Epirus during Alexander the Molossian rule

Despite the intervention of Philip, the reign among the Molossians remained within the same royal family, known as the Aeacides family. However, Alexander, coming from the Macedonian court, would be a natural ally of Macedon. We can link the accession of Alexander in Epirus in about 350 B.C.E., with the establishment of a new constitution among the Molossians and other tribes in Epirus. It seems that it is during his reign when Epirus, apart from its geographical meaning, gained a political designation as well. The rather loose alliance of Epirot tribes that originated since the time of Alcetas was now formally turned into an alliance or “symachy” of the Epirotes.

In the context of regional developments, this Epirot Alliance was a political organisation similar to what Philip established at Corinth. By apparently influencing the “symachy”, the Epirotes, had their own alliance without having to become an unnatural part of the pan-hellenic League at Corinth. Epirus was regarded as a region with a low or uncertain degree of Hellenism, traditionally non-participant in Greek alliances, so there could not be a seat for them in the Corinthian League. Rather, Epirus would continue to have its own king that would rule over a distinct symachy. The “Epirot constitution” of Aristotle, it seems, refers to this constitution first organised in the reign of Alexander in imitation of Philip’s settlement at Corinth.

The newly established federal state did not remove the local autonomy and governance of its constituent tribes. The founding members of this Alliance seem to have been the Thesprotian League, the Cassopaeans, and, of course, the Molossian League. The Chaonian League would join after Alexander’s reign the Alliance, sometime during 325 – 320 B.C.E. As the Greek cities further south participants in the Corinthian League, each Epirot tribe or tribal league continued to have its own assembly and maintain a significant degree of local autonomy. However, each tribe had to send its own delegates each year at Dodona, who, as a popular and common sanctuary among the Epirotes, turned into an ideal federal capital for the Alliance. As stated by Geoffrey Neale Cross, the yearly meeting of the Alliance at Dodona was:

“presided over by the “prostates” of the Molossians, who combined this function with his presidency of the Molossian tribal assembly. Alexander’s kingship, too, was still limited to his own tribe – he is always “the Molossian” and not “the Epirot”- but he was – if one may borrow an expression from Corinth, “hegemon” of the Epirot confederacy and destined to lead it – as Philip hoped to lead the Greeks – on an expedition in the cause of hellenism”.

While Asia Minor had been projected by Philip as the common enemy of Macedon and the Corinthian League, the “symmachy” of the Epirots faced not much different foreign layout on the west. The so-called empire of Dionysius of Syracuse had turned into a relic and fighting had broken out for its pieces. It was this situation that made Plato concerned for the Hellenic Civilisation in the west.

After the peace of Philocrates in 346 , Philip would turn his attention towards the regions of Epirus. He further strengthened border security by annexing in 344 the regions of Orestis, Parauaea, and apparently Tymphaea as well. These areas would be incorporated into his Macedonian kingdom rather than into the Epirot Alliance. However, Philip would return the favor to Alexander a year later.

