, the council of the demiourgoi serves as some kind of Senate consisting of representatives from all subtribes across the koinon. A prytanis (elected each year) exercised the highest executive authority. Next in line of authority was a commander of the infantry (strategos), and a commander of the cavalry (hyparchos).

Theatre of War

The year 229 marked the first landing of Roman conquerors in these parts as well as their first military engagement east of Adriatic. The territory of Bylis as well as the whole Atintania was among the first areas to be incorporated in whatever protectorate the Roman established in what corresponds to west-central Albania. Bylis and other Roman annexed territories were used as bases to fight the Illyrians of queen Teuta in the First Illyrian War (229-228) and against Demetrius of Pharos in the Second Illyrian War (219).

For some decades, Bylis turned into the battlefield between the Romans and Macedonians. In 213, Philip V conquered the city along with the region of Atintania. The latter intended to use the city as a springboard from where he could threaten the important city of Apollonia as well as other Roman possessions along the coast. In 198, the Romans eventually triumphed over the forces of Philip V not far from Bylis, in the narrows of Aoos near the current town of Tepelena. The victorious Romans awarded the city with its autonomy in exchange for Bylis’ allegiance.

The victory in the Aoos Stena did not settle Roman-Macedonian conflict. Another Roman-Macedonian War and Illyrian War took place during 179-168 in which contingents from Bylis took part alongside the Romans to fight the Illyrian ruler Gentius. However, other populations from the region of Atintania supported the anti-Roman coalition of the Molossians and Macedonians. The Roman consul Paul Emilus launched a punitive expedition against those who had supported the enemy, after he defeated the Macedonians. Yet, in the following destruction and carnage, the Romans generally spared the city of Bylis. While the Romans caused only limited damages to Bylis, they razed to the ground most nearby towns.

Reorganization

From the destruction of 167 to more than a century on, there are no written records on Bylis. As other settlements, this city suffered from the general depopulation of the region. According to archaeological evidence the populace abandoned completely the surrounding satellites of Bylis. However, the latter maintained its former glory. The citizens even rebuilt the destroyed part, apparently with Roman consent. Romans recognized the status of “koinon” (“community”) only to the city of Bylis. They also allowed the city to continue minting its own characteristic bronze coins but with a change in inscription from “Bylionon” (“coin of the Bylliones’) to “Byllis”, now under Roman control.

In 54 according to a letter of Cicero, the League of Bylis stands in a conflict with the Illyrian proconsul (L. Kuleolin). In 44 Cicero accuses Brutus before the Senate for invading Bylis, along with the nearby autonomous cities of Apollonia and Amantia. During the civil war between Caesar and Pompey, Bylis turned into Caesar’s side as soon as the Roman general conquered Apollonia. The citizens accepted a garrison of Caesar’s guards into their city.

Romanization

Strabo, the geographer of the Augustan era, seems to be the latest who mentions the koinon of the Bylliones under the name “Bylliake”. Apparently, Bylis turned into a Roman colony during the reign of Octavian Augustus. Several latin inscriptions discovered in its ruins support this view and refer to the settlement as Colonia Iulia Augusta. Pliny also refers to the city as a colony.

After gaining the status of the Roman colony, Bylis experienced a second wave of development. The surrounding walls were rebuilt along with the theater and stoa, while other monuments were founded. A colony of Roman veterans settled in Bylis as the city positioned strategically along the road that connected Apollonia with Epirus and Macedonia through the valley of Aoos (Vjosa) River.