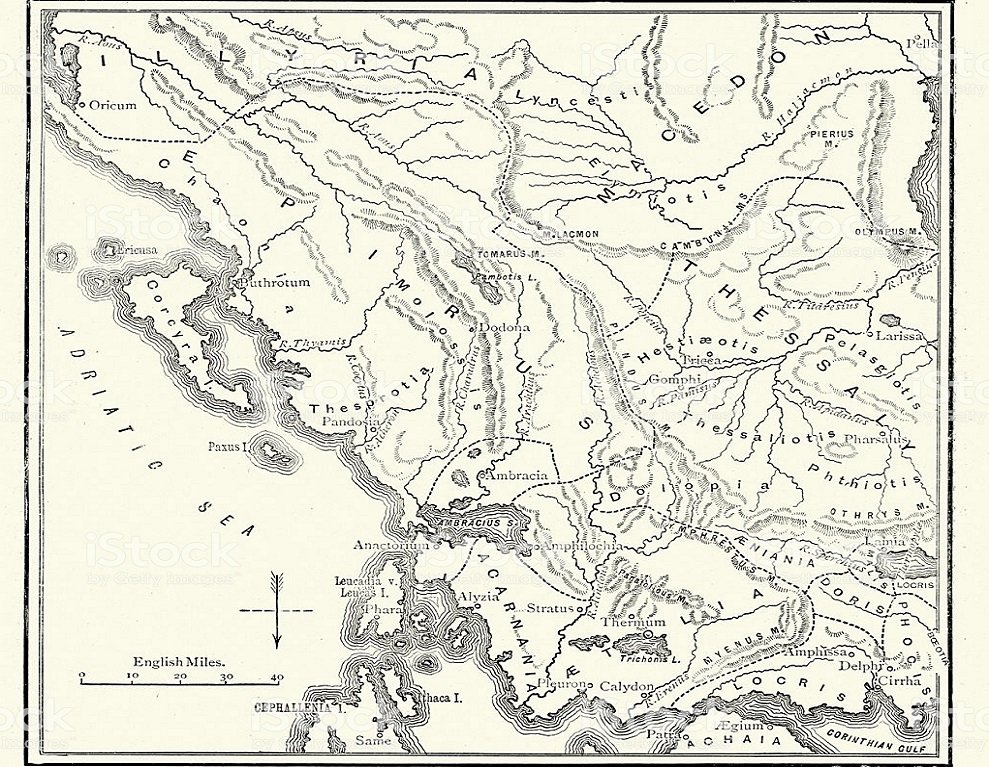

In 343 B.C.E., Philip took an operation across the southern Epirus, in what appears to be a well-coordinated expedition with Alexander the Molossian. It is worth noting that before moving into southern Epirus, Philip had sent Athens several peace proposals in what seems to be an effort of the Macedonian to appear as a reasonable and fair leader. The Athenians were still discussing the peace terms proposed when the Macedonian forces, starting from Pella, crossed into the territory of the Molossians through the inland route Brucida north of Lake Brygeis (Prespa) – Pelium near river Eordius – Omphalium. It seems that the safety of the Philips’ troops during march through Epirus was guaranteed by Alexander the Molossian himself. The latter was interested in a successful expedition of the Macedonians as the Molossian expected to be awarded with territorial gains that would compensate the easternmost Epirot regions left under Philip’s influence a year before.

The main targets were the regions of Cassopia and Ambracia. The Cassopaeans and the Ambraciotes controlled important trading stations along the Ambracian Gulf and had and thus held a monopoly over the trade between Ambracia and Corinth. In Cassopia, Philip assaulted three colonial avantposts of the Eleians, Pandosia, Boucheta, and Elatea. After reducing them, he surrendered their territories to Alexander. Along with these cities, the Epirot Alliance earned a strip of land that went along the Ambracian Gulf, from the beginning of it at the Ionian Sea into near-Ambracia region.

This expedition did not take long, and by early summer of 342 B.C.E. Philip moved south against the Corinthian colonies of Leucas and Ambracia. These colonies were major commercial hubs and the main exporters of Epirote timber and animal products to Corinth. The colonies, threatened by Philip’s troops, appealed for military help to Corinth, which in turn appealed to Athens. The Athenians responded promptly by sending troops to reinforce the neighbouring region of Acarnania while Corinthian troops reinforced the city of Ambracia. With the appearance of these reinforcements in the field, Philip decided to withdraw in order not to risk a direct confrontation with Athens for a non essential dispute.

Philips’ intervention made Alexander Molossus the first ruler from Epirus to rule a land significantly larger than others ruled by his predecessors. Alexander Molossus not only could influence the politics of the symachoi of the Thesprotians and Cassopeians through the political institution of the Epirot Alliance but also controlled the largest access to sea that the Molossians had achieved.

The relations between Alexander and Philip of Macedon take a step back in 337 B.C.E., when Olympias was repudiated by Philip and virtually expelled back into Epirus while her son Alexander went into Illyria. Olympias’ son succession was being threatened by the new marriage of Philip with Cleopatra\Eurydice, niece of Attalus, an important Macedonian noble. At her brothers court in Epirus, Olympias seem to have encouraged Alexander to enter into a war against Philip. The Molossian king must have been wisely hesitant to accommodate such a request, yet, even the thought of this idea playing out in Epirus must have worried Philip.

In early 336, Cleopatra/Eurydice gave birth to a daughter, who, as female, could not threaten Alexander’s the Macedonian position as heir. Thus, it must have been after this that Alexander, son of Olympias was asked to return into the Macedonian court. At the same time, Philip thought to neutralize the plottings of Olympias in Epirus by offering to Alexander the Molossian his daughter Cleopatra in marriage. The new marriage and Alexander the Molossian’s acceptance of Cleopatra as a wife would reaffirm the alliance between Macedon and Epirus. The bride was the daughter that Philip had with Olympias, making her at the same time the niece of Alexander the Molossian, her new husband. Yet, the practice of marrying a niece was not unusual among the Epirotes or among other populations in antiquity.

The marital celebrations were planned to be held during the summer of 336 B.C.E. at Aegae/Aigai, the old royal capital of the Macedonians. At the celebrations at Aegae, Philip was assassinated by Pausanias who had an old grievance against Attalus and, as a result, against Philip himself. The assassination of Philip must have been an important event for the parties involved but that same event paved the way for Alexander the Macedon to become Alexande the great.

As for Alexander of Epirus, after the assassination at Aegae, he went back into Epirus, taking with him his new wife Cleopatra. The new bride gave birth in Epirus to Alexander’s childs, princess Cadmeia and their son Neoptolemus II. With the royal line and domestic position secured, Alexander the Molossian could aim to achieve higher ambitions. The plans seem to have been already laid out, in continuation with those initiated by Philip.

Traditional narrative suggests that by 334 B.C.E. Alexander the Molossian received an appeal from Taras to help them against the Italic tribes threatening its position. This was not the first time a foreign entity was invited to campaign in southern Italy. Accordingly, in between 343 and 338 B.C.E., king Archidamus III of Sparta had campaigned in southern Italy with mixed success. Also, in between 344 – 337 B.C.E., the Corinthian Timoleon freed Syracuse in a series of wars against the Carthaginian threat. What makes this case different is that this marks the first time an appeal is sent to Epirus, a state outside mainland Hellas and seemingly not in a position to launch an expedition outside its own borders. A more plausible theory suggests that the appeal was actually sent to the Corinthian League sometime before Philip was murdered. The appeal was thus received by Philip as the hegemon of the Corinthian League. As the Macedonian king was planning an invasion of Asia Minor, he must have delivered that appeal to his ally Alexander of Epirus, even encouraging him to respond to that invitation.

The accession of the new king Alexander into the Macedonian throne, did not change the relations between Macedon and Epirus and their respective political aims. Macedon continued to act as an important player in Epirot affairs. Both rulers carried forward their roles as protectors of Hellenism and, on such pretext, embarked on imperial ambitions. Alexander of Macedon would commit to accomplishing his father’s goal of subduing Persia while the other Alexander of Epirus would launch another expedition of the same nature in the west. In such context, it may have been no coincidence that both Alexanders launched their respective offensives into foreign lands at the same time, the Macedoanin crossing into Asia Minor while the Epirot crossing into southern Italic peninsula.

In 334 B.C.E. Alexander the Molossian crossed the sea with a small force of fifteen vessels but many other trading ships. The size of his army must have been relatively small, and mainly in the form of cavalry units. In terms of infantry, Alexander relied mostly from troops he found in Italy such as units from Tarentum, or exiled soldiers from the native tribes, as were the two hundred exiled Lucanians he incorporated into his force. Although the Epirot had witnessed the effectiveness of the phalanx formation applied by Philip, his infantry, made up by a composition of different people, must have continued to follow the traditional hoplite fighting. What he could have adapted more easily was the increased mobility of the cavalry in the battlefield.

While Alexander was campaigning outside Epirus, his wife Cleopatra took over the domestic governance. The high status women enjoyed in Epirus favored her in taking such position, not to mention her strong character similar to her mothers. Meanwhile her mother Olympias has taken charge of the affairs in Macedon in the absence of her son Alexander the great. In 334 – 333 B.C.E., the name of Cleopatra of Epirus is recorded in a theorodokoi list from Argos as the “welcomer of sacred ambassadors” (“theorodokoi”) who would travel to various regions to announce the Nemeian festival. Cleopatra is the only female in that list and the presence of her name further supports the claim that she was the regent ruler of Epirot Alliance in the absence of her husband. To be noted is also the close relation that Cleopatra maintained with her full-brother Alexander of Macedon, a relation that the latter did not harness with his other half-sisters. We can even assume that Alexander the Great, through the figure of his sister, established in Epirus his direct influence. In 332 B.C.E., after the siege of Gaza, Alexander the Macedonian sent large quantities of booty to his mother in Macedonia as well as to his sister in Epirus.

Meanwhile in Italy, Alexander achieved an important victory against the Lucanians near the Lucanian shore, at the Hellenic city of Paestum otherwise called Posidonia. This victory echoed in the whole of Italy. The Romans, then in their eighteen year of war against the Samnites, sent congratulatory embassies to Alexander and signed some sort of alliance with him. The victory was followed by other successes. Alexander recaptured from the Lucanians the city of Heraclea, a colony of Tarentum, as well as Terina, a colony of Crotona, from the Brutti. His troops conquered the regions of Messapia and Lucania, capturing and subduing many people in the process. Tarentum perceived these victories as invasive and withdrew its support to him. Alexander advance eventually concentrated in Pandosia, a Hellenic city of strategic importance, located at an imaginary borderline between the realms of Lucanians and Brutii. The Epirot plan was to turn this city into a base from where he could easily launch offensives against either the Lucanians or the Brutii.

In the beginning of 331 B.C.E., during the operations for the control of Pandosia, the events turned against the Epirot king, the enemy assaulting his troops while they were divided and slow because of flooded terrain. The king himself was killed by the Lucanians exiles he had included in his ranks while pushing his troops through a bridge. It was the time when a city named Alexandria was founded in Egypt by his namesake of Macedonia.

Notes:

This article continues from https://albanopedia.com/ancient-states-regions/epirus-before-the-reign-of-alexander-the-molossian.

This article continues in: https://albanopedia.com/ancient-states-regions/epirus-before-pyrrhus