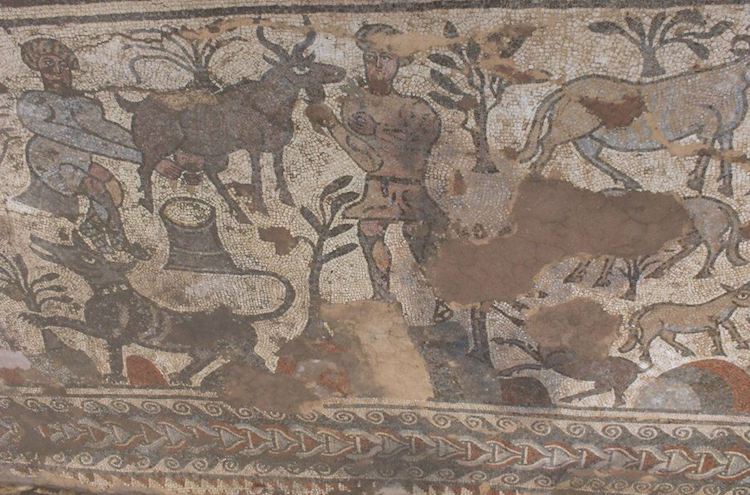

Ruins of rich houses paved with mosaics reflect the wealth of the new Roman citizens/colons, mostly Roman veterans. One of these veterans, Marcus Lolianus, who had served in various military provinces, financed the construction of a road that linked Bylis with Astacia (which apparently refers to nearby Nicaia). Along this road stood also a bridge over a river named “Argia” that may correspond to modern river Povla or Gjanica. Another Roman citizen of the Saleni family built with his own expenses a public bath that remains undiscovered.

Governance during Roman era

Through epigraphic evidence we gain a glimpse into the institutions that governed the new Roman colony of Bylis. The Colonial Senate (decurio) was the one the most important institutions. The most renowned citizens composed this legislative body. These individuals dealt with the most important affairs of the city.

The dummvirs (duumviri), two magistrates elected jointly each five years, held the executive power. An inscription reveals also two augustales who financed with their personal revenues festivities and sport races honoring the emperor.

The influx of Roman colons increased the economic importance of Bylis. The presence of Bylis in the II-nd century C.E. map of Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy reveals its importance. The colony turns into the region’s most important craft production community. It reflects the presence of workshop branches of crafting firms from northern Italy such as “Felix” and “Fortis”. These manufacturers produced items for exports as well as for local use.

In the I century C.E., other settlements rose into the territory that belonged once to the Bylis League, along the Aoos river valley. The most important of these settlements was the one formed in the Qesarat village where there were found traces of ancient houses with substantial surfaces, as well as sculptures and mosaics.

Late Antiquity

Bylis, as other cities along the Ionian coast, was destroyed almost completely by the assaults of the Vizigotes during 383-392, during the reign of Valentinian II. The destruction of the city radically shaped the old civic structure. The settlements began to serve as a safe haven for the rural population of the area as well as an alternative shelter to parts of the population that abandoned the nearby city of Apollonia.

Reconstruction initiatives were carried out in Bylis from the reign of Teodos II (408-450) onwards. The surrounding protective walls, torned down during Pax Romana, were rebuilt. These reconstructions did not follow the previous urban models of the city. A large number of churches were erected inside and outside the protective walls. During the first half of the VI-th century properties of church extended in the surrounding areas as locations of more than 20 old churches have been identified in this region.

Fall

Inscriptions of various contributors of religious buildings reveal to some extent the new identity gained by the city. Thus, a large cathedral rose up along with its episcopal complex. It covered an area similar to that covered by the old agora. The available evidence of that time reveals a high ranked official holding simultaneously the roles of the prefect (eparhikos) (prefect) and protector of the city (ekdikos). This office seems to reveal a temporary position in response emergent threats such as invasions. Pottery production continued to thrive even in these unstable times.

Another wave of barbarian invasion caused destruction in the city during 547-551. Authorities reconstructed the city but only into one third of its original surface. However, the reconstructions could not prevent Bylis eventual decline in the second half of the VI-th century. In 586, the Slavs sacked Bylis making it uninhabitable for next generations. As such, the episcopal center moved into the nearby city of Ballsh (inheriting Bylis’ toponym). A Christian basilica was already present here since the mid-VI century.

Bibliography

Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Instituti i Arkeologjisë. (2002). Ilirët dhe Iliria te Autorët Antikë. Botimet TOENA, Tiranë.

Ceka, N. (1990). Fortifikimet Antike të Bashkësisë Byline. Iliria. Nr. I.

Gloyer, G. (2008). Albania. The Bradt Travel Guide. The Globe Pequot Press Inc.

Muçaj, S & Ceka, N. (2004). Bylisi. ILAR, Tiranë.

Prence, D. (2013). Bylisi si Qendër e Rëndësishme Turistike. Universiteti “Aleksandër Moisiu” Durrës. Fakulteti i Shkencave Politike Juridike. Durrës.

No references?

Thank you for the comment and interest. This article was largely based on the following works (kindly accept them as the references of this article):

Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Instituti i Arkeologjisë. (2002). Ilirët dhe Iliria te Autorët Antikë. Botimet TOENA, Tiranë.

Ceka, N. (1990). Fortifikimet Antike të Bashkësisë Byline. Iliria. Nr. I.

Muçaj, S & Ceka, N. (2004). Bylisi. ILAR, Tiranë